A debate rages in India over a proposal to ban tiger tourism in India. Proponents of the ban say tiger tourism is intrusive and disturbs tigers and wildlife in tiger reserves. Opponents say that among all the threats to the tiger, tourism is the least potent and raises awareness. Shubhobroto Ghosh weighs in on the issue after seeing his first wild tiger in the flesh.

I have always been uncomfortable when friends and colleagues, especially from abroad asked me if I had seen a tiger in the wild because I had not. Well, I will not be anymore. For on 11th December, 2009, at 4.30 pm I saw my first wild tiger at Kanha National Park in Madhya Pradesh where I was attending a training programme for senior forest and police officers with office colleagues.

We went on a park drive as soon as we arrived on 11th December and one hour of the most intensive searching did not reveal anything. And just when I had given up hope and we were completing the last round of the tour, the king of the Indian jungle was spotted in a ravine in Salghat Charia in Kisli Range. He could not be clearly seen initially. But we stayed put and then he walked out on the trail right in front of our jeep, barely ten feet from where we were stationed.

The tiger is an animal that does make me speciesist, at least momentarily. The Giant Panda is cuter, the Pygmy Hog more endangered, the Snow Leopard more elusive, the Leopard perhaps more difficult to spot and Great Apes more interactive. But the tiger is simply the tiger in terms of sheer glamour and appeal and when the animal walked out in the open, it was a feeling unlike any other I have ever experienced, it was so thrilling.

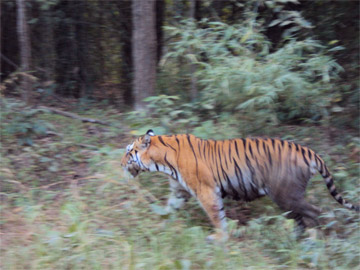

Wild tiger in Kanha. Photo by M K S Pasha |

My first wild tiger! Panthera tigris. The consort of Santoshi Maa, one of the most revered figures in Hindu mythology. Rudyard Kipling’s villainous Sher Khan. Jim Corbett’s large hearted gentleman. Billy Arjan Singh’s controversial hybrid Tara. Saroj Raj Chaudhuri’s beloved Khairi. The animal the World Bank wants to save. The target of the entire poaching community. George Schaller’s subject of study in 1965 in Kanha National Park. William Blake’s inspiration for his immortal poem. The subject of endless discussion and debate among conservationists, animal rights activists and animal welfarists. India’s national animal that has now become a symbol of conservation worldwide.

But when you first view the animal, these thoughts do not occur at all. You are struck speechless by the sheer beauty and grace of the animal. The animal I saw initially was a large male in prime condition, and he was visible for half an hour flat. He ambled down the road, followed and preceded by our jeep and several others. He marked his territory and went inside a thicket several times, only to re emerge. I was literally trembling with emotion when I first spotted him, so great was my excitement. Several scores of photos and minutes of video filming later, he vanished as mysteriously as he had appeared. The King of the Indian forests had finally condescended to grant me a sighting. The forest guards were tipped handsomely for all their help after the trip by my colleagues and me.

Later on, we saw another tigress in another area but the first sighting is the one that will remain embedded in my memory till the day I die. I must have seen several hundreds of zoo and circus tigers, but these two animals were incomparable to anything I have seen before.

We saw several other species, Gaur, Jackal, Sambar, Cheetal, Langur, Peafowl, Paradise Flycatcher, Kestrel, Shikra, Barred Jungle Owlet and Spotted Munia among others but the Tiger captured the show for the entire duration of my stay in Kanha. Even as I write this note, I feel a tingling sensation of awe and wonder at having seen such a marvel of evolution. A sensation only comparable to the beauty of a starlit night that continues to stupefy me. A sensation that makes you feel that animals are worth saving for what they are, and not for what we can get out of them.

Male tiger in Kanha. Photo by M K S Pasha |

A live animal makes you respect the process of evolution and pay attention to their habitat, for the Kanha forest is as beautiful as a cathedral, especially when light filters in through the massive sal trees. And I can do no better to end this note than share a quote with you by the American ornithologist William Beebe, that repeatedly struck my mind during nights at Kanha : “The beauty and genius of a work of art may be reconceived, though its first material expression be destroyed; a vanished harmony may yet again inspire the composer; but when the last individual of a race of living beings breathes no more, another heaven and another earth must pass before such a one can be again.” (The Bird (1906).

When I left Kanha today morning, I bowed once before entering the vehicle. Expressed my gratitude to the gifts of organic evolution and hoped that the rolling greenery of this marvellous national park, one of the best maintained in Asia, would always be a home to the most regal denizen of the Asian wilderness.

Shubhobroto Ghosh is a former journalist for the Telegraph newspaper whose work has also been published in the Times of India, Telegraph, Statesman, Asian Age, and the Hindu. Ghosh has been active in animal protection issues since the early nineties and is a member and supporter of several animal organizations, among them Durrell Wildlife Conservation Trust, Born Free Foundation, People For Animals and Beauty Without Cruelty. He has worked at the Wildlife Trust of India, was project coordinator for the Indian Zoo Inquiry project sponsored by Zoocheck Canada, and did his Masters thesis on British zoos.