Not surprisingly, a US report released last week which argued that saving forests abroad will help US agricultural producers by reducing international competition has raised hackles in tropical forest counties. The report, commissioned by Avoided Deforestation Partners, a US group pushing for including tropical forest conservation in US climate policy, and the National Farmers Union, a farmers’ group, has threatened to erode support for stopping deforestation in places like Brazil. However, two rebuttals have been issued, one from international environmental organizations and the other from Brazilian NGOs, that counter findings in the US report and urge unity in stopping deforestation, not for the economic betterment of US producers, but for everyone.

“The study has been used in recent days by several Brazilian parliamentarians and rural leaders to defend the idea that forest protection in Brazil is something that runs counter to the national interest,” explains a letter from 10 Brazilian NGOs. “With that, they want to justify the need for approving a bill that dramatically changes the Brazilian forest legislation. In this story, however, are American and Brazilian rural leaders are both mistaken.”

Clearing for pasture in the Amazon borders a legal forest reserve. Photo by: Rhett A. Butler. |

While the report, entitled “Farms Here, Forests There: Tropical Deforestation and U.S. Competitiveness in Agriculture and Timber” argues that US agricultural producers could save $49 billion between 2012 and 2030 simply by complying with climate change legislation, it pushes revenue from stopping deforestation abroad as the real cache. According to the report, US farmers could gain $141-$221 billion during the same time period from less competition abroad due to decreases in illegal forest clearing.

But according to the Brazilian NGOs the US report “ignores the Brazilian reality”.

“It is wrong to assume that an end to deforestation around here would stop the expansion of production of agricultural commodities at competitive prices. According to data from University of São Paulo/ESALQ, we have at least 61 million hectares of high potential agricultural land currently occupied by low productivity of livestock and can be quickly converted into areas of agricultural expansion,” the rebuttal states, adding that “we could double our production of food without having to bring down new forest and still recovering those areas where reforestation is done needed for their potential to provide ecosystem services.”

The Brazilian NGOs, including Conservation International-Brazil and the Institute of Man and Environment in the Amazon (IMAZON), further argue that halting deforestation in the Amazon is for the benefit not of US agricultural producers, but of the Brazilian public.

“The supply of forest products, regulation of water and climate, maintenance of biodiversity, environmental services are all provided exclusively by forests and essential to support national agriculture,” the rebuttal reads. In fact, Brazilian business leaders participating in the Sustainable Amazon Fórum (Fórum Amazônia Sustentável) recently voiced support for a national plan to reduce deforestation in order to preserve these ecological services, while leveraging best environmental practices to become competitive in the international marketplace. Their coalition was a key reason why Brazil called for strong action on reducing greenhouse gas emissions during last December’s climate talks in Copenhagen.

According to the letter, some Brazilian politicians are undermining greenhouse gas emission pledges by using the US report to support deforestation throughout the Amazon.

But it’s not just Brazilians that found the report misleading at best. Large international and US environmental groups have also released a rebuttal to the report, where they “reject the hypothesis that conservation of tropical forest can provide a competitive advantage for U.S. agriculture against competition from developing countries in agricultural commodities”.

According to the rebuttal, signed by Conservation International (CI), Environmental Defense Fund, The National Wildlife Federation, and the Nature Conservancy (TNC), “the report is based on the assumption, totally unfounded, that deforestation in tropical countries can be easily interrupted, and its conclusions are therefore also unrealistic.” However, the report follows the same timeline as the REDD program assumes: achieving a 50 percent drop by 2020 and a complete end to deforestation by 2030.

The rebuttal further argues that for deforestation to be slowed or stopped cannot mean that one nation (the US) will win out against others, but must “provide economic incentives for developing countries, including the producers, to maintain the native forest”. In fact, the strategy currently in place in the UN of paying tropical nations to keep their forests in tact known as REDD (Reduced Emissions from Deforestation and forest Degradation) proposes to do just this.

