The body charged with establishing a framework for a global climate treaty will account for emissions from peatlands degradation, a source of roughly 6 percent of greenhouse gas emissions.

The decision by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) lays the groundwork for new measures to protect and restore wetlands, says Wetlands International.

“Once emissions and removals from wetlands can be accounted for under the Kyoto Protocol the entire finance stream for wetland management will change”, said Susanna Tol of Wetlands International, a group that advocates for protection of wetlands. “Rewetting these important ecosystems and implementing sustainable use like paludiculture (wet agriculture) will become financially attractive.”

Draining and clearing of peat forest in Central Kalimantan. Photo by Rhett A. Butler. |

Until now, emissions accounting under IPCC methodological guidance largely ignored emissions reductions from wetlands restoration. Research has shown that “rewetting” peatlands is one of the most cost-effective approaches to reducing greenhouse gas emissions.

Peat ecosystems

Peatlands, formed by organic deposits comprised of partially decayed plant matter that accumulates over hundreds of years, cover more than 400 million hectares of land worldwide. Most of these exist in permafrost in the far north, though some are found in the lowlands of tropical Asia, especially in the swampy forests of Indonesia and Malaysia. Peatlands are giant reservoirs of carbon, with those in Southeast Asia locking up 42 billion tons of carbon, according to Wetlands International. However, when peatlands are drained, cut, or burned, this stored carbon is released into the atmosphere, contributing to climate climate.

Each year hundreds of thousands of hectares of peatlands are drained and cleared for oil palm and timber plantations on Indonesia and Malaysia. Generally, developers dig a canal to drain the land, extract valuable timber, then clear the vegetation using fire. In dry years, these fires can burn for months, contributing to the “haze” that regularly plagues Southeast Asia. Fires in peatlands are especially persistent, since they can smolder underground for years even after surface fires are extinguished by monsoon rains.

Burning is the source of about 70 percent of emissions from peatlands, but merely draining peatlands also contributes to global warming—upon exposure to air, peat rapidly oxidizes, decomposes, and releases carbon dioxide. Degradation and destruction of forests growing on top of peatlands is a further source of emissions.

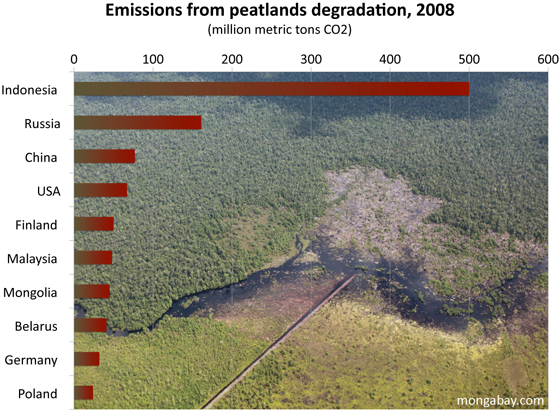

But peatlands degradation isn’t limited to Southeast Asia. Peat is drained for agriculture and forestry and mined for horticulture and fuel in Europe and China. Emissions from E.U. countries amount to 174 million tons per year and 160 million tons per year in Russia, according to a study published last year. In Sub-Sahara Africa (excluding South Africa) peat emissions equal 25% of all fossil fuel emissions. Overall global peatland emissions have increased by ore than 20 percent since 1990.

Beyond contributing to climate change, destruction of peatlands in Indonesia puts local populations at greater risk of flooding. Peatlands are a natural means of flood control, acting like a sponge to absorb large amounts of rainfall and runoff, while reducing the threat of erosion.