If you take a teaspoon and dip it into the ocean what will you have? Some drops of lifeless water? Only a few decades ago this is what scientists would have said, however, the development of increasingly powerful microscopes have shown us a world long unknown, which has vital importance for the survival of one of the world’s most threatened and most treasured ecosystems: coral reefs. A single milliliter of water is now known to contain at least a million living microbes, i.e. organisms too small to see without a microscope. After discovering their super-abundant presence, researchers are now beginning to uncover how these incredibly tiny life-forms shape the fate of the world’s coral reefs.

“Microbes are intimately associated with the coral animal where, for example, they contribute by recycling nutrients. This is especially vital work for a healthy reef because nutrients such as usable nitrogen are scarce and often limit growth,” explains Dr. Forest Rohwer, creator and head of the Rohwer lab at San Diego State University. In addition, Rohwer has recently co-written a book on coral reefs for the general reader entitled, Coral Reefs in the Microbial Seas, which has received overwhelmingly positive reviews on Amazon.com.

Dr. Forest Rohwer in the Line Islands. Photo courtesy of: Forest Rohwer. |

In a recent interview with mongabay.com, Rohwer explained that while microbes are vital to reef survival, they can also lead to coral decline and death, especially when impacted by ocean degradation through overfishing or nutrient pollution from sewage and agriculture.

“On the negative side, having too many microbes kills corals. Many human activities favor the ‘microbialization’ of the coral reef. Having all of those extra microbes eventually overwhelms the coral’s defenses and the corals die,” Rohwer says, adding that “in many ways it is simply a numbers game. There are more microbes than anything else and they are getting the lion’s share of nutrients and energy. Any human activities or environmental shifts that increase the microbial numbers or favor one type over another will affect who on the reefs gets the nutrients and the energy, who will thrive and who will die.”

The increasing understanding of the role microbes play in the fate of coral reefs has already had political impact says Rohwer.

“Microbial data from our studies was one factors prompting President Bush’s administration to dramatically enlarge America’s marine protected areas […] Policy makers who want to protect the reefs need to know which factors are most important for reef health. Thus, studies such as ours that link overfishing and microbes to coral death can enable them to take the actions that will be most effective.”

Despite being one of the world’s most imperiled ecosystems, Rohwer is generally optimistic about the coral reefs long term survival. In addition to many devoted conservationists and scientists working on saving reefs, Rohwer points out that corals survived 200 million years of environmental shifts before humans came along. Still, saving coral reefs will require major societal changes both on land and in the sea.

Front cover of Forest Rohwer’s new book. Photo courtesy of: Plaid Press. |

“Stopping [overfishing and nutrient pollution] will require the economic clout to enforce regulations for responsible fishing, improve local sewage treatment, and promote agricultural practices that keep the fertilizer on the land. These actions will also improve the health and the resilience of the reefs, making them better able to cope with the environmental challenges that lie ahead,” he says.

Rohwer adds that while coral reefs provide a number of ecosystem services, such as important fishing grounds and tourism, their beauty alone should be enough to push societies to make the hard decisions necessary to save them from destruction.

“Beauty is incredibly valuable. The Louvre is something that we all agree should be preserved, and if you would dare mess with Yellowstone Park essentially everyone would be up in arms. Coral reefs also qualify here. Just ask anyone who has ever had the opportunity to enter this lively underwater realm.”

In an August 2010 interview with mongabay.com Forest Rohwer spoke about the connection between coral reefs and the oceans’ microbes, the importance of sharks to reefs, his new book, and his hopes for the world’s stunning coral reefs.

INTERVIEW WITH FOREST ROHWER

Mongabay: What’s your background?

Forest Rohwer taking samples in the Line Islands. Photo by: Zafer Kizilkaya. |

Forest Rohwer: I grew up in Idaho on a cattle ranch. My dad being an animal nutritionist and my mother running the Bar Diamond analytical lab meant that I’ve always been around scientists.

