| Français: Madagascar reprend ses exportations de bois de rose exploités illégalement et cela malgré le moratoire |

Albert Camille Vital, Madagascar’s Prime Minister under the regime that seized power during a coup on the Indian Ocean island nation last year, approved this week’s shipment of nearly $16 million worth of timber illegally logged from the country’s rainforest parks, according to documents provided to mongabay.com.

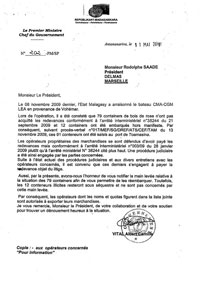

Vital sent a letter to Rodolphe Saade, president of Delmas, a Marseilles-based shipping company that was criticized last year for its role in facilitating the destruction of Madagascar’s national parks, authorizing the shipment of of 79 containers of rosewood from the port of Toamasina (Tamatave). After receiving the authorization May 11, Delmas asked the French embassy on May 18 for advice on the shipment. The French ambassador told Delmas not to proceed with the shipment due to fears of international outcry.

On May 20, Madagascar’s Minister of Finance asked a second shipping company, SEAL/Pacific International Lines, to load the containers. SEAL/PIL agreed and its ship, the Terra Bonna sailed from Toamasina on June 6.

Rosewood logging in Masoala National Park, a UNESCO World Heritage Site. Photo by Rhett A. Butler |

At present it is unclear where the rosewood is headed, but most of the buyers on the manifest are based in China. The companies include China Tushu Shanghai Pudong Import & Export Corporation, Shanghai Tan Tan Trade Co Ltd, Dalian Rising International Trading Co, High Hope International Group Jiang Knit Wear & Home Textiles Import & Export Corporation Ltd, Shanghai Tan Tan Trade Co Ltd, Jiangsu Bosheng International Freight & Forwarding Co Ltd, China Meheco Traditional Medecines and Health Products Import and Export Corp., and Shanghai Tan Tan Trade Co Ltd.

The sellers are Madagascar-based traders, including Arland Ramialison with 13 containers weighing 209 metric tons; Jean-Pierre Laisoa with 10 containers weighing 610 tons; Jean-Michel Malohely with 10 containers weighing 153 tons; Ranjanoro Ets with 10 containers weighing 170 tons; and Société Thunam, a company that supplies Theodor Nagel, a German timber company based in Hamburg, among others, with 29 containers weighing 516 tons.

Rainforest Massacre in Madagascar

Document authorizing the shipment of rosewood from Tamatave. Page 1 | Page 2 | Page 3 | Page 4 | Page 5 Ex Lea containers shipped by SEAL/PIL on Terra Bona in June 2010 |

Madagascar’s rainforest parks were pillaged in the aftermath of the March 2009 coup which saw the democratically elected, but increasingly autocratic Marc Ravalomanana, chased out of the country at gun point by army officers supporting Andry Rajoelina, then mayor of Madagascar’s capital Antananarivo. Despite being too young to hold office under Madagascar’s constitution and having little political experience, Rajoelina has clung to power since the coup.

In the months following the power grab, Madagascar’s reserves were ravaged by illegal loggers. Armed bands, financed by foreign timber traders and at times in collusion with local officials, went into Marojejy and Masoala national parks, harvesting valuable hardwoods including rosewood and ebonies. Without backing from the central government or support from international agencies that had been the source of nearly 90 percent of conservation funding, little could be done to stop the carnage

Marojejy, a forested mountain that is among Madagascar’s most biodiverse parks with a dozen species of lemurs including the critically endangered Silky Sifaka, was the first to fall. Loggers invaded the reserve, cutting trails, hunting wildlife, and extracting timber. Those who attempted to stand in their way were threatened—local radio reported that a park ranger from ANGAP, Madagascar’s protected areas agency, had both of his feet broken by representatives of timber barons in the northern town of Mananara. The chaos forced authorities to close Marojejy to tourists—its lifeblood—for the first time, effectively blocking outsiders from bearing witness so the plunder. Loggers soon moved into Masoala National Park, a UNESCO World Heritage site that is considered one of the jewels of Madagascar’s protected areas. Logging was so intense in Masoala that the supply of cargo boats in the neighboring town of Maroantsetra was fully employed to haul rosewood out of the forest—none were available for conventional shipping. Other forest areas were also targeted. All told, logging affected 27,000-40,000 acres of protected rainforest, according to estimates from Lucienne Wilmé, Porter P. Lowry, Peter H. Raven of the Missouri Botanical Garden, and Derek Schuurman of Rainbow Tours. More than $200 million worth of timber was cut. Much of it went to China to make wood products that will eventually be sold in Europe and the United States.