In addition the rebuttal agrees with Brazilian NGOs that production need not decrease in tropical forests nations if deforestation is stopped.

“Several scientific studies show that to reduce deforestation it is necessary to increase the competitiveness of agricultural production outside the forest frontier. Large tropical countries have large rural areas where underutilized whether to increase the productivity of agriculture without increasing deforestation.”

The environmental organizations also chided the US report for failing to point out the nation’s own responsibility (long the largest producer of greenhouse gas emissions in the world until superseded by China in 2006) in decreasing greenhouse gas emissions.

|

“This effort only makes sense when the United States—and developed countries as a whole—begin to substantially reduce emissions from all sectors of its economy. It is for this reason that these organizations support the establishment of a U.S. legislation on climate change with ambitious targets for reducing emissions,” the environmental groups write. They note that paying tropical nations to sustain forest cover must be a part of any plan to reduce global greenhouse gas emissions.

The US report was largely aimed at convincing US Republicans and wary rural Democrats to throw their support behind an energy and climate bill, but it has probably provoked a bigger reaction outside US borders. NGOs in Brazil, the US, and worldwide hope that by pointing out the report’s gaps abroad, they can re-focus the debate on the importance of saving forests, regardless of US farmers thousands of miles away.

While there has yet to be much reaction to the report in Asia, developers in Indonesia and Malaysia aren’t likely to be happy with its denigration of palm oil. The report calls for replacing palm oil use in the U.S. with domestic vegetable oil substitutes, which have a substantially lower yield, and therefore require more land, than the widely grown oil palm. Palm oil has drawn criticism from environmentalists however when rainforest and peatlands are cleared to establish plantations.

Ten signatories of Brazilian NGO letter

Friends of the Earth – Brazilian Amazon

Association for the Preservation of the Environment and Life-APREMAVI

SOS Mata Atlantica

Carajás Forum

Greenpeace

Conservation International – CI-Brazil

Amazon Working Group – GTA

Institute of Man and Environment in the Amazon – IMAZON

Instituto Centro de Vida – ICV

Socio-Environmental Institute

Related articles

Ending deforestation could boost Brazilian agriculture

(06/26/2010) Ending Amazon deforestation could boost the fortunes of the Brazilian agricultural sector by $145-306 billion, estimates a new analysis issued by Avoided Deforestation Partners, a group pushing for U.S. climate legislation that includes a strong role for forest conservation.

Saving tropical forests helps protects U.S. agriculture, argues campaign

(06/18/2010) Reducing deforestation abroad helps protect the U.S. agricultural sector by ensuring higher prices for commodities and reducing the cost of compliance with expected climate regulations, argues a new report issued by Avoided Deforestation Partners, a group pushing for the inclusion of tropical forests in domestic climate policy, and the National Farmers Union, a farming lobby group.

![]()

(05/04/2010) Most people who are trying to change the world stick to one area, for example they might either work to preserve biodiversity in rainforests or do social justice with poor farmers. But Dr. Ivette Perfecto was never satisfied with having to choose between helping people or preserving nature. Professor of Ecology and Natural Resources at the University of Michigan and co-author of the recent book Nature’s Matrix: The Link between Agriculture, Conservation and Food Sovereignty, Perfecto has, as she says, “combined her passions” to understand how agriculture can benefit both farmers and biodiversity—if done right.

(05/03/2010) Over the past 30 years billions of dollars has been committed to global conservation efforts, yet forests continue to fall, largely a consequence of economic drivers, including surging global demand for food and fuel. With consumption expected to far outstrip population growth due to rising affluence in developing countries, there would seem to be little hope of slowing tropical forest loss. But some observers see new reason for optimism—chiefly a new push to make forests more valuable as living entities than chopped down for the production of timber, animal feed, biofuels, and meat. While are innumerable reasons for protecting forests—including aesthetic, cultural, spiritual, and moral—most land use decisions boil down to economics. Therefore creating economic incentives to maintaining forests is key to saving them. Leading the effort to develop markets ecosystem services is Forest Trends, a Washington D.C.-based NGO that also organizes the Katoomba group, a forum that brings together a wide variety of forest stakeholders, including the private sector, local communities, indigenous people, policymakers, international development institutions, funders, conservationists, and activists.

