- Indigenous groups in the Colombian Amazon have long suffered deprivations at the hands of outsiders.

- First came the diseases brought by the European Conquest, then came abuses under colonial rule.

- In modern times, some Amazonian communities were virtually enslaved by the debt-bondage system run by rubber traders: Indians could work their entire lives without ever escaping the cycle of debt.

- But new hope would emerge in the 1980s, thanks partly to the efforts of Martin von Hildebrand, an ethnologist who would help indigenous Colombians eventually win control over 260,000 square kilometers of Amazon rainforest.

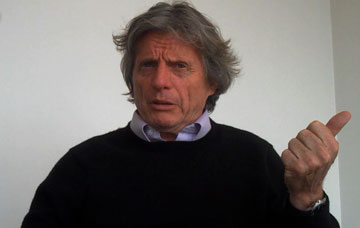

An interview with Martin von Hildebrand, founder at head of Gaia Amazonas.

Indigenous groups in the Colombian Amazon have long suffered deprivations at the hands of outsiders. First came the diseases brought by the European Conquest, then came abuses under colonial rule. In modern times, some Amazonian communities were virtually enslaved by the debt-bondage system run by rubber traders: Indians could work their entire lives without ever escaping the cycle of debt. Later, periodic invasions by gold miners, oil companies, colonists, and illegal coca-growers took a heavy toll on remaining indigenous populations. Without title to their land, organization, or representation, indigenous Colombians in the Amazon seemed destined to be exploited and abused.

But new hope would emerge in the 1980s, thanks partly to the efforts of Martin von Hildebrand, an ethnologist who would help indigenous Colombians eventually win control over 260,000 square kilometers (100,000 square miles) of Amazon rainforest—an area larger than the United Kingdom.

Martin von Hildebrand on the sidelines of the Skoll World Forum in April 2010. Photo by Rhett A. Butler. |

Von Hildebrand first visited the Colombian Amazon in 1970, spending four months living amongst remote indigenous communities. He found them exploited by rubber traders and deprived of basic human rights. Indigenous communities were in decline as youths abandoned their homeland for towns and traditional knowledge was lost with each passing elder.

Living with tribes during the 1970s, von Hildebrand learned of the traditional land management practices of indigenous societies as well as their philosophies of co-existing with the rainforest. He helped free communities from the tyranny of rubber and started developing an education system for the indigenous. Inspired to help them win title to their territory and therefore greater autonomy, von Hildebrand joined the Colombian government in 1986, as Head of Indigenous Affairs and adviser to President Virgilio Barco Vargas. In government von Hildebrand helped push through legislation that would lead to the establishment of 20 million hectares of collective indigenous territory—a move that would become a fundamental part of the country’s 1991 constitution.

Winning recognition of land rights however was only a first step towards autonomy so in 1990 von Hildebrand founded Fundacion Gaia Amazonas to establish a governance structure that would allow indigenous to have greater control over their health and education systems, and the fate of their rainforest environment. Today von Hildebrand serves as head of both Gaia Amazonas and the COAMA Program, a coalition of NGOs that aims to strengthen ties between indigenous groups across Colombia, Brazil and Venezuela to help them develop sustainable livelihoods and approaches to self-governance. The alliance includes 250 indigenous communities across 22 tribes. Some 70 million hectares (270,000 square miles) have been recognized as Indigenous collective property, but tribes are looking to double that amount. Gaia Amazonas is working with several NGOs, the Ministry of Environment and National Parks on a strategy to conserve 80 percent of the Colombian Amazon.

Over the course of his life’s work, von Hildebrand has been honored with many accolades including the Right Livelihood Award (Sweden—1999), the National Environmental Prize (Colombia—1999), Order of the Golden Ark (The Netherlands—2004), National Prize of Ecology (Colombia—2004), and the Skoll Foundation’s Social Entrepreneur Award in 2009.

Mongabay had an opportunity to talk with von Hildebrand at the 2010 Skoll World Forum at Oxford University.

AN INTERVIEW WITH MARTIN VON HILDEBRAND

mongabay.com:

What is your background and how did you end up working with indigenous communities in Colombia?

MARTIN VON HILDEBRAND: I went into the forest for the first time in 1970 as a potential anthropologist. I wanted to learn from the indigenous people. It was very remote—and still is. There are no roads—in fact I rode in and it took about five months. And I went and I met these people and I found them mainly exploited in rubber camps and their kids going to missionary schools where they were taught not to be Indians, fundamentally.