After high school, I went to the College of Idaho for my BA with emphasis in history, biology, and chemistry. Then I spent a year at the University of Idaho trying to learn Latin and working in a molecular biology lab. I realized that I’d rather do something new than study what other people had done, so I transferred to the joint doctoral program in molecular biology at San Diego State University and UC San Diego. There I studied how Human T-cell Leukemia Virus-1 (HTLV-1) and Interleukin-2 (IL-2) controlled the cell cycle in T cells.

As I was finishing my PhD, I heard a talk by Farooq Azam, an outstanding marine microbiologist at the nearby Scripps Institution of Oceanography (SIO). That was the first time I heard about the multitude of viruses in the world’s oceans. That was exciting! New Ph.D. in hand, I moved to SIO where I studied marine viruses and coral associated microbes with Farooq and coral reef biologist Nancy Knowlton. In 2002 I returned to SDSU as a faculty member and set up my own lab to continue this research.

Mongabay: How did you first become interested in coral reefs?

Forest Rohwer: While an undergraduate, I went on a life changing field trip to Australia and the Great Barrier Reef. I loved it. Later, while at SIO and studying marine viruses, I realized that this type of research called for being able to sample the “same” place repeatedly, which is hard to do in the open ocean. The mucus surface on corals with its teeming microbial community seemed like a great place to start.

Mongabay: You recently wrote a book: Coral Reefs in Microbial Seas. Why did you choose to write it for a general (non-scientist) audience?

Forest Rohwer: People who are interested in coral reefs span the gamut from divers and fishermen to resource managers to scientists in many fields, and all of these people are important for the future of coral reefs. There is a fascinating story emerging linking the sharks and the microbes to the health of a coral reef ecosystem, but there had been no single source that pulled together all the pieces. I wanted to make this whole picture easily available to a broad audience. Even many coral reef scientists need to know about the findings recounted in the book.

MICROBES, SHARKS, AND CORAL REEFS

Mongabay: What is a microbe? What importance do they play in the ocean?

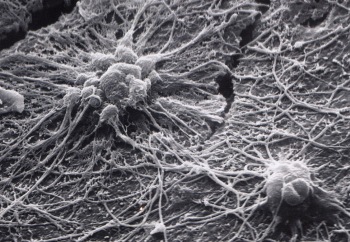

Technology has allowed researchers to see what no one has seen before. This is an Electron Microscopy image of bacteria on a reef. Photo courtesy of: Forest Rohwer. |

Forest Rohwer: “Microbe” often refers to any living organism that is too small to be seen with the naked eye, but I use the term in the book to specifically refer to large two groups of microscopic, single-celled organisms—the Bacteria and the Archaea. Because they are exceedingly abundant, grow quickly, and carry out diverse metabolic processes, microbes control the flow of energy and nutrients in the world’s oceans.

Mongabay: Studies of microbiology are relatively recent. Why were the ignored for so long?

Forest Rohwer: Early studies in microbiology were focused on those types of microbes that could be grown by themselves in the lab, especially those that were useful for food production or that caused disease. We didn’t yet have techniques for studying the diverse microbial communities found in natural environments; we couldn’t even count them until the needed microscopy techniques were invented in the mid-1970s. Only then did we realize that there are a million microbes and ten million viruses in every milliliter of seawater. Soon thereafter, scientists started to consider microbes as an important part of the marine world. In the early 1980s, when a number of investigators developed methods to measure microbial activity in seawater, they found that microbes accounted for more that half of the flow of carbon in the oceans, both the capture of CO2 by photosynthesis and its release by respiration. Soon thereafter breakthroughs in DNA sequencing and analysis revealed that the microbes and viruses are the most diverse organisms in the oceans. And it wasn’t until we were a few years into the 21st century that we could routinely determine what those marine microbes were doing metabolically.

Mongabay: What role do microbes play in coral reefs?

Corals known as Porites furcata. Photo courtesy of: Forest Rohwer. |

Forest Rohwer: On the positive side, microbes are intimately associated with the coral animal where, for example, they contribute by recycling nutrients. This is especially vital work for a healthy reef because nutrients such as usable nitrogen are scarce and often limit growth. On the negative side, having too many microbes kills corals. Many human activities favor the “microbialization” of the coral reef. Having all of those extra microbes eventually overwhelms the coral’s defenses and the corals die.