Large-scale soy farming in Brazil pushes ranchers into the Amazon rainforest

(04/28/2010) Industrial soy expansion in the Brazilian Amazon has contributed to deforestation by pushing cattle ranchers further north into rainforest zones, reports a new study published the journal Environmental Research Letters.

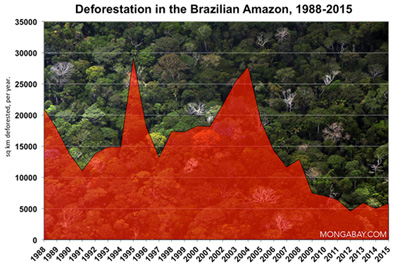

United States has higher percentage of forest loss than Brazil

(04/26/2010) Forests continue to decline worldwide, according to a new study in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Science (PNAS). Employing satellite imagery researchers found that over a million square kilometers of forest were lost around the world between 2000 and 2005. This represents a 3.1 percent loss of total forest as estimated from 2000. Yet the study reveals some surprises: including the fact that from 2000 to 2005 both the United States and Canada had higher percentages of forest loss than even Brazil.

World failing on every environmental issue: an op-ed for Earth Day

(04/22/2010) The biodiversity crisis, the climate crisis, the deforestation crisis: we are living in an age when environmental issues have moved from regional problems to global ones. A generation or two before ours and one might speak of saving the beauty of Northern California; conserving a single species—say the white rhino—from extinction; or preserving an ecological region like the Amazon. That was a different age. Today we speak of preserving world biodiversity, of saving the ‘lungs of the planet’, of mitigating global climate change. No longer are humans over-reaching in just one region, but we are overreaching the whole planet, stretching ecological systems to a breaking point. While we are aware of the issues that threaten the well-being of life on this planet, including our own, how are we progressing on solutions?

Commodity trade and urbanization, rather than rural poverty, drive deforestation

(02/07/2010) Deforestation is increasingly correlated to urban population growth and trade rather than rural poverty, suggesting that measures proposed to reduce deforestation will be ineffective if they fail to address demand for commodities produced on forest lands, argues a new paper published in Nature GeoScience.

-

NOTA PÚBLICA: CÓDIGO FLORESTAL, DESMATAMENTO ZERO E COMPETITIVIDADE AGRÍCOLA

Recentemente lançado nos Estados Unidos, o estudo “Fazendas aqui, florestas lá”, patrocinado pela organização National Farmers Union (União Nacional de Fazendeiros), principal sindicato rural norte-americano, e apoiado pela Avoided Deforestation Partners (Parceiros pelo Desmatamento Evitado) – uma aliança informal de pessoas e organizações que defendem o fim do desmatamento no mundo, foi feito para promover a aprovação da lei de mudanças climáticas, em tramitação no Senado americano. Um dos dispositivos desse projeto de lei prevê a possibilidade de que grandes poluidores norte-americanos possam compensar suas emissões de gases do efeito estufa, financiando a proteção de florestas em países tropicais. É o caso da Indonésia e do Brasil, onde o desmatamento torna esses dois países o terceiro e o quarto maiores poluidores do clima no planeta, respectivamente.

Elaborado com a intenção de convencer parte da bancada republicana – contrária à lei – a mudar de posição, sobretudo a pertencente a estados com grande produção agropecuária, o estudo defende que o investimento em mecanismos de desmatamento evitado em países tropicais elevaria os ganhos da agricultura norte-americana, não só diminuindo os custos com a mudança de tecnologia para reduzir a emissão de gases do efeito estufa, mas, sobretudo, afastando a competição de produtores rurais desses países, que hoje competem diretamente com os americanos pelos mercados de commodities agrícolas. Segundo o estudo, os ganhos poderiam alcançar US$ 270 bilhões entre 2012 e 2030 só com a diminuição da competição dos países tropicais.