I got involved and tried to see how they could get rid of this. I spent the Seventies helping them look into the possibility of their getting rights to their land to stop the white people from coming in. Getting recognition of their land would open spaces for them to be themselves, to think for themselves, to be able to develop according to the way they want to develop, to get them out of the destructive bonds with the rubber traders, and to start schools.

We did manage to get rid of rubber people. They didn’t get the land but we did the studies and we started with the schools.

In the Eighties I had a chance to get into government, for the Ministry of Education and then the Presidency. And then we managed to push through all the laws to recognize indigenous land rights and get the schools in place.

The result: by the end of the Eighties we had over 20 million hectares (50 million acres) of land—about the size of the United Kingdom. Now there is 25 million hectares. We had indigenous people’s rights set in Congress. We participated in defining and writing up the ILO Convention No. 169 [International Labor Organization Convention No. 169, the framework for securing indigenous rights in Colombia] and getting it ratified in the country.

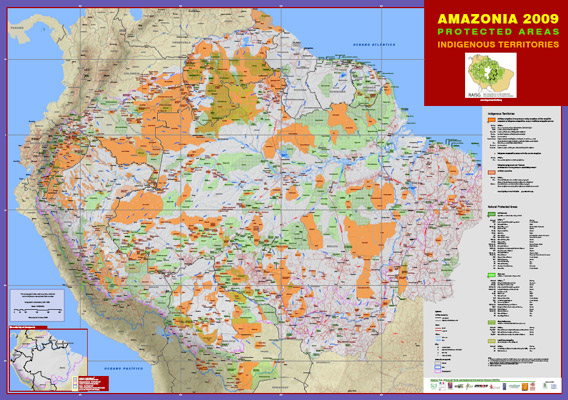

2009 Amazon Protected Areas and Indigenous Territories. Image courtesy of the Red Amazónica de Información Socioambiental Georreferenciada (RAISG). High resolution. |

So by the end of the Eighties we had the things basically in place. We had won what we were trying to get for the Amazon: over fifty percent of the Amazon in indigenous people’s hands. The indigenous people had inalienable ownership.

So in the end I went down into the field with the NGOs working in the area and we started supporting indigenous people for the full management of their land. We started by taking on very small communal projects until there were a couple of hundred projects going.

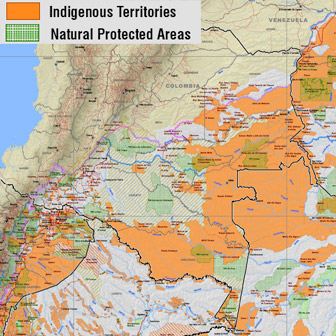

Closeup for Colombia on the Red Amazónica de Información Socioambiental Georreferenciada (RAISG) map. Click image to enlarge. |

We accompanied them in the process of setting up a system of local governance. They started doing research on their own environment, developing their own educational programs based on own traditional knowledge but also articulating with the outside world.

And by the beginning of 2000 they went to the government and said “Okay, we have developed our programs and now we want to decentralize and be officially recognized as the people who run this part of the world—our territory.”

The government didn’t agree to this but eventually we took them to court, and we went through the normal processes that happen when someone has to go to court. Of course for fundamental rights—like education, health, work, or livelihood—it takes several months to make a decision.

So we managed to get that going. During these ten years, there was a lot of work with the government on decentralization and the government learning how to understand indigenous cultures, cultural diversity, and other ways to set up education and health. Meanwhile the indigenous people learned how to handle governmental mechanisms: public funds and the systems.

Now we are confronted with climate change, which is a global issue and therefore requires moving out and forward to form new alliances and look for new funds. We want indigenous governance to be sustainable in the long run.

We also want indigenous people to become full citizens—as a community, but full citizens—receiving government services as a national community. This will give them independent funds to do what they want to do, which is recuperate the full management of their territory and have more autonomy so they can sit at the table with the government and industry and determine the fate of their land. They will have land, income, and political power.

mongabay.com:

You mention the concept of “harvesting funds”—a comparison to the harvest of game, fruit, or food crops. Do you envision this harvest being augmented by forest carbon funds that recognize indigenous ownership and stewardship of land.

MARTIN VON HILDEBRAND: Exactly. Right now the Colombian government—like almost all governments of the world—have a fund for education and health. For indigenous territories, the indigenous receive that money and determine how it is used for health and education. The indigenous are also doing a lot of research directed by their shamans—their own people.

