The first in an interview series with participants in the 5th Frugivore and Seed Dispersal International Symposium.

There are few areas of research in tropical biology more exciting and more important than seed dispersal. Seed dispersal—the process by which seeds are spread from parent trees to new sprouting ground—underpins the ecology of forests worldwide. In temperate forests, seeds are often spread by wind and water, though sometimes by animals such as squirrels and birds. But in the tropics the emphasis is far heavier on the latter, as Dr. Pierre-Michel Forget explains to mongabay.com.

“[In rainforests] a majority of plants, trees, lianas, epiphytes, and herbs, are dispersed by fruit-eating animals. […] As seed size varies from tiny seeds less than one millimetre to several centimetres in length or diameter, then, a variety of animals is required to disperse such a continuum and variety of seed size, the smaller being transported by ants and dung beetles, the larger swallowed by cassowary, tapir and elephant, for instance.”

Pierre-Michel Forget at Nyungwe National Park in Rwanda. Photo courtesy of: Pierre Michel Forget. |

Forget, a French tropical ecologist, is chairing the 5th Frugivore and Seed Dispersal International Symposium held in Montpellier, France from June 13-18th. Forget has studied the relation between seeds and fruit-eating species both in South America and Central Africa, focusing mostly on mammals.

“Indeed, when you observe the understory and see that profusion of seedlings, it is not always obvious that there is some type of order, seedlings being not really randomly dispersed, rather directed-dispersed at some peculiar microhabitats,” he says.

Yet, the species so important to successfully spreading tropical seeds are also some of the most threatened. Their decline—and in some case absence altogether–spells a fall in forest richness.

“If you consider large-bodied, plant-dependent and seed-dispersing animals, they are all threatened by hunting, deforestation, fragmentation, mining, dam and road construction,” Forget says. “Many of fragmented forests, even some natural parks and reserves, now lack the large ungulates, primates and birds that disperse seeds. Extinction is sometimes very recent due to uncontrolled development of large-scale agriculture, poaching and logging.”

Forget points out that when it comes to seed dispersers it’s not global extinction that one must focus on, but local extinction and even a decline in wildlife abundance.

“If spider monkeys are protected in a remote forest of the Peruvian Amazon, it won’t help much those trees of French Guiana,” he says. “Additionally, when large frugivores are exterminated, because it’s also an important source of protein for native people inhabiting rainforest, we are also endangering survival of autochtonous populations. And that has to be considered in conservation plans. Not only will we lose natural diversity, but humanity will also lose cultural diversity.”

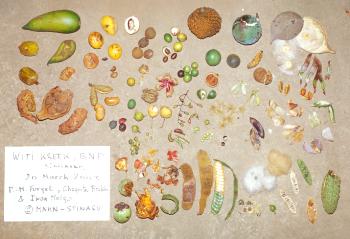

Tropical fruits and seeds. Photo courtesy of: Pierre-Michel Forget. |

Forget argues that to date the role of seed dispersers has largely been left out of conservation discussions, even though these species’ actions underpin entire ecological communities. According to Forget, the current focus on the conservation of pollinators—such as bees—tells only part of the story.

“Now that stakeholders recognized the important ecological role of bees for the pollination of flowers and the production of fruit, they must now acknowledge that without frugivores, those crops will remain in tree crown, fall to the ground, and rot without primary and secondary seed dispersers. It’s a waste of carbon for the ecosystems. Thus, saving the bees from extinction is only half of the work done,” he says.

Currently the most threatened seed dispersers are the largest ones: elephants, tapirs, primates, large birds and bats. These big-bodied frugivores are also the most responsible for moving the tropical forest’s big seeds. Yet with the decline in these frugivores, Forget sees a corresponding decline in the forests’ ability to store carbon.

“Because the small-seeded plant species are often those that stock less carbon, then such secondary, depauperate forests [i.e. forests that have lost big-bodied frugivores] may lose their important role as carbon sink. Therefore, there might be a direct link to establish between the impact of the extinction of frugivores species in rainforest, and other forests as a whole, and climate change,” he says.