Rosewood logs.

|

Until the coup, ecotourism had been an economic bright spot for Madagascar. Lured by its spectacular landscapes, unmatched biodiversity, and cultural richness, tourist arrivals had been growing, reaching $390 million in 2008. But the trend shifted abruptly with the political turmoil and violence, with rich-world governments advising their citizens to avoid Madagascar. Tourist arrivals dropped sharply during the crisis—50 to 60 percent island-wide for the year by some estimates. International carriers cut flight service but workers employed directly in the tourism industry were particularly affected.

The decline in tourism had been felt widely in Madagascar, but some suffered more than others. During a visit by mongabay.com last October, some operators in the north said business was down by as much as 80 percent relative to last year. In Ranomafana, arguably Madagascar’s best-managed park, tourist arrivals were down by more than 40 percent, according to Patricia Wright, executive director of the Institute for the Conservation of Tropical Environments (ICTE) at Stony Brook University and a leading force in conservation in Madagascar over the past 20 years. Wright has tracked tourism in Ranomafana over the past decade and sais that during Madagascar’s last political crisis in 2002, tourist arrivals in Ranomafana fell from 16,000 to less than 3,000, a drop of more than 80 percent. Last year 24,000 tourists visited the park, generating $1.72 million in revenue. The standstill also hit downstream businesses indirectly linked with tourism. Farmers sold less rice and zebu, shopkeepers sold fewer bottles of Eau Vive, the ubiquitous drinking water most often consumed by tourists, and bundles of fresh vanilla beans, a popular souvenir.

For conservation, the fall in tourist revenue was exacerbated by the loss of donor support. USAID, a major source of finance for conservation projects, and other organizations froze funding, while the Peace Corps pulled its volunteers out of the country. Zurich Zoo, which backs a conservation project in Masoala, gathered thousands of signatures in a petition drive, calling for restoration of law enforcement and resumption of aid. There were worries that the suspension of projects has eroded confidence among local communities that conservationists are committed to Madagascar for the long haul.

While the situation improved in the second half of 2009, with gendarmerie moving into some critical areas and a series of arrests of illegal loggers (who were subsequently released), the situation deteriorated toward the end of the year until a campaign launched by Ecological Internet, an Internet-based activist group, forced Delmas, which had planned a shipment worth $20-80 million, to leave port without any timber. A representative from Delmas said afterward that transporting the timber wasn’t worth the damage to its reputation.

But the reprieve didn’t last long. On December 31, Rajoelina’s transitional authority authorized the export of rosewood, signaling to loggers that they could then cash in on their efforts. Immediately following the decree, reports on the ground indicated an upswing in logging activity in Masoala and Makira National Parks, but timber was still not leaving the country due to continued pressure from environmentalists. In March, after a rosewood shipment finally left Madagascar, intense international outcry led Rajoelina to issue a two-year moratorium on timber shipments. But with Sunday’s shipment by SEAL/PIL, it is now clear the government does not intend to maintain the ban. Expect logging of Madagascar’s parks to resume.

Earlier articles

How to end Madagascar’s logging crisis

(02/10/2010) In the aftermath of a military coup last March, Madagascar’s rainforests have been pillaged for precious hardwoods, including rosewood and ebonies. Tens of thousands of hectares have been affected, including some of the island’s most biologically-diverse national parks: Marojejy, Masoala, and Makira. Illegal logging has also spurred the rise of a commercial bushmeat trade. Hunters are now slaughtering rare and gentle lemurs for restaurants.

Satellites being used to track illegal logging, rosewood trafficking in Madagascar

(01/28/2010) Analysts in Europe and the United States are using high resolution satellite imagery to identify and track shipments of timber illegally logged from rainforest parks in Madagascar. The images could be used to help prosecute traders involved in trafficking and put pressure on companies using rosewood from Madagascar.

Coup leaders sell out Madagascar’s forests, people

(01/27/2010) Madagascar is renowned for its biological richness. Located off the eastern coast of southern Africa and slightly larger than California, the island has an eclectic collection of plants and animals, more than 80 percent of which are found nowhere else in the world. But Madagascar’s biological bounty has been under siege for nearly a year in the aftermath of a political crisis which saw its president chased into exile at gunpoint; a collapse in its civil service, including its park management system; and evaporation of donor funds which provide half the government’s annual budget. In the absence of governance, organized gangs ransacked the island’s biological treasures, including precious hardwoods and endangered lemurs from protected rainforests, and frightened away tourists, who provide a critical economic incentive for conservation. Now, as the coup leaders take an increasingly active role in the plunder as a means to finance an upcoming election they hope will legitimize their power grab, the question becomes whether Madagascar’s once highly regarded conservation system can be restored and maintained.