Clearing in the Colombian Amazon. Photo taken by Rhett Butler in March 2010. |

And it is very interesting because of what is coming out of this research on their policy, their rituals, the annual cycles; how nature changes, how they adapt to the changes in nature, and their sacred sites. Sacred sites are different from protected areas—they are much larger and are based on energy flow and restriction. For example, instead of just protecting a part of your body, like your leg, it is like the acupuncturist picking the key points across your entire body and taking care of these points to keep the energy flowing through restriction, depending on the time of year and the season.

So it is a new paradigm on how to approach the conservation of very large areas in ecosystems—more than just biodiversity. So we are looking into that a lot—with a lot of potential. Not only because of the forest, but because of the knowledge—built over thousands of years—of the forest. This research will be very useful for us in the future since it will be used to set very precise programs where the money will be going.

But the important part of REDD I think—if we get REDD or REDD+ for the forest—is that the money would go towards a long-term plan that would be a commitment between the government and indigenous people to conserve the rainforest and strengthen indigenous traditional knowledge.

REDD projects should have activities which are clearly defined and monitored by an external committee; the same way as the money be monitored if it were an external fund.

The monitoring is important because there is a danger of corruption if it is in the hands of the government. But the same with the Indians because the money can lead to individualism, power conflict, and cultural deterioration.

So it should be the plan, not the powers that are given the money. Now, if there is money left over, it should be invested in other environmental plans and other indigenous projects. For example indigenous people may come to the point where they decide to put drinking water in a town. They administer their territories but have also begun co-administrating other territories, including towns.

mongabay.com:

Mapping has been a key component in establishing lands rights for indigenous communities in the Colombian Amazon. Has technology been important in the effort?

MARTIN VON HILDEBRAND: It involves very basic technology. Mapping the land is the non-technological part of the job. What happens in mapping the land is they make the drawings. What is important in the mapping is not the map itself; it is the relation that they have with the environment. So how you relate to the different hunting areas, to the different fishing areas, to the food areas, to the Sacred Sites. And how does that vary in time—in the different seasons? They have the seasons there defined to come up with when different foods are harvested or cultivated. So it is this relationship with the environment that comes up in the mapping. And the relationship with the environment is different for the women and for the men; for the young and for the old; for the hunter, for the fisher. And once you have the map, you keep it as a basis for knowledge.

Heliconia in the Colombian Amazon. Photo taken by Rhett Butler in March 2010. |

The time aspect is important because things change depending on the time of year. But this methodology of looking at the cycles of the year also becomes the agenda for the school—the curriculum. The curriculum goes by each season and once you start talking about how you relate to the season with children it ties in with a variety of subjects like the behavior of animals (ecology), how many are hunted (arithmetic), as well as strengthening the bond between generations since children talk with their parents to get information.

As they systematize the information it becomes a powerful tool in decentralization. For example when the government comes in with a plan for health or the environment, the indigenous can ask, “Where is your data to support this plan?” Usually the government doesn’t have the data but the community does. It can respond “The environment here is like this, and this comes at this time of the year, and the money has to go here, and here, and here.”

And the government does it! The government does it because the indigenous people have the data. They can show how nature behaves, how health behaves, how their relation with the environment behaves. So it gives them a tremendous tool and power because they can feel that they are being recognized, they are respected, and because the government ends up doing what they say.

So in fact they are administrating these territories. This doesn’t involve that much technology because they take their knowledge and the technology, put it in order and write it up systematically. They do it every day—they are very disciplined people. They have grown up with discipline since they were children. You know, just like making baskets where you have to focus on each fiber in the basket. Because what is extraordinary about baskets—if you make one tiny mistake, when you have finished the basket and one end of the fiber doesn’t tie in with the other, you have to undo the whole basket and start again! And so you learn to pay attention, no? You learn to concentrate.

And so it all goes together. It is a way of life where the indigenous people are patient and perseverant. When they are hunting they have to be so careful—the sound, the noise, the way they move.

So this is like what we could call “science”. They like to get the data, to put it in order, to think. And they enjoy it when they fulfill demands. But they have to be precise.

mongabay.com:

You have worked in this region for a long time. Have you seen cultural shifts in terms of younger generations becoming more interested in moving to cities and having some of the perceived luxuries of city life?