Central American agouti (Dasyprocta punctata) is a large seed specialist: due to specialized handling skill this rodent is able to eat, bury and cache large seeds few other species can. Photo courtesy of Pierre-Michel Forget. |

“The life cycle of biodiversity must be complete from the adult plant to the next generation, and this is mainly done in tropical and temperate forests by frugivores and seed dispersing animals that allow seeds to become young established plants, and to store carbon,” Forget adds. “It is one more good reason to save dispersing species, and not only because these are big and charismatic, but simply because they offer an important ecological service by dispersing seeds, and contribute to carbon storage in established plants. Imagine how much it will cost to plant all these acorn trees in the nature when jays and squirrels can do it for free.”

There is no question that issues such as these will be discussed widely and passionately at the 5th Frugivore and Seed Dispersal International Symposium in Montpellier this summer.

|

“We are expecting to have several generations of ecologists from the entire planet attending the symposium, and most of all former FSD organizers. It’s like a big family dispersed across countries and continents that travel and meet once every 5 years, and though aging, we are also bringing our ‘kids’, the future generation, our PhD students, the future leaders,” Forget says enthusiastically, adding that currently scientists from 28 countries are attending. He says that while virtual meetings are important, they “will never replace the experience of a human-rich meeting”.

In a March 2010 interview mongabay.com spoke with Pierre-Michel Forget about the ecological importance of frugivores, the myriad threats to these species, and the upcoming symposium to address both the science and the conservation of the world’s seed-dispersers.

INTERVIEW WITH PIERRE-MICHEL FORGET

The fruit and seed of the Virola kwatae. Photo courtesy of Pierre Michel Forget. |

Mongabay: What is your background? How did you become interested in seed dispersal?

Pierre-Michel Forget: I am a forest ecologist, especially interested in animal-plant relationships and dynamics of commercial timber species and other species that are source of Non-Timber Forest Products. When I started my PhD project on tree recruitment in French Guiana in 1984, I decided to focus on several key timber species that illustrate a diversity of modes of seed dispersal, from the least to the most efficient in term of distances of dispersal of propagules away from the parent trees, dispersal effectiveness being often dependent on seed size, the smallest diaspore being dispersed the farther.

Whereas other botanists would have been interested in the abundance and diversity of plants and life-history traits of seedlings in term of survival and growth, as a generalist ecologist I was rather questioning how plants move in the rainforest, and how far they go. I thus decided to investigate several tree species which seeds are dispersed either by gravity – that is not really dispersal per se – wind, or projection, or transported by animals such as rodents, bats, primates or birds. My principal quest and interest from a naturalistic point of view was to illustrate how abiotic and biotic factors affect the final spatial pattern of seedling and juveniles.

Indeed, when you observe the understory and see that profusion of seedlings, it is not always obvious that there is some type of order, seedlings being not really randomly dispersed, rather directed-dispersed at some peculiar microhabitats, and that their dispersal kernel follow some natural laws that are tightly related and dependent on seed life-history traits such as size. The mode of dispersal of plant is also dependent on the occurrence of pulp or fleshy parts that may surround seeds when inside the fruit, the attractive bait for frugivores, the seed dispersers.

Later, during my post-doc period at the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute in Panama, walking in the steps of my Ph D advisor (Gérard Dubost) who was studying the ecology of acouchy and agouti in French Guiana, I experimented and analysed the role of those large rodents as both predators and dispersers when the scatterhoard seeds that they will later consume, though some might be forgotten, and establish as seedling. Since then, I navigated across all modes of dispersal and their consequences for seedling recruitment, with a special interest in plants dispersed by mammals, from the smaller such as spiny rats in French Guiana to the largest such as elephant in Central Africa.

Mongabay: How did you come to be in charge of 2010’s Frugivore and Seed Dispersal symposium?

The spiny rat is an important seed predator as well as seed disperser in South America. Photo courtesy of Pierre-Michel Forget. |

Pierre-Michel Forget: Well, it’s a long story. In São Pedro, Brazil, during the last evening of the 3rd FSD symposium, given that we already knew that FSD will go to Brisbane, Queensland, Australia in 2005, I had a discussion with Eugene (Geno) Schupp, who was teasing me to organize the symposium in Sevilla in 2010! Who would think 10 years in advance beside people who are applying to organize the Olympic Games! This 5-year FSD symposium is our Olympiads, and we have our own valued medals, the David W. Snow award, for the best oral and poster papers by students.

