As I discovered in the course of researching my book, No Rain in the Amazon: How South America’s Climate Change Affects the Entire Planet (Palgrave, 2010), the oil industry has had a poor record when it comes to protecting aquatic sea life. Take for example the manatee, which has been put at risk from the Amazon to the Gulf of Mexico as a result of the oil industry. One of the most outlandish creatures on the planet, the shy and retiring manatee, which gets its name from an American Indian word meaning “Lady of the Water,” was first described as a cross between a seal and hippo. The creature has a wonderfully round body, mostly black skin the texture of vinyl, a bright pink belly, a diamond-shaped tail and a cleft lip.

In the wake of BP’s disaster, the manatee could be in for a rough patch. Indeed, oil could ultimately result in death or significant injury in the event that manatees are exposed to petroleum. The docile sea creature, which can be found along the coasts of Louisiana, Mississippi, Alabama, and Florida, could ingest oil-damaged sea grass beds and other vegetation. Because manatees need to surface to breathe air, they could become exposed to oil on the water. If they ingest oil, manatees could develop lesions and erosions of the esophagus, liver toxicity and kidney problems. Ingestion could kill the organisms in manatees’ stomachs which aid in the digestion of sea grasses consumed by the animals.

A group of three West Indian manatees (Trichechus manatus) was photographed while feeding on seagrass. The West Indian manatee is native to the Gulf of Mexico. Photo by: US Geological Survey. |

Though the case of the manatee is certainly tragic, could we be missing the larger marine picture? For sure, surface petroleum provides easy photo ops and for weeks we’ve been subjected to countless images of oil washing up on local beaches. What’s been sorely lacking in the coverage, however, is any discussion of mysterious and inaccessible deep sea marine life. Take, for example, the enigmatic giant squid which will be placed at risk by BP’s methane emissions.

As it turns out, crude which is destroying the Gulf of Mexico contains about 40 percent methane which may suffocate marine life and create vast “dead zones” where oxygen becomes so depleted that nothing is allowed to live. Methane is a colorless, odorless and flammable substance which forms a major component in natural gas. It is used to heat people’s homes, and gets burnt off from crude before oil is shipped to the refinery. Though BP has sought to do just that as it captures crude from its breached well, some of the gas has escaped containment efforts and has wound up in the water.

When it is released into the ocean-atmosphere system, methane reacts with oxygen to form carbon dioxide. This in turn may result in something called marine dysoxia, a phenomenon which kills off oxygen-using animals. As small microbes living in the sea feed on oil and natural gas, they consume large amounts of oxygen which they require in order to digest food. That in turn exerts an unfortunate ripple effect: when oxygen levels decrease, the breakdown of oil can’t advance any further. What’s more, most life cannot survive under such conditions.

Residing in deep Gulf waters, the giant squid will be severely disrupted by lower oxygen levels. That is a pity, since we are only now acquiring basic information about the animal.

A young sperm whale. Photo by: NOAA. |

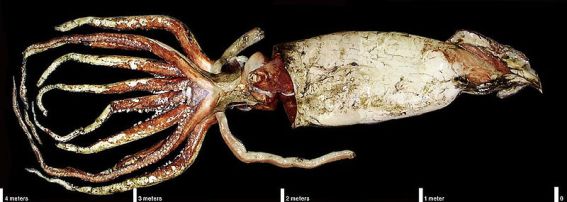

A creature which has inspired countless sea monster tales, the giant squid is thought to reach some 60 feet in length. Despite the public’s fascination with this deep-sea animal, the giant squid’s life and habits are obscure. What little we know about the squid has mostly been based on dead and dying specimens hauled up by commercial fishing boats or animals washed ashore.

An intimidating predator, the giant squid has eight arms and two longer feeding tentacles that help the animal shelve food into its beaklike mouth. It is believed that the creature feeds largely on fish, shrimp, and other squid. Along with their relatives the colossal squid, the giant squid has the largest eyes in the animal world, measuring 10 inches in diameter. While certainly scary, the huge orbs are necessary to navigate the squid’s lightless habitat.

Usually, giant squid are found in deep-water fisheries off Spain and New Zealand. However, remains of some of the creatures have been found in the Gulf of Mexico as well. As recently as last year, scientists netted a deceased twenty foot giant squid off the Louisiana coast. It was the first time that one of the creatures had turned up in the vicinity since 1954, when another giant squid was found floating dead off the Mississippi Delta. The find demonstrated just how little scientists knew about what was swimming around in the inky depths of the Gulf of Mexico.