MARTIN VON HILDEBRAND: When I first went in they were slaves to rubber. Now they own the land, they have their own government, and they are deciding for themselves. So the shift has been enormous.

Rainforest in the Colombian Amazon. Photo taken by Rhett Butler in March 2010. |

When I arrived there, most of the children went to missionary schools, which were teaching them not to be Indians: the language was wrong, the religion was wrong, the food was wrong—everything was wrong! But if you are like us, said the missionaries, everything will be right! So they were told the white people had an ideal world—so they all want to migrate.

Once they got the land, there was the first change. But it wasn’t enough. Then when they started building their own programs and participating in education, health, and land management, it got more interesting.

The Indians started hiring their own people for teaching and doing research. Some of these people started having a job and an income. And because they had a job, they produced their own food, they had their own transport, they built their own houses.

But then, through their way of doing research, the young people became more inspired in following the knowledge of the traditional people.

So they had broken the pull of the city. Before the young people had been separate from the elders, because the young people felt that the elders’ knowledge was not worthwhile. Instead they listened to the white people. And they, as young people, spoke Spanish and they thought they knew more than their elders.

But with the knowledge they got from the elders they could negotiate much better with the white people. Yes they could try to imitate the white people and negotiate with the white society on the white people’s knowledge where they were always inferior, or as they realized, they could negotiate on the basis of their own knowledge—their strong point.

Tikuna girl in the Colombian Amazon. Photo taken by Rhett Butler in March 2010. |

So suddenly their traditional knowledge—and therefore the elders—became important. The Indians became proud of their traditions and knowledge.

So they weren’t migrating when they were in the rubber camps, because traders didn’t let them. When they became free they started migrating because they were told that it was better to live outside. Once they got their land, their own government, and their own livelihoods, they stayed where they were.

Once that happened, they started moving forward. Now they are not migrating any more and the few that migrated are coming back, because they feel humiliated in our world. When they migrated to cities they were to poorest, faced discrimination, and didn’t have friends or a sense of belonging. They were on their own. So they come back.

As I mentioned, the indigenous territories are 25 million hectares, but we work in about fifty percent of that, which provides a good comparison. So we can see in the other area how people have migrated, or where miners are coming in because they don’t have organization or money be used properly for services.

So organization has brought stability for the indigenous and the government.

mongabay.com:

Is the Colombia government benefiting from the arrangement in that indigenous are running their territories so well?

MARTIN VON HILDEBRAND: Yes, for the government it is very good. For example, take education. Indian people do it for $700, which is half the price the government spends. For health, the cost is $20 per person per year. Why is it so cheap? Eighty percent of the cases are handled by indigenous doctors using indigenous medicine. The price comes down because it is more efficient.

Passion flower in the Colombian Amazon. Photo taken by Rhett Butler in March 2010. |

Indigenous medicine is preventive whereas Western medicine is expensive because we are not really preventing, other than vaccination, which is a very effective way of prevention.

And for the government it is very interesting because when it holds a meeting at the end of November, ever year, with the indigenous to draw up the plan for the next year, the indigenous can report exactly what is happening in their territory. This is good for government members, who can say “I have got my Department, my State, under control. I can tell you where the people are, where the money is going, what the Ministers are doing.” And that, for Colombia, a country with guerrillas and the paramilitary, is unbelievable!

We have an enormous area so to have a strong idea of how money is being used and the situation on the ground is powerful. It works because it is done by the Indians! We get the government on board because we spend half the money—the Indians are efficient and effective.

All of this is very empowering but we have to get them more independence. We cannot let the government put them under pressure—the Indians have to start putting the government under pressure about THEIR projects. So if we can get REDD or REDD+ money, the indigenous can start playing a bigger role and have their own source of money so they can depend less on the government for funding. REDD+ could work if it is properly done. If it is not properly done it could be a mess!

mongabay.com:

Colombia is going through a major transition now. It is going from a situation where a lot of the country was controlled by drug trafficking groups— paramilitaries and guerillas—to a place where those issues are becoming less important. So now a lot of people fear that there may be a rush for developing forests lands—perhaps indigenous lands—for mining, oil and gas, and maybe logging. Could you touch on the implications of this transition as well as the two pro-industry laws for forests and agriculture that were recently ruled unconstitutional?