Mongabay: Why do you call microbes the ‘key’ to coral reef life and death?

Forest Rohwer: In many ways it is simply a numbers game. There are more microbes than anything else and they are getting the lion’s share of nutrients and energy. Any human activities or environmental shifts that increase the microbial numbers or favor one type over another will affect who on the reefs gets the nutrients and the energy, who will thrive and who will die. Of course, some specific microbes can cause specific diseases, just as with humans, but the numbers game sets the stage by increasing susceptibility to disease.

Mongabay: Could recent understanding of the microbe’s role in coral reefs help us protect them?

Forest Rohwer: It is already happening. Microbial data from our studies was one factors prompting President Bush’s administration to dramatically enlarge America’s marine protected areas, including some of the Line Islands where we have done much of our research. Policy makers who want to protect the reefs need to know which factors are most important for reef health. Thus, studies such as ours that link overfishing and microbes to coral death can enable them to take the actions that will be most effective.

Mongabay: In the book you write that if there are no sharks there are no coral reefs. Why?

Forest Rohwer: A pristine coral reef has lots and lots of sharks. If people fish them out, the whole coral reef ecosystem flips to a different state that favors the microbes. Essentially, what is going on is that the sharks eat vast numbers of the smaller herbivorous fish. These small fish in turn feed on the algae, keeping the algae well grazed. To replenish those little fish requires a huge amount of algae. Thus the more sharks, the more algae that is consumed and transformed into small fish and ultimately into shark biomass. If you remove the sharks, the herbivorous fish don’t have to reproduce as much; we all know it takes more food to grow kids than to maintain adults. So the algae grows larger. For algae, picture large, tough seaweeds. The algae release sugars into the water that feed the microbes. More algae feed more microbes. More microbes, especially the wrong kinds of microbes, kill the corals. Thus no sharks, no corals.

Mongabay: What other species are needed for coral reefs to survive?

Along with sharks, sea urchins, such as this one, play an important role in coral survival. Photo courtesy of: Forest Rohwer. |

Forest Rohwer: The reef-building corals are considered keystone organisms on coral reefs. Remove the keystone, and the ecosystem collapses. Many, many other organisms are also necessary, some of which help to build the reef structure. There is a great deal of redundancy in the reef community, with more than one species able to carry out each needed job. So in that sense, many individual species aren’t needed, so long as there is another one still present that is able to do the same job. By 1980 many of the algae-grazing fish had been removed from the Jamaican reefs and the reefs still looked healthy with lots of corals, thus suggesting that those fish weren’t needed. Sea urchins that also eat the algae were super abundant. But then, in 1983, an epidemic struck, quickly killing almost all of the sea urchins. Without either enough fish or enough sea urchins to graze the algae, the reef ecosystem collapsed into an algal-dominated slime.

Mongabay: How does the idea of ‘shifting baselines’ affect coral reef science?

Forest Rohwer: Each generation of scientists regards the state of the reefs when they first visited them as “normal.” By the time the next generation arrives on the scene, the reefs have degraded farther, but again the current state is taken as the norm, the standard for comparison. Thus over the years our baseline for coral reef studies has shifted so that now most of us don’t even know what a truly pristine coral reef looks like. One important example of this concerns how many sharks and top predators there should be on a coral reef. Until recently, coral reef scientists didn’t realize that there should be lots and lots of sharks, that most of the fish biomass on a reef should be in the form of sharks and other big predators.

THE END OF CORALS?

Mongabay: Coral reefs may be one of the most threatened ecosystems in the world. Why?

Where a reef used to be: an anchor rests in Bocas del Toro, Panama where once stood large stands of coral reefs that have been decimated in the past few decades. Photo by: Neilan Kuntz of Plaid Multimedia. |

Forest Rohwer: That’s a particularly good question, given that coral reefs have survived for more than two million years and are quite resilient. Coral reefs today are being stressed from several directions at once. Overfishing has accelerated, encouraged post WWII by the development of high tech fishing. Likewise more reefs are dealing with nutrient addition. Large-scale coral bleaching in response to warmer water, unheard of before the 1980s, has become frequent in many regions. New pathogens continue to be reported on these stressed reefs. And all of these changes are occurring very rapidly.