Em função dessa conclusão infundada, esse estudo vem sendo usado, nos últimos dias, por diversos parlamentares e lideranças ruralistas brasileiros para defender a tese de que a proteção de florestas no Brasil é algo que contrariaria o interesse nacional. Com isso, querem justificar a necessidade de aprovação de um projeto de lei que altera dramaticamente a legislação florestal brasileira. Nessa história, no entanto, estão enganados os ruralistas norte-americanos e os brasileiros.

Em primeiro lugar o estudo, que desconhece a realidade brasileira, é equivocado ao assumir que o fim do desmatamento por aqui significaria paralisar a expansão da produção de commodities agrícolas a preços competitivos. Segundo dados da Universidade de São Paulo/Esalq, temos pelo menos 61 milhões de hectares de terras de elevado potencial agrícola hoje ocupadas por pecuária de baixa produtividade e que podem ser rapidamente convertidas em áreas de expansão agrícola. Com o fim da expansão horizontal da fronteira agrícola, há forte tendência de valorização da terra e de substituição dos sistemas de produção agropecuária de baixa produtividade (que garimpam os nutrientes e degradam o meio ambiente) por sistemas de produção mais intensivos e com maior produtividade. Estudos da Embrapa mostram que há um cenário ganha-ganha quando se incorpora tecnologias (recuperação de áreas de pastagens degradadas, agricultura com plantio direto, sistemas integrados de lavoura-pecuária e lavoura-pecuária-floresta) nas áreas atualmente ocupadas com agricultura e pecuária, aumentando a produção, reduzindo custos e emissões de gases do efeito estufa. No caso do Brasil, onde 4/5 das terras agricultáveis são ocupadas por pastagens, tais ganhos são especialmente expressivos – de forma que poderíamos dobrar nossa produção de alimentos sem ter que derrubar novas áreas de floresta e ainda recuperando aquelas áreas onde o reflorestamento se faz necessário por seu potencial de prover serviços ecossistêmicos.

Portanto, o aumento da produção agrícola não passa necessariamente pelo aumento ou continuidade do desmatamento, como quer fazer crer o estudo norte-americano. Os produtores competitivos não são os que usam métodos do século XVIII, grilando terras públicas, desmatando e usando mão de obra escrava e sonegando impostos. Pelo contrário, são os que investem em tecnologia e mão de obra qualificada para o bom aproveitamento de terras com infraestrutura adequada. Por essa razão até mesmo a Confederação Nacional da Agricultura – CNA, afirma que não é mais necessário desmatar para aumentar e fortalecera produção agropecuária brasileira.

Não devemos esquecer que a preservação e a recuperação de florestas no Brasil interessam, antes de tudo, a nós mesmos. O fornecimento de produtos florestais, a regulação das águas e do clima, a manutenção da biodiversidade, são todos serviços ambientais prestados exclusivamente pelas florestas e indispensáveis à sustentação da agropecuária nacional.

Frente a isso, repudiamos não só as conclusões do estudo norte-americano, como a tentativa de usá-lo para legitimar propostas que, essas sim, atentam contra o interesse nacional, ao permitir o desmate de mais de 80 milhões de hectares e a anistia definitiva para aqueles já ocorridos, o que coloca em cheque a possibilidade de cumprirmos com as metas assumidas de redução de emissões de gases de efeito estufa e recuperar a oferta de serviços ambientais em regiões hoje totalmente desreguladas, algumas inclusive em desertificação. Aumentar a produção agropecuária com base no desmatamento de novas áreas é uma lógica com data marcada para acabar, tão logo os recursos naturais se esgotem e o clima se modifique. Não podemos, nesse momento em que o Código Florestal pode vir a ser desfigurado pela bancada ruralista do Congresso Nacional, nos desviar da discussão que realmente interessa ao país, que é saber se precisamos ou não das florestas para o nosso próprio bem-estar e desenvolvimento.