MARTIN VON HILDEBRAND: Yes. What is happening in Colombia is a transition, undoubtedly. But this transition I don’t know to what extent is a real transition. I don’t believe it is that powerful, because the drugs are there. And as long as there are drugs in Colombia we will have corruption, we will have violence. Drugs are the basic problem in Colombia. And unless we somehow legalize drugs, I think we will have a problem for a long time—both national problems and international problems.

Danilo Villafañe, a political leader of the Arhauco people in northern Colombia. The Arhauco, a fiercely independent and deeply spiritual group that lives in the Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta Mountains in Northern Colombia, have for the past 30 years struggled against paramilitaries, guerillas, coca growers, and colonists who have invaded their lands for ranching, coca production, and racketeering. But today the Arhauco are making progress in their struggle, buying back farms and ranches, while eradicating coca fields. The efforts are paying off: today their Indian reservation extends from the high mountains of the Sierra Nevada nearly to the sea. Photo by Rhett A Butler, March 2010. |

It is very complicated and difficult to deal with—this is really financing the war. When we say that the FARC have been pushed back, it is true. They have, with better military equipment and a better-trained army, pushed the FARC back. We still have the paramilitary—we have not solved that problem. Yes, some of the leaders were caught and sent to the United States, but the basic people that are involved in the paramilitary are still involved.

Peace is much more solving the social and economic problems in the country rather than chasing off the guerrilla and paramilitary. You have to solve equity; you have to solve injustice; you have to solve the needs of the people as far as possible. But just stopping the fighting in Colombia will not solve the problems.

A lot of land has been taken away from the poor people by the paramilitary. I believe three million or more people that have been displaced and are now in cities. These problems are not being solved.

Now, it is true what you say about laws. Land laws have been put in place, especially for mining and securing prime investment. But a lot of laws are put in place also for the environment and a lot of laws are put in place also for human rights for indigenous people.

Now, we can choose: we can spend our lives from one sector to the other, taking each other to court, and we can win—we have good courts in Colombia—or we can get around a table and say, “Look, let’s fix this as a country. Let’s try to do our best to have a country for future generations; and let’s see how we can manage this country—from a mining point of view, from an oil point of view, from an environmental point of view, from the community point of view—and let’s try and work it out on reasonable terms.”

Clown tree frog (Dendropsophus leucophyllatus). Photo taken by Rhett Butler in March 2010. |

And this is the challenge; and that is what we are trying to do in the Amazon, although the Amazon is not as affected as the rest of the country. But I do think that, if we sit together and we start thinking about this seriously, aware of climate change, aware of the danger of future generations, aware of our responsibility, and with very high standards, we can come to something that works. If we don’t go for something like that, I don’t think we will get very far. I mean, the laws are there but we cannot spend our time taking each other to court and fighting each other. And I don’t know if we will get very far, because perhaps they will win now, we will win tomorrow; but if we are fighting each other, we are not really building.

And I think that the whole idea of the Colombian constitution is important because in 1991 we got a new constitution in which everyone participated: indigenous people, local people, the government. We all sat around the table and came to an agreement. And indigenous people play a big part.

Basically what the indigenous said is, “We accept the presence of non-indigenous people in this country, on the condition that we all respect each other. You respect our land, our rights, our culture and our future—and we will respect yours. And we will solve this in a good way, and we will work together to build this country. And we will do it together.”

And I think that is a big experience. It is not happening. It is taking time. The elite will not give up; they want to take your land—it has been difficult to put this into practice. But that is the basis of the whole constitution, of the social cortex: let’s build this country together, respecting one another and respecting the rights of each sector.

And then, if we all respect the constitution, I think we could come a long way. There are certain political structures out there that weaken the constitution and have to be revised; but otherwise I think the principles are very sound.

Big companies are coming in now obviously as Colombia is selling itself as a place where “We sell ourselves cheap; we get quick money” —and at the end we have a big hole!

And that is where we have to bring in international responsibility. So we have to deal with these companies—not just at a national level but at an international level. Let’s look at all these big companies. We have to start talking together and say, “How can we look at the future together?” And then we have to talk at an international level.

That is why we have all these meetings that we have set up now in the Amazon basin, looking across the entire region rather than just Colombia. We have to start looking at this governance and how we are going to handle it. We need certain laws; we need certain barriers, or certain limits, which have to be clear. I think if not we are just going to continue in a permanent conflict.

mongabay.com:

The “ley forestal,” a decree that would have opened up more land to development, was rejected two years ago because of the constitution and indigenous rights. In that case would you say the system is working?

