Following a damning report from the Rainforest Action Network (RAN) alleging illegal clearing of rainforest in Indonesia by agriculture-giant Cargill, activists have infiltrated Cargill headquarters in Wayzata, Minnesota and refuse to come out until the CEO agrees to meet with them. According to local reports, five activists are locked inside a staircase, while others are protesting outside the building.

Yesterday, RAN released an investigative report, Cargill’s Problems with Palm Oil: A Burning Threat in Borneo, on Cargill’s actions in Indonesian Borneo that included some surprising revelations about the number one importer of palm oil in the US. In the report, RAN alleges that Cargill is currently holding two undisclosed palm oil plantations in western Kalimantan, which are actively clearing rainforests and destroying peatlands.

A member of the Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil (RSPO), a group that is working toward setting sustainable guidelines for the palm oil industry, Cargill said in a public statement that RAN’s report was false.

|

“We do not have a set of plantations that are hidden from the public where we are doing things we would not do in public at the plantations we clearly own and operate,” said Lori Johnson, a Cargill spokeswoman, as reported by the Minneapolis Star Tribune.

Yet field investigations and interviews by RAN and local NGO, Kontak Masyarakat Borneo (KMB), found that Cargill subsidiary, CTP Holdings, operated two undisclosed palm oil plantations, which it has not revealed publically, to the Indonesian government, or to RSPO. According to RAN both of these plantations lack business permits, location permits, and timber cutting permits.

The larger of the two plantations, estimated at 15,000 hectares, has had 10,500 hectares of rainforest cleared since 2005, an area larger—according to RAN—than all four of the Walt Disney theme parks. The report also states that this palm oil plantation is actively destroying carbon-important peatlands. In addition, locals in the area say that the palm oil plantation has cleared tribal lands without their permission. Since these palm oil plantations don’t exist on paper, they are actively spurning both Indonesian law and RSPO requirements.

“Cargill is trying to have their cake and eat it too,” said Leila Salazar-Lopez of RAN in a press release. “While Cargill is proclaiming their commitments to RSPO standards, they’re going ahead and doing whatever they want to rainforests, waterways and community lands.”

Peat forest conversion in Kalimantan, Indonesian Borneo. Photo by: Rhett A. Butler. |

RAN accuses Cargill of also violating Indonesian law by using fire to burn its plantations and possessing palm oil plantations that exceed the maximum allowed concession area.

This isn’t the first time Cargill has been under fire for its palm oil policies. As well as operating its own plantations, Cargill currently sources palm oil from known environmental offenders like Indonesian-company Sinar Mas, which has recently been dropped by both Unilever and Nestle due to continuing environmental concerns. A Greenpeace campaign is currently targeting Nestle, because it is unwilling to cut ties with Cargill and thereby indirectly sources Sinar Mas palm oil.

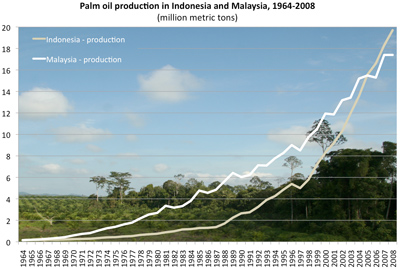

As the highest-yielding commercial oil seed, palm oil is a cheap vegetable oil used in everything from soap to cosmetics to a large number of food-products. Yet, its environmental impacts in countries like Indonesia and Malaysia have been huge, including biodiversity loss in some of the world richest rainforests, conflict with indigenous groups who depend on the forests for their livelihood, and sizeable greenhouse gas emissions. Currently, Indonesia is the world’s third largest greenhouse gas emissions, yet unlike industrial behemoths China and the US, Indonesia’s emissions are largely due to deforestation and peatland destruction.

“Cargill’s palm oil is everywhere in U.S. grocery stores,” says Salazar-Lopez. “If you buy consumer products that contain palm oil, it’s likely that you’re buying Cargill’s palm oil made from rainforest destruction. And, if you’re a Cargill palm oil customer, you’re being lied to about where your palm oil is coming from.”

Cargill has since strongly refuted the charges leveled at it by RAN’s report. They have released a statement to ‘set the record straight’ where they address the strongest allegations one-by-one: Cargill sets the record straight on the false allegations made by RAN in its May 2010 report.

Related articles

Commodity trade and urbanization, rather than rural poverty, drive deforestation

(02/07/2010) Deforestation is increasingly correlated to urban population growth and trade rather than rural poverty, suggesting that measures proposed to reduce deforestation will be ineffective if they fail to address demand for commodities produced on forest lands, argues a new paper published in Nature GeoScience.

Cargill sells palm oil business in Papua New Guinea

(02/26/2010) Cargill will sell off its palm oil holdings in Papua New Guinea (PNG) to focus on operations in Indonesia, reports the Star Tribune. The $175 million sale involves 62,000 ha of oil palm across three plantations and several mills.

Palm oil developers in Papua New Guinea accused of deception in dealing with communities

(09/25/2009) Papua New Guinea, the independent eastern half of the world’s second largest island (New Guinea), houses one of the planet’s last frontier forests. These forests support a wealth of plants and animals as well as the Earth’s most diverse assemblage of cultures—some 830 languages are spoken in Papua New Guinea (PNG), representing more than 12 percent of the world’s 6,900. But PNG’s forests are fast-changing. Between 1972 and 2002 PNG lost more than 5 million hectares of forest, trailing only Brazil and Indonesia among tropical countries. Forest loss has been primarily a consequence of industrial logging and subsistence agriculture, but large-scale agroindustry—especially development of oil palm plantations—has emerged as an important new driver of land use change. Dozens of international companies have set up operations in the country over the past decade, including Cargill, an agribusiness giant based in Minneapolis. While Cargill says it is committed to sustainable and responsible palm oil production across its three plantations in PNG, the firm has been targeted by local and international NGOs, which claim it has polluted rivers and deceived local communities into signing agreements they do not understand. Some landowners say they are receiving few of the benefits oil palm promised to deliver, while losing their independence—they are now reliant on an export-oriented crop they can’t eat. Opposition to further oil palm expansion is now growing, especially in Oro Provice, where Cargill’s plantations are based.