The delicate deep water ecology, about which we know so very little, is now being disrupted by the BP spill. Unfortunately, the giant squid is not the only animal inhabiting deep waters which could be impacted. Indeed, the demise of the giant squid will have a ripple effect further up the food chain. From examining the stomach of sperm whales inhabiting the Gulf of Mexico, we know that these endangered cetaceans feed on giant squid. In fact, it may be that the two huge animals have long squared off as titanic opponents: some believe that giant squid in turn could attack and eat small whales.

Sperm whale diving in the Gulf of Mexico. Photo by: NMFS. |

Experts hope the sperm whale may one day lead them to the giant squid, and have attached cameras to the cetaceans with the notion of glimpsing the elusive animal. Moreover, several years ago researchers launched a submarine expedition to the DeSoto canyon off the coast of Pensacola. Once there, they explored pinnacles of the canyon’s western wall. We need more such expeditions, particularly now as the sperm whale is facing a number of imminent threats associated with the oil industry.

Having its preferred meal of choice eliminated from its diet is bad enough, but consider that as it surfaces to breathe, the sperm whale can suck up oil if the animal finds itself in the midst of a slick. In addition, fumes on the surface are so powerful that they can knock out and drown full-grown whales. In an ominous sign, scientists recently spotted a dead sperm whale floating some 70 miles from the Deepwater Horizon rig. Experts are running tests to determine the animal’s cause of death.

Under the U.S. Endangered Species Act, all sperm whales are considered endangered, however the Gulf of Mexico population is considered to be particularly vulnerable owing to its small size. According to researchers, whales roaming the Gulf are genetically distinct from those found elsewhere and off the Texas and Louisiana coasts the cetaceans are smaller and make distinct sounds. The Gulf population is so endangered that if the BP spill kills just three sperm whales this could imperil the area’s native whale numbers. That is because sperm whales, particularly females, take a long time to reach sexual maturity. What’s more, females only give birth to three or four calves over the course of their lifetimes.

Like the giant squid, the sperm whale is one of the least understood creatures. One of the largest of all toothed whales, the creature can grow to lengths of 60 feet or more and live to more than sixty years of age. Seldom seen, it dives far offshore and as deep as 7,000 feet. Because it is so dark where the whale feeds, the animal relies on clicking and buzzing sounds to find its prey — a natural form of sonar called echolocation. Once hunted for its oil, the sperm whale was featured in Herman Melville’s classic novel Moby Dick.

Once thought to be a simple and unproductive ecosystem, the Gulf of Mexico has proven itself to be full of surprises. From the sperm whale to the giant squid, the Gulf holds many secrets in its inky depths. In the wake of the BP disaster, we should hit the pause button on further oil development and launch further scientific expeditions to learn more about the giant squid and its mysterious undersea world.

Nikolas Kozloff is the author of No Rain in the Amazon: How South America’s Climate Change Affects the Entire Planet (Palgrave, 2010). Visit his website, nikolaskozloff.com

Giant squid. Photo by: NASA.

Display at the New York City Museum of Natural History showing the imagined, but never before witnessed, struggle between a sperm whale and the giant squid. Photo by: Mike Goren.

Related articles

Goodbye to the Gulf: oil disaster hits region’s ‘primary production’

(07/08/2010) According to a new analysis by the World Resources Institute (WRI), the many ecosystem services provided by the Gulf of Mexico will be severely impacted by BP’s giant oil spill. ‘Ecosystem services’ are the name given by scientists and experts to free benefits provided by intact ecosystems, for example pollination or clean water. In the Gulf of Mexico, such environmental benefits maintain marine food production, storm buffers, tourism, and carbon sequestration, but one of the most important of marine ecosystem services is known as ‘primary production’.

Will we ever know the full wildlife toll of the BP oil spill?

(06/08/2010) Will we ever know the full wildlife toll of the BP oil spill? The short answer: no. The gruesome photos that are making the media rounds over the last week of oiled birds, fish, and crustaceans are according to experts only a small symbol of the ecological catastrophe that is likely occurring both in shallow and deep waters. Due to the photos, birds, especially the brown pelican, have become the symbol of the spill to date. But while dozens of birds have been brought to rescue stations covered in oil, the vast majority will die out at sea far from human eyes and snapping cameras, according to Sharon Taylor a vet with the US Fish and Wildlife Service.

BP and the Perilous Voyage of Bama the Manatee

(05/23/2010) To the degree that Americans are paying attention to the environmental plight of marine wildlife in the Gulf of Mexico, they may focus most upon dolphins and whales. However, the U.S. public is much less familiar with another marine mammal, the manatee, which could also be placed in jeopardy as a result of the BP oil spill. One of the most outlandish creatures on the planet, the shy and retiring manatee, which gets its name from an American Indian word meaning “Lady of the Water”, is one of my favorite animals.