MARTIN VON HILDEBRAND: Yes, that’s what I say. Our courts are strong.

This was a law to put through so private companies could have access to the forests in indigenous territories or to the primary forest. It was taken to court and thrown back, for not consulting these people, which under the constitution they have to do now. They need prior consent.

With the “ley rural” the same thing happened—although it was for the whole country. They were not consulted and the courts said that they were not now consulting them. There has to be pre-consent before you start a project.

Gold mining in neighboring Peru. Photo taken by Rhett Butler in October 2005. |

Right now, in the last two months, they stopped a large mining company in because they had not consulted the indigenous people properly. And they are very clear now; the court has said, “It is not just consulting. It is previous consent.” They have to consent to this period and they have to understand; they have to have all the studies, they have to explain exactly what is the impact.

The constitution says “Mining can be done on condition it does not undermine the culture, the economy or the environment where indigenous people live.” And you have to do all the studies: What is the impact? How is it going to undermine or not? What reasons could there be to prevent it? So there are a lot of conditions. And this has become stronger and stronger because the courts are insisting that it has to be properly done.

So that is why I am saying, “Are we going to spend our time in court? Or are we going to sit down and talk about this, and see how it can be done properly?”

mongabay.com:

When there is a court ruling, does the government have enough control over these areas to enforce it?

MARTIN VON HILDEBRAND: No. Monitoring is a big problem. It is the local people that monitor. It is the local people that come up and take these cases to court. But we are getting a bottom-up monitoring system.

mongabay.com:

Okay—you say there is this strong governance structure. So does this mean the indigenous communities which whom you work are more likely to be able to deal with these threats than in other parts of Colombia where there isn’t this structure?

MARTIN VON HILDEBRAND: That is absolutely true. And there are certain areas where companies are in strong—where there is a lot of money involved. These governance structures are very limited by paramilitary and by violence, as well. So it is complicated.

Again, we have to come to a point where we can talk about these things and not solve them with guns or courts.

mongabay.com:

Looking to the future, it sounds like you are fairly optimistic. What do you see as being the biggest challenges to working in the region, but also beyond to other parts of Colombia?

MARTIN VON HILDEBRAND: Well, if we are looking beyond, the biggest challenge is drugs. What can we do about drugs? Can we reduce the amount of drugs or not? That is one of the biggest challenges.

Woolly monkey in the Colombian Amazon. Photo taken by Rhett Butler in March 2010. |

The second biggest challenge in Colombia is institutions. I think that we have lost a lot of power. We only have good courts. We have a very high percentage of people in Parliament who are paramilitary politicians; and that has to be dealt with seriously. The government has been weakened—the Ministries have been weakened enormously because the government we have right now is very, very authoritarian, centralized, and is very controlled and everything. So our Ministries are very weak. Our judicial system is very weak—although the courts are strong.

It will take us some time to recuperate the country from an institutional point of view. It will take us time also to create awareness among people to use their rights and become democratic citizens—because they are under permanent pressure of rights and war.

There are big issues in the country—but much more than the economic problem. The economic problem really is corruption. I mean, if we distributed government funds properly, we wouldn’t need any extra money. I mean, obviously we would have to deal with the outside world for business—but it is not a major economic problem in Colombia.

Our area is considered post-conflict but the remains to be seen, because we will get a conflict if we don’t think properly. And in a lot of the Amazon region there is now a rush on mining.

We are saying, “We have to preserve the rainforest, we have to empower local people, we have to have local governance” —possible because these areas are pretty much unaffected there and there are mostly only indigenous. But with the mining coming in now, it is a different type of development. And so that is our major, business spurt right now in the Colombian Amazon. Is it possible to sit and talk with them? With large companies, yes. With the small companies—these are the most disruptive and chaotic. The government cannot monitor mining and cannot control it.

What can we do about that? Will they become cooperative and get organized in some kind of cooperative system and get the small mining under bigger mining control?

We have to look into other experiences in other parts of the world: of good practices. What did they do when they had to deal with small mining companies? You may be able to negotiate minimum standards for big companies to operate into the Amazon, but with small mining, how do you control those standards? So that is something we have to look into seriously.

mongabay.com:

Do you see deforestation threats beyond mining? What about large-scale agriculture—do you see that as much of an issue in the indigenous territory?

MARTIN VON HILDEBRAND: Not really a problem in a large way. There are some of the crops coming down but that can be dealt with.