I was very much interested in going to Sevilla where there is a fantastic group of colleagues who study frugivores and seed dispersal in diverse habitats at all latitudes and longitudes. During the evening, while musicians were playing brazilian songs, Pedro Jordano, Philip Hulme, Anna Traveset and myself took the important decision to have the Symposium organized in Sevilla in 2010! Geno had planted the seed, and it rapidly germinated and took root in my brain.

Then, in July 2005, at 4th FSD Symposium in Australia, toward the closing ceremony I was however asked by former organizers to take the lead in France, instead of Spain. By that time, I just finished to edit and published with some other frugivores-addicts the CABI-edited book SEED FATE; my colleagues thus thought I could be the man for the next FSD. Although I was about to chair the Annual Meeting of The Association for Tropical Biology and Conservation (ATBC) in Paramaribo, Suriname to be held in 2008, I however accepted the unanimous vote of the participants to go to France in 2010. I felt very proud for my country, and thus accepted to organize it in Montpellier not knowing what a challenge it will be. Thus, while I was flying back to France and then to Brazil to attend the ATBC Annual meeting in Uberlandia – I will then be elected President (2007-09) of the ATBC – I already had two major international meetings on my agenda to organize and chair, enough to occupy me for the next 5 years.

Mongabay: What are you most excited about in this year’s symposium?

The world’s biggest seed disperser. The forest elephant is vital species for the diverse ecology of Central African rainforests, yet it is heavily threatened by forest loss and poaching. Photo courtesy by: Rhett A. Butler. |

Pierre-Michel Forget: The organization of such a big symposium by only one person is rather impossible, and it’s a real scientific adventure that is performed by a group of people. The challenge here was to organize it with colleagues that were dispersed over the planet, and not present in Montpellier. But the city is only three and a half-hours from Paris, and I have good colleagues on site at CEFE-CNRS, the University of Montpellier and at CIRAD. The most exciting part was to interact with the academic and organizing committee members, and to assemble a diversity of plenary speakers and symposium with people coming from the whole planet, as far as New Zealand, French Polynesia or Hawaii, at least far from my location, Paris.

This has been possible in a reasonable amount of time thanks to the internet, working late when Western people will still be active, or early in the morning when Eastern colleagues will be starting their working day. Since the first FSD events, internet has developed to a point that we can now even have the symposium accessible on line for many of our colleagues – it’s expensive though, and we are seeking for a 8000 € grant to support it to allow scientists to virtually be at FSD – especially those from countries with low income, who are dispersed over the planet, and are unable to attend for financial, or logistical reasons.

Therefore, the symposium already existed on the web since July 2008, and has already been used to promote and share information about frugivores and seed dispersal with visitors, not necessarily scientists, but certainly many educators and scholars. Meanwhile, thanks to our Webmaster, I developed and edited FSD2010.org that presents each month some of the organisms FSD participants are studying, and how important these fruit-eating animals are for plant diversity and its maintenance in all ecosystems of the Earth. I also used the web to introduce the scientists to a broader audience of the web visitors, especially the younger generations, current and future leaders who should be as famous as rock stars and cinema actors. Indeed, they are incredible people who do an amazing job in the wild. Every kid wants to be a naturalist, an ecologist, in short a scientist.

SEED DISPERSAL AND TROPICAL ECOSYSTEMS

Mongabay: Why are seed dispersers so important to tropical (and temperate) forests?

A fruit specialist: the great hornbill flying in the forests of Thailand. Photo courtesy by: Rhett A. Butler. |

Pierre-Michel Forget: When a seed is not adapted to resist to pathogens, fungi, insects or seed-eaters with toxic compounds for instance, it may rapidly die lacking primary dispersal in the canopy and secondary dispersal after falling to the ground beneath the parent plant. Therefore, plants evolved strategies to attract consumers and be dispersed by them, insuring their survival away from the proximity of parent, which is a cause of high mortality for both seeds and germinating seedlings. This has been generalized by Dan Janzen and Joe Connell in 1970 and 1971, two major leaders for many scientists of my generation, not yet 50!