Mongabay: What would you characterize as the biggest threats to the world’s corals?

Forest Rohwer: Right now those would be overfishing and pollution. By pollution, I am referring to human activities that result in increased nutrients in the reef waters. This can be the result of sewage discharge, run-off of excess fertilizer from nearby land, nutrients released from aquaculture pens, among others. Both overfishing and pollution stress coral reefs and make them more susceptible to the global changes underway—the increasing sea surface temperature and ocean acidity.

Mongabay: How do we save the world’s coral reefs?

Forest Rohwer: Stop killing the coral reefs. In many places we’ve already halted the most blatantly destructive activities such as dynamite fishing, so now the primary culprits are overfishing and nutrient addition. Stopping these will require the economic clout to enforce regulations for responsible fishing, improve local sewage treatment, and promote agricultural practices that keep the fertilizer on the land. These actions will also improve the health and the resilience of the reefs, making them better able to cope with the environmental challenges that lie ahead. Those reefs that we predict will have the best chance of surviving those long-term changes should be completely protected now.

Mongabay: Given the number and size of threats, and, at least to date, little political will, how optimistic are you that coral reefs will survive?

Forest Rohwer: I am fairly optimistic for two reasons. The first is the many people working hard to protect coral reefs around the world. More people now realize that short-term exploitation robs them or their community. They see that coral reefs are much more valuable when maintained as long-term resources. I’m counting on this sort of enlightened self-interest, combined with greater understanding about how coral reefs work, to lead to sound reef management. The second is the coral holobiont, this being the coral animal with its many symbiotic partners. Together they have weathered over 200 million years of environmental change. Together they are adaptable and resilient.

Mongabay: What would an ocean without coral reefs look like?

White pox disease on a palmata coral. Photo courtesy of: Forest Rohwer. |

Forest Rohwer: About the same. Worldwide, coral reefs cover less than 1% of the ocean floor. It’s important for people to realize that the oceans are essentially a vast microbial soup. If we lose the reefs, we will still have the soup, but we will have removed the beautiful large things that everyone, from kids to grandparents, loves. I am a microbiologist, but I go swimming in the ocean to see all the beautiful fish, corals, and other bizarre life forms. If we loss the reefs, then instead of experiencing some of the most aesthetically pleasing places on the planet, we’ll be left with only algae and microbial slime.

Mongabay: Beyond their beauty, why do we need coral reefs?

Forest Rohwer: I am not sure that we need to justify them beyond this. Beauty is incredibly valuable. The Louvre is something that we all agree should be preserved, and if you would dare mess with Yellowstone Park essentially everyone would be up in arms. Coral reefs also qualify here. Just ask anyone who has ever had the opportunity to enter this lively underwater realm. If you want other reasons, it is clear that reefs provide valuable services for humans. What comes to mind first is that without coral reefs, many people would have many fewer fish to eat. Millions of people rely directly on the reefs for their livelihood, and many more benefit indirectly from the reefs in the form of protein-rich seafoods, coastline protection, and other services measurable in dollars.

Mongabay: If you could pick one person in the world to read your new book, who would it be and why?

Forest Rohwer: Bill Gates. He has put an amazing amount of money into helping alleviate poverty in developing nations. However, his approach has been somewhat one-sided. We need to put as much effort into fostering sustainable usage of the environment as into curing malaria.

The coral pictured here, Acropora palmata, is one of the most important framework builder species of coral reefs in the Caribbean. Photo taken in Bocas del Toro, Panama. Photo by: Neilan Kuntz of Plaid Multimedia.

Related articles

Massive coral bleaching in Indonesia

(08/16/2010) A large-scale bleaching event due to high ocean temperatures appears to be underway off the coast of Sumatra, an Indonesian island, reports the Wildlife Conservation Society (WCS).