A defesa das florestas é matéria de alto e urgente interesse nacional.

Assinam:

Amigos da Terra – Amazônia brasileira

Associação de Preservação do Meio Ambiente e da Vida- APREMAVI

Conservação Internacional – CI-Brasil

Fundação SOS Mata Atlântica

Fórum Carajás

Greenpeace

Grupo de Trabalho Amazônico – GTA

Instituto do Homem e do Meio Ambiente da Amazônia – IMAZON

Instituto Centro de Vida – ICV

Instituto Socioambiental

Esclarecimento sobre o Relatório “Fazendas Aqui, Florestas Lá – Desmatamento Tropical e Competitividade Norte-americana na Agricultura e na Madeira”, elaborado pela organização Parceiros para o Desmatamento Evitado (Avoided Deforestation Partners’)

As organizações signatárias desta carta reconhecem que colaboraram recentemente com a organização “Parceiros para o Desmatamento Evitado” (Avoided Deforestation Partners) em prol da criação de uma legislação norte-americana de mudanças climáticas, inclusive para que esta tenha incentivos para reduzir o desmatamento tropical. Entretanto, rejeitam a hipótese de que a conservação da floresta tropical possa constituir uma vantagem competitiva para a agricultura norte-americana frente à concorrência dos países em desenvolvimento no mercado de commodities agrícolas. As organizações não se associam e não endossam as conclusões do relatório, que são de inteira responsabilidade da organização “Parceiros para o Desmatamento Evitado” (Avoided Deforestation Partners).

As organizações signatárias entendem que, para reduzir significativamente ou mesmo interromper o desmatamento das florestas tropicais, será necessário prover incentivos econômicos aos países em desenvolvimento, inclusive aos produtores, para manter a cobertura florestal nativa. Ao mesmo tempo, deve-se intensificar a produção agrícola em terras já desmatadas e/ou degradadas, bem como a consolidação do manejo florestal sustentável.

No entanto, salientamos que essa estratégia só terá êxito se beneficiar tanto os países tropicais quanto os não tropicais. O relatório “Fazendas Aqui, Florestas Lá – Desmatamento Tropical e Competitividade Americana na Agricultura e na Madeira”, elaborado pela organização Parceiros para o Desmatamento Evitado (Avoided Deforestation Partners’), identificou os benefícios potenciais de tal mecanismo para os produtores norte-americanos, mas não destacou os benefícios para os países tropicais – que podem ser substanciais. Nota-se que o relatório é baseado na suposição, totalmente infundadas, de que o desmatamento nos países tropicais poderá ser facilmente interrompido, e suas conclusões são, por conseguinte, igualmente irrealistas.

Diversos estudos científicos comprovam que para reduzir o desmatamento é necessário aumentar a competitividade da produção agrícola fora da fronteira da floresta. Grandes países tropicais contam com grandes áreas rurais subutilizadas onde se deve aumentar a produtividade da agropecuária sem aumentar o desmatamento.

As organizações signatárias reconhecem que a redução das emissões de gases de efeito estufa provenientes do desmatamento das florestas tropicais é fundamental para estabilizar o clima global. Entretanto, tal esforço só fará sentido quando os Estados Unidos – e os países desenvolvidos como um todo -, começarem a reduzir substancialmente as emissões provenientes de todos os setores da sua economia.

É por esta razão que estas organizações apoiam o estabelecimento de uma legislação norte-americana sobre mudança climática com metas ambiciosas de redução de emissões. Também entendem que estabelecer um mecanismo de incentivos para a redução das emissões resultantes do desmatamento e da degradação florestal poderá colaborar para que o esforço global de redução de emissões de gases de efeito estufa seja rápido e efetivo, ao mesmo tempo em que beneficia os países tropicais, comunidades locais, os povos da floresta e os agricultores.

Conservação Internacional

Environmental Defense Fund

National Wildlife Federation

The Nature Conservancy