The attractive plant part for frugivores is often a pulpy component of the fruit, if not the entire fleshy fruit, or the propagule itself such as oak acorn carried away by a Jay or a Squirrel, for instance. When an animal consumes fruit or seeds they may either drop them beneath the parent, store it in cheek pouches and spit seeds, or swallow and defecate them later while foraging and moving across habitats. Therefore, the community of seed dispersers is a life insurance for plants in various ecosystems. This has an ecological cost however, and many of seeds are lost to predators, among them invertebrates such as moths or bruchids, or vertebrate such as deer, wild boar or peccaries, during and after the dispersal process. Nonetheless, the greater the richness of the seed disperser coterie, the better the dispersal of plants, especially in tropical forests. There, a majority of plants, trees, lianas, epiphytes, and herbs, are dispersed by fruit-eating animals. Contrarily to the temperate habitats, dispersal by wind, projection or water is only employed for a limited percentage of tropical plants. As seed size varies from tiny seeds less than one millimetres to several centimetres in length or diameter, then, a variety of animals is required to disperse such a continuum and variety of seed size, the smaller being transported by ants and dung beetles, the larger swallowed by cassowary, tapir and elephant, for instance.

Mongabay: What are some of the key species involved in seed dispersal?

A flying fox in Madagascar. Flying fox carry seeds far from parent trees. Photo by: Julie Larsen Maher. |

Pierre-Michel Forget: I would not say that there are key species of seed dispersers. All seed dispersers are crucial for plants, but the importance of their role may differ between plants. One small vertebrate may be a key disperser for a given small-seeded plant, and a negligible factor for another large-seeded plant, or even have a negative role when fruit are consumed and the large seed dropped when too large to be swallowed. Instead, I would comment that a plant needs at least one efficient seed disperser to help it moving and surviving away from the parent neighbourhood. For instance, Apes and other Primates, Elephant, Hornbill and Toucans are certainly some of the most charismatic, key species for many plant species in all tropical continents where they accomplish a very good job at dispersing an immense diversity of seeds while ingesting fruit, their main staple resources to survive themselves. For instance, some trees that belong to the nutmeg family are known to be highly dependent on Atelidae and Toucans for their dispersal in America, and Cercopithecidae, Bats, and Hornbills in Africa and Asia. Whether Primates may disappear (due to hunting or deforestation, for instance), then birds and/or bats may continue to partially fill this ‘transportation’ role, though the pattern of dispersal will be altered, modified, because because flying frugivores do not forage as arboreal ones, henceforth changing the chance to establish and survive in the most favourable habitats for which life-history plant traits have been selected.

After decades of studies on seed dispersal by animals, we are still ignorant about which seed-dispersing species are obligatory dispersers for the survival of many plants. The development of the Network theory may contribute to evidence when and which frugivores are essential, key dispersers for plants.

Mongabay: What will rainforests look like if seed dispersing species continue to decline in abundance?

Pierre-Michel Forget: It depends on the number of interactions –links – that exists between plants and frugivores. Considering the network of those interactions, if one plant is connected to several dozens of in/vertebrates, for instance, then losing one out of several frugivores or seed disperser species may not dramatically affect its survival, at least would certainly modify its dispersal kernel, and spatial recruitment pattern. Alternatively, consider one plant that is entirely relying upon one or two species, such as for instance the Brazil nut and Andiroba trees in the Amazon which are both dependent on scatterhoarding rodents for their dispersal. Surely, the extinction of such large rodents (> 1 kg) that are sensible to habitat disturbance and hunting would lead to the lack of recruitment on the short term, and the extinction of the tree species after decades unless humans plant seeds, as Amerindians used to do, or protect and conserve the fauna in Natural Reserves.