The biology and conservation of declining coral reefs, an interview with Kristian Teleki

(08/15/2010) Coral reefs are often considered the “rainforests of the sea” because of their amazing biodiversity. In fact, coral reefs are one of the most diverse ecosystems on earth. It is not unusual for a reef to have several hundred species of snails, sixty species of corals, and several hundred species of fish. While they comprise under 1% of the world’s ocean surface, one-quarter of all marine species call coral reefs their home. Fish, mollusks, sea stars, sea urchins, and more depend on this important ecosystem, and humans do too. Coral reefs supply important goods and services–from shoreline protection to tourism and fisheries–which by some estimates are worth $375 billion a year.

Coral reefs doomed by climate change

(07/22/2010) The world’s coral reefs are in great danger from dual threats of rising temperatures and ocean acidification, Charlie Veron, Former Chief Scientist of the Australian Institute of Marine Science, told scientists attending the Association for Tropical Biology and Conservation meeting in Sanur, Bali. Tracing the geological history of coral reefs over hundreds of millions of years, Veron said reefs lead a boom-and-bust existence, which appears to be correlated with atmospheric carbon dioxide levels. With CO2 emissions rising sharply from human activities, reefs—which are home to perhaps a quarter of marine species and provide critical protection for coastlines—are poised for a ‘bust’ on a scale unlike anything seen in tens of millions of years.

Amazing reefs: how corals ‘hear’, an interview with Steve Simpson

(07/21/2010) Corals aggregate to form vast reefs, which are home to numerous species and provide vital ecological services such as protecting shorelines. However, coral reefs are one of the most threatened ecosystems in the world due to many factors, such as global warming and ocean acidification. Recent research by Simpson and his team of scientists has shown that corals, rather than drifting aimlessly after being released by their parent colonies and by chance landing back on reefs, instead find their way purposefully to reefs by detecting the sound of snapping shrimps and grunting fish on the reef. However, that discovery also means that the larvae might struggle to find reefs when human noises, like drilling or boats, mask the natural ocean sounds.

World failing on every environmental issue: an op-ed for Earth Day

(04/22/2010) The biodiversity crisis, the climate crisis, the deforestation crisis: we are living in an age when environmental issues have moved from regional problems to global ones. A generation or two before ours and one might speak of saving the beauty of Northern California; conserving a single species—say the white rhino—from extinction; or preserving an ecological region like the Amazon. That was a different age. Today we speak of preserving world biodiversity, of saving the ‘lungs of the planet’, of mitigating global climate change. No longer are humans over-reaching in just one region, but we are overreaching the whole planet, stretching ecological systems to a breaking point. While we are aware of the issues that threaten the well-being of life on this planet, including our own, how are we progressing on solutions?

CITES rejects monitoring of coral trade

(03/21/2010) After denying protection to polar bears, sharks, and the Critically Endangered Atlantic bluefin tuna, the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES) has today voted against additional protections for harvested coral species, according to TRAFFIC, a wildlife trade monitoring group. The joint US and EU measure would have put in place scientific and trade monitoring of over thirty species of red and pink coral in the Mediterranean and western Pacific.

Healthy coral reefs produce clouds and precipitation

(03/03/2010) Twenty years of research has led Dr. Graham Jones of Australia’s Southern Cross University to discover a startling connection between coral reefs and coastal precipitation. According to Jones, a substance produced by thriving coral reefs seed clouds leading to precipitation in a long-standing natural process that is coming under threat due to climate change.

World of Avatar: in real life

(01/13/2010) A number of media outlets are reporting a new type of depression: you could call it the Avatar blues. Some people seeing the new blockbuster film report becoming depressed afterwards because the world of Avatar, sporting six-legged creatures, flying lizards, and glowing organisms, is not real. Yet, to director James Cameron’s credit, the alien world of Pandora is based on our own biological paradise—Earth. The wonders of Avatar are all around us, you just have to know where to look.

If protected coral reefs can recover from global warming damage

(01/10/2010) A study in the Caribbean has found that coral reefs can recover from global warming impacts, such as coral bleaching, if protected from fishing. Marine biologists have long been worried that coral reefs affected by climate change may be beyond recovery, however the new study published in PLoS ONE shows that alleviating another threat, overfishing, may allow coral reefs to cope with climate change.