Mining is a big problem. Mining tantalum, which is used for cell phones, is a surface activity that can spread out and cause a big impact. If mining involves roads then you can have colonization.

Tikuna man crossing a river in the Colombian Amazon. Photo taken by Rhett Butler in March 2010. |

But it is very complicated. If it involves large amounts of money then people will want to have roads or they will fly in and start all kinds of businesses around the mining. The amount of money coming into the mining can have a very big impact.

Now what happens if we get payment for standing forest through REDD or REDD+? Because if we had a strong income on standing forest on REDD+ it might make forests more useful to people than for mining. When small mining comes in and destroys the forest for a bit of money you might have others say, “Sorry but we are getting money from that tree—and that means money for us.”

Therefore we could get the local people involved in controlling and the government would be interested also. But we have to move with REDD+ and we have to move in the next couple of years. And we could start now, taking loans, hoping that it will come in and we will be able to pay it back. But that is one possibility.

mongabay.com:

You are doing good things that are going well in Colombia, but if we want to look at the broader problems in the world, are there things that you can take away from the indigenous mindset to change consumption patterns and the way we view the world, in order to address things like climate change and other environmental problems?

MARTIN VON HILDEBRAND: Well there are certain things we can take from them, undoubtedly. Not just practical things—because we have so many things from them already, like food and medicines. But let’s say when it comes to protecting the environment, they take different approach, which is called in the West “The Sacred sites”. So you have key sites, key points in nature, which are important for life; for the whole system of life.

It is a bit like acupuncture. Their attitude toward the planet is a bit like acupuncture; so take it to a point and then control the use of the forest according to the different seasons; how to use it to keep the energy flowing through these key points.

So it is looking much more at how to keep the system healthy than how to leave the parts, shall we say, “hands-off.” So this covers a large ecosystem. We are working on that approach and learning.

We have already set up a Park in Colombia, a national park, which is run by indigenous people and is introducing these new concepts.

I think from the social structure, and from the economy lessons can be learned. And it is interesting to see how they have this economy where all the surplus is to strengthen the relations between people and the communities, and not to accumulate with the individual.

Von Hildebrand at Oxford University in March 2010. |

So there are many things we can learn from these people of course. But the problem is our drive, our economic drive, our individualistic drive, our urban drive: to what extent will it allow us to use these teachings? To what extent are they practical? And when we are concentrated in big cities and we are so dependent on food coming in from the outside; and where we are so competitive and individualistic.

But undoubtedly, all these other cultures, that have evolved for thousands of years just as much as we have, and have a profound knowledge of the environment and an understanding of the world. Obviously there is a lot to learn from them—since all we have to do is open a newspaper to see that our own world is a mess. Perhaps we SHOULD start listening and see how they understand the world and how they think it should be done.

We can certainly learn about nature, medicinal plants, food—many opportunities that are in the forest; ways of understanding nature; and how to adapt. I think the people that are closest to nature will probably adapt better to climate change than those of us most of us who are unnerved the moment we don’t have electricity or access to a supermarket. So perhaps they are the final survivors. Although we think they are primitive.

Related articles

Indians are key to rainforest conservation efforts says renowned ethnobotanist

(10/31/2006) Tropical rainforests house hundreds of thousands of species of plants, many of which hold promise for their compounds which can be used to ward off pests and fight human disease. No one understands the secrets of these plants better than indigenous shamans -medicine men and women – who have developed boundless knowledge of this library of flora for curing everything from foot rot to diabetes. But like the forests themselves, the knowledge of these botanical wizards is fast-disappearing due to deforestation and profound cultural transformation among younger generations. The combined loss of this knowledge and these forests irreplaceably impoverishes the world of cultural and biological diversity. Dr. Mark Plotkin, President of the non-profit Amazon conservation Team, is working to stop this fate by partnering with indigenous people to conserve biodiversity, health, and culture in South American rainforests. Plotkin, a renowned ethnobotanist and accomplished author (Tales of a Shaman’s Apprentice, Medicine Quest) who was named one of Time Magazine’s environmental “Hero for the Planet,” has spent parts of the past 25 years living and working with shamans in Latin America. Through his experiences, Plotkin has concluded that conservation and the well-being of indigenous people are intrinsically linked — in forests inhabited by indigenous populations, you can’t have one without the other. Plotkin believes that existing conservation initiatives would be better-served by having more integration between indigenous populations and other forest preservation efforts.