A dung beetle in Suriname. Dung beetles disperse tiny seeds. Photo by: Rhett A. Butler. |

There is an open debate about what the tropical forest will become lacking seed-dispersing frugivores. Based on my personal studies on large seeds dispersed by rodents, primates and birds, I believe that many species with small-to-medium sized seeds will survive very well, and will dominate in these half-defaunated forest lacking large-bodied frugivores, not yet empty habitats as there are always some resilience with many small-bodied frugivores that may develop in empty niches left by others, and somehow benefit from having more resources available once larger consumers disappeared. Such secondary forests are not those growing after deforestation or clearing, but are primary forests that lost their key dispersers, often easy targets for hunters, and consequently large-seeded plants that are not anymore ingested and dispersed. And because the small-seeded plant species are often those that stock less carbon, then such secondary, depauperate forests may lose their important role as carbon sink. Therefore, there might be a direct link to establish between the impact of the extinction of frugivores species in rainforest, and other forests as a whole, and climate change.

Mongabay: How would you characterize the state of seed dispersing species worldwide?

Pierre-Michel Forget: If you consider large-bodied, plant-dependent and seed-dispersing animals, they are all threatened by hunting, deforestation, fragmentation, mining, dam and road construction. Many of fragmented forests, even some natural parks and reserves, now lack the large ungulates, primates and birds that disperse seeds. Extinction is sometimes very recent due to uncontrolled development of large-scale agriculture, poaching and logging.

Let’s take the Nyungwe National Park in Rwanda where the last elephant was killed in 1999, and that I have visited. How the forest diversity of this unique mountain forest will evolve is not yet known, but is questionable. The Natural Reserve of Kaw in French Guiana has few spider monkeys left, and Virola kwatae (Myristicaceae) trees are mostly dispersed by toucans now. What are the consequences for surviving trees? The spider monkeys remained elsewhere as at Nouragues Natural Reserve but for how long? All these tropical forests are now highly impacted by gold-mining activities that is often associated with hunting. These frugivores and trees are thus highly endangered even though large populations remain elsewhere. The problem is rather local, and it’s locally that we must also consider the conservation of seed dispersing species, as well as that of their food resources, the diversity of plants upon which they depend year after year. If spider monkeys are protected in a remote forest of the Peruvian Amazon, it won’t help much those trees of French Guiana. Additionally, when large frugivores are exterminated, because it’s also an important source of protein for native people inhabiting rainforest, we are also endangering survival of autochtonous populations. And that has to be considered in conservation plans. Not only will we lose natural diversity, but humanity will also lose cultural diversity.

Mongabay: What conservation efforts or environmental laws would you recommend to save seed dispersing species?

The red-faced spider monkey Ateles paniscus at Nouragues National Reserve, French Guiana. Primates are important seed-dispersers worldwide, however they are also one of the most threatened groups of species. Nearly half are threatened with extinction. Photo by Sean McCann (2010). |

Pierre-Michel Forget: Now that stakeholders recognized the important ecological role of bees for the pollination of flowers and the production of fruit, they must now acknowledge that without frugivores, those crops will remain in tree crown, fall to the ground, and rot without primary and secondary seed dispersers. It’s a waste of carbon for the ecosystems. Thus, saving the bees from extinction is only half of the work done.

The life cycle of biodiversity must be complete from the adult plant to the next generation, and this is mainly done in tropical and temperate forests by frugivores and seed dispersing animals that allow seeds to become young established plants, and to store carbon. It is one more good reason to save dispersing species, and not only because these are big and charismatic, but simply because they offer an important ecological service by dispersing seeds, and contribute to carbon storage in established plants. Imagine how much it will cost to plant all these acorn trees in the nature when jays and squirrels can do it for free. It’s the same reasoning in tropical habitats. Thus, if we want a cool climate in the future, at least not a warmer one, we must rapidly think to conserve many frugivores in our forested habitats, and we won’t lose plant species diversity.

Mongabay: Will you tell us about some of your most exciting discoveries coming out recently?

Pierre-Michel Forget: My most exciting discoveries are not really new now, but are still feeding the news in our research field 20 years later. In fact, there are two main discoveries that were made early in my career. One was to match the seedling shadow of a large-seeded nutmeg tree (V. kwatae, a new species named after the spider monkey Ateles paniscus that disperse it seeds) with the movements of primates in the canopy. For that, I waited for days under fruiting trees awaiting spider monkeys, and then followed them after they left trees. It’s then by comparing my map of seedlings scattered on a large plot 180 m long by 25 m wide, and the route used by monkeys between tall trees that I have been able to suggest a direct link between seed dispersal by primates, and the final seedling spatial pattern, though some seeds might have been locally re-dispersed by terrestrial animals. Indeed, and that is my second most important discovery, for the first time in tropical rainforests, I have been able to illustrate that large (> 20-30 mm in length) seeds primarily dispersed by flying or arboreal vertebrates such as bats or primates might also be secondarily dispersed, namely scatterhoarded (e.g. cached) by either small spiny rats or larger ones such as Agoutis or Acouchies, therefore protected from predators if not recovered and eaten by hungry rodents or other seed-eaters or infested by insects.

THE FRUGIVORE AND SEED DISPERSAL SYMPOSIUM

Mongabay: What makes this year, 2010, especially relevant for meeting about the importance of seed dispersing species?

Red-tailed squirrel (Sciurus granatensis) feeding on a flower in Costa Rica. Squirrels are important seed dispersers both in tropical forests and temperate. Photo by: Rhett A. Butler. |

Pierre-Michel Forget: In 2010, there is a conjunction of events which makes FSD so exciting. Most importantly, it is the year of Biodiversity, and it is especially fitting with our theme and general interest. As I already mentioned, bees and pollination has been presented as a key ecological process for the sustainability of biodiversity, but we may not forget that without frugivores and seed dispersers, those fruit crops will vanish in natural habitats with dramatic consequences for the structure of the habitats: losing plant diversity, likely with feedback effect for pollinators, that also include many vertebrates such as bats. Thus, this year, I hope that the public will understand that the integrity of a whole forest, either tropical or temperate, or a savannah, is highly dependent on both pollination and seed dispersal, one goes with the other, and both are tightly linked. When pollinator and disperser populations decline, that of seed predators increases. A good ratio is thus needed between the good and the bad partners to maintain the fragile equilibrium of dynamics in natural ecosystems.

Mongabay: What are you expecting from this year’s symposium?

Pierre-Michel Forget: We are expecting to have several generations of ecologists from the entire planet attending the symposium, and most of all former FSD organizers. It’s like a big family dispersed across countries that travel and meet once every 5 years, and though aging, we are also bringing our ‘kids’, the future generation, our PhD students, the future leaders. It’s a very optimistic symposium, although the fate of frugivores and the biodiversity in natural habitats might be sad, even depressing sometimes when looking at the threats exerted on them, and the risk of massive biodiversity extinction.

Mongabay: Who will be at the symposium? What countries will be represented?

A Central American Agouti speeding off to bury its seed. Photo courtesy of Pierre Michel Forget. |

Pierre-Michel Forget: All leaders of the disciplines will be present, those from the 70s until today. They all accepted without hesitation to contribute with plenary talks, and to help organizing plenary and concurrent sessions. They are really coming from everywhere on the planet, from New Zealand and Australia, to Hawaii, Galapagos island, Singapore, Tanzania, South Africa, Panama, USA, China, Japan, Israël, UK, The Netherlands, Spain, Germany, and France. In total, many more countries will be represented and we can already list as many as 28 countries represented, scientists from Spain, Germany, USA and France being the most frequent as participants. Montpellier should be the most diverse city in terms of ecologist nationalities, a good point for the year of diversity.

Mongabay: Why was Montpellier chosen as the site for the symposium?

Pierre-Michel Forget: If you think scientific ecology in France, then you necessarily cannot escape the city of Montpellier and its vicinity. And that is the reason why the 1st National Meeting of scientific ecology will also be held in Montpellier between 2-4 September 2010. As is mentioned at FSD2010.org website, the city of Montpellier concentrates one of the largest communities of ecologists, population geneticists and evolutionary biologists in Europe. There are several institutes with expertise on biological control in town. A large part of the research at the partner institutions Centre d’Ecologie Fonctionnelle et Evolutive (CEFE) and the Institut des Sciences et de l’Evolution – Montpellier (ISE-M) focuses on Mediterranean and tropical ecosystems. On the one hand, CEFE focus on important societal concerns: biodiversity, global change and sustainable development, and the overall objective of scientists is to establish scenarios for changes in the structure, functioning and evolution of ecological systems and of strategies for their conservation, restoration and rehabilitation. On the other hand, research at ISE-M focuses on the patterns and mechanisms of evolution in the living world, and aims to better understand the processes involved in the origins and dynamics of biodiversity. Therefore, both CEFE-CNRS and ISE-M at University of Montpellier 2 furnishes a rich scientific environment for the themes of this Symposium-Workshop.

Mongabay: How long has the Frugivore and Seed Dispersal symposium being going on? What is the symposium’s history?

Dr. Pierre-Michel Forget collecting a new species of Carapa at Oku Mount, Cameroon. Photo courtesy of Pierre-Michel Forget. |

Pierre-Michel Forget: In 2010, we will celebrate the Silver Jubilee of the Symposium. It started in 1985 when Ted Fleming and Alejandro Estrada called an international meeting in Mexico of about 50 scientists studying the interactions between frugivores (fruit-eaters) and the seeds they disperse. The 2nd and 3rd FSD, in Mexico (1991) and Brazil (2000), respectively, demonstrated the growth in research on this important topic. The 4th FSD was held in July 2005 at the Nathan campus of Griffith University, Brisbane, Australia, and it provided an important opportunity for academics and managers west of the Pacific (e.g. Australia, southeast Asia) to meet with leaders in the field and new researchers from around the world, and also to demonstrate progress within this region. During the last day of FSD2005, a vote of participants decided that FSD2010 will be held in Montpellier France, to celebrate 25 years (1985-2010) of FSD, and I accepted to chair it, invited a number of participants to help me as Academic committee, and later, invited other colleagues in France to compose the Organizing Committee.

Mongabay: Where would you like to see the symposium and the science of seed dispersal go in the future?

Pierre-Michel Forget: All books that were published resulting from the four previous FSD events soon became key references for students and researchers around the world. In 1985, because I was in the field starting my Ph D thesis in French Guiana I could not attend the 1st FSD. Six years later, I was still unable to attend the 2nd FSD due to lack of funding after my post-doc position at STRI ended. I thus 100 % understand how difficult it can be for post-doc fellows to attend such an important scientific event in their early carrier, especially when away from their home, institution or base. Nonetheless, after listing these pluri-annual events, I also realize that as staff at the Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle, I’ve been lucky enough in the last decade to be invited and able to attend two of them, and to interact with colleagues. But many of students and academics cannot though they wished so much to be there too. It would have been far more profitable to many of them, especially young fellows, to meet and discuss with senior people at the meeting, during break, lunch or in the evening, rather than just reading book chapters. After attending many scientific meetings in the two decades, I especially repeatedly observed the deficit of Africans. It’s only when I attended the AETFAT in 2007 that I was able to meet them. Therefore, I wished that FSD would go to this continent, and it will happen in 2015 as colleagues in South Africa accepted to organize it. Still, it won’t be easy for many South-American and Asian colleagues to attend. Then, we must continue and go to countries where the science of seed dispersal is most needed, where the biodiversity is highly endangered, as in India. Scientists in countries with high income always have opportunities to meet yearly, but not our colleagues from the tropics. Surely, this has a cost in airplane travel and carbon use, but that is the cost to pay to see the conservation of nature and our knowledge passing from one generation to the next. As for the Olympic Games, the stick is passing from one hand to another. Although now needed, virtual meetings will never replace the experience of a human-rich meeting.

Additional articles regarding Pierre-Michel Forget’s work:

New tree species discovered in Guyana is rich source of oil

Proposed gold mine proves controversial in French Guiana rainforest

France blocks controversial rainforest gold mine in French Guiana

Are Brazil nuts really sustainable? Only if hunting is controlled

Related articles

Hunting across Southeast Asia weakens forests’ survival, An interview with Richard Corlett

(11/08/2009) A large flying fox eats a fruit ingesting its seeds. Flying over the tropical forests it eventually deposits the seeds at the base of another tree far from the first. One of these seeds takes root, sprouts, and in thirty years time a new tree waits for another flying fox to spread its speed. In the Southeast Asian tropics an astounding 80 percent of seeds are spread not by wind, but by animals: birds, bats, rodents, even elephants. But in a region where animals of all shapes and sizes are being wiped out by uncontrolled hunting and poaching—what will the forests of the future look like? This is the question that has long occupied Richard Corlett, professor of biological science at the National University of Singapore.

Vanishing forest elephants are the Congo’s greatest cultivators

(04/09/2009) A new study finds that forest elephants may be responsible for planting more trees in the Congo than any other species or ghenus. Conducting a thorough survey of seed dispersal by forest elephants, Dr. Stephen Blake, formerly of the Wildlife Conservation Society (WCS) and now of the Mac Planck Institute for Ornithology, and his team found that forest elephants consume more than 96 species of plant seeds and can carry the seeds as far as 57 kilometers (35 miles) from their parent tree. Forest elephants are a subspecies of the more-widely known African elephant of the continent’s great savannas, differing in many ways from their savanna-relations, including in their diet.

World’s largest bat threatened with extinction due to legal hunting

(08/25/2009) Under the current legal hunting rate scientists predict that the world’s largest bat, the aptly-named large flying fox or Pteropus vampyrus, faces extinction in six to 81 years. Increasing the urgency to save the large flying fox is the vital role it plays as an ecosystem engineer (a species whose behavior can shape an ecosystem); the species maintains Southeast Asian forests by dispersing a wide variety of seeds over distances farther than most birds and other mammals.

New study: why plants produce different sized seeds

(02/17/2010) The longstanding belief as to why some plants produce big seeds and others small seeds is that in this case bigger-is-better, since large seeds have a better chance of survival. However, Helene Muller-Landau, staff scientist at the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute and head of the HSBC Climate Partnership’s effort to quantify carbon in tropical forests, grew dissatisfied with that explanation. For example, if big seeds were always the ‘right’ evolutionary path than why would any plants evolve small seeds? In a new paper in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, Muller-Landau argues for a more complex explanation involving a trade-off between surviving stressful conditions and taking full advantage when the conditions are just right.

Loss in biodiversity may be killing bees

(01/20/2010) A decline in diverse plants species on which to feed may be causing a similar decline in bee survival, according to a new paper in Biology Letters.

How tree communities respond to distance to edges and canopy openness

(12/06/2009) Tropical forests frequently experience the opening and closing of canopy gaps as part of their natural dynamics. When an edge is created, and the area outside the boundary is a disturbed or unnatural system, forests can be seriously affected even at some distance from the fragmented edge, since sunlight and wind penetrate to a much greater extent. This increases tree mortality and, consequently, canopy openness close to the edge. Thus, canopy openness can be both part of a natural gap-dynamics cycle and the direct manifestation of human edge effects.

What types of primates are most prone to extinction in small forest fragments?

(12/06/2009) According to the most recent IUCN assessment, 48 percent of primates are threatened with extinction. Major threats to primates include habitat loss and fragmentation, hunting, and the wildlife trade. A new paper published in Tropical Conservation Science looked at ones of these threats — fragmentation — in an effort to determine what traits put primates at highest risk of extinction in forest fragments. Traits investigated all related to various aspects of primate biology, including: the amount of habitat needed, reproductive rate, and types of specialization. Surprisingly the authors, Matthew A. Gibbons and Alexander H. Harcourt of the University of California at Davis, found no significant relationship between extinction risk and any of the biological parameters.

Governments, public failing to save world’s species

(11/04/2009) According to the International Union for the Conservation of Nature’s (IUCN) 2008 report, released yesterday, 36 percent of the total species evaluated by the organization are threatened with extinction. If one adds the species classified as Near Threatened, the percentage jumps to 44 percent—nearly half.