Venezuelan President Hugo Chávez has been in power for more than ten years, during which time he has deflected numerous electoral challenges, a recall effort, a coup d’etat and even an oil lock out. A politically adroit statesman, he has demonstrated enormous staying power throughout all these political crises.

Yet, Chávez’s luck may have finally run out: a devastating El Niño-linked drought has recently ravaged Venezuela and the government has been forced to undertake conservation measures for water and electricity. Hardly amused, some are holding Chávez responsible for the energy crunch and the drought could exact a heavy toll on the Venezuelan president in September’s legislative elections.

What is causing Venezuela’s energy crisis?

The Guri Dam in Venezuela. |

There may not be a clear cut answer to this question, and different people provide differing interpretations. Chávez critics say that the government has neglected the power grid and failed to invest in hydrology systems and aqueducts in order to expand power production and satisfy increased consumption.

Three years ago, Chávez nationalized several utility companies in an effort to increase state control over the economy and to reverse the trend towards privatization. However, since 2007 there have been several power outages across Venezuela and critics charge that the state has not planned for the long term.

Pointing the Finger at El Niño

Chávez concedes that Venezuela is in the midst of a genuine power and water crisis, and that delays in maintenance and faulty planning have been partly to blame for the recent crunch. However, he has also pointed the finger at weather changes. “It’s El Niño,” Chávez said, referring to the periodic phenomenon in which warming in the Pacific gives rise to unusual weather patterns.

The government blames El Niño, which has resulted in a lack of rainfall, as the cause of water shortages. These shortages in turn have starved Venezuela’s hydroelectric dams which provide approximately three quarters of the nation’s electricity. Venezuela’s largest dam, Guri, has fallen about 30% below its previous record low.

If Chávez is correct and El Niño is responsible for the energy crisis, then this certainly puts an ironic twist on Venezuelan politics. Why? Consider that the key to Chávez’s political success has been petroleum: after wresting control of the oil industry from the country’s corrupt elite, the President used oil revenue to fund key domestic social programs.

Angel Falls in Venezuela. Photo by: Rhett A. Butler. |

Oil was also a key factor in Chávez’s meteoric rise on the international stage: over the past several years Venezuela has provided discounted oil to many countries in Latin America. In exchange, Chávez has been able to secure valuable geopolitical support for his initiatives seeking to counter U.S. influence in the wider region.

But while Chávez’s political success has been inextricably linked to oil largesse, Venezuelan petroleum has exacted a heavy environmental toll on the planet. As I discuss in my book, No Rain in the Amazon: How South America’s Climate Affects the Entire Planet (to be released in a matter of weeks with Palgrave-Macmillan) El Niño may have been thrown out of kilter by climate change. Indeed, scientists believe that El Niño may be increasing in frequency and intensity as a result of global warming.

Throughout the Pacific Basin but also farther afield, El Niño is normally linked with extreme weather like droughts and floods. While prolonged dry periods may prevail in Southeast Asia, Southern Africa, and northern Australia, wetter-than-normal weather hits much of the United States, and heavy rainfall occurs in Peru and Ecuador.

Further inland in South America, El Niño has brought drought and forest fires. While the recent El Niño has proven enormously dislocating for Venezuela, it’s not the first time that the Andean nation has been hit by such weather phenomena: indeed, during the 1997-98 El Niño the country was struck by drought and the authorities were obliged to ration power.

To be sure, Venezuela isn’t the most culpable country when it comes to global warming: that honor lies with the nations of the Global North which pursued industrialization over the past two centuries or more. On the other hand, Venezuela hasn’t helped matters. The Chávez government and previous Venezuelan administrations going back all the way to the 1920s have exported millions of barrels of oil to the U.S. and Europe. That oil has resulted in more carbon emissions being released into the air which in turn has exacerbated climate change and may have led to an intensification of El Niño conditions.

From Angel Falls to Catatumbo Lightning

Certainly, even without El Niño Venezuela has already born witness to the severe effects of climate change. Head to the provincial state of Mérida, for example, and you won’t find too many remaining Andean glaciers. The recent El Niño however has made things worse — Venezuela is experiencing its worst drought in 40 years.

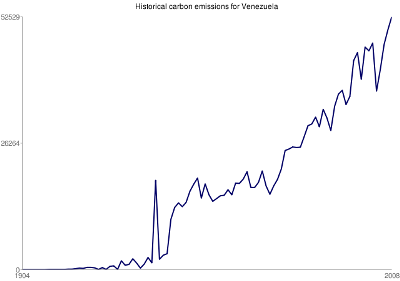

Historical carbon emissions for Venezuela 1904-2008. |

Soursop or guanábana is a delicious fruit but now orchards are drying up for lack of water. In Venezuela’s central plains cereal yields are way down: maize, rice and sorghum have been hit hard. In the Andean highlands meanwhile, coffee production has decreased as the trees flower early and developmental stages of the beans are modified.

Bizarrely, drought and receding waters have uncovered formerly submerged villages. At the Uribante reservoir, local residents were amazed to come across eerie remnants of an old town including a church, demolished houses, a cemetery and a square.

Angel Falls, a popular tourist destination, has shed up to a third of its water volume. The site is named after U.S. pilot Jimmy Angel, who in the 1920s landed on top of the mesa where the waterfall starts. Visitors are normally taken aback at the site’s majestic appearance but now the falls have turned into a small stream.

Another captivating sight is the so-called Catatumbo lightning over Lake Maracaibo in western Venezuela. A unique meteorological phenomenon which lights up the night sky, Catatumbo lightning only occurs in the Catatumbo River Basin near the Colombian border. Recently, however, the lightning disappeared, prompting the Guardian newspaper to write that the phenomenon’s absence “appears to be a casualty of the El Niño weather phenomenon which has caused a severe drought in Venezuela, disrupting the conditions that produce the lightning.”

Even as Maracaibo residents wonder what has befallen their beloved Catatumbo Lightning, across the country in Caracas local residents have also been befuddled. El Ávila, a mountain located near to the capital city, has been subject to numerous fires which have blanketed Caracas in smoke and raised temperatures, particularly at night.

Economic and Social Impact

Venezuela, which has already been hit by recession, can ill afford a natural disaster of this caliber. As a result of El Niño, Chávez has had to cut power use to government departments by 20 percent and most government offices have been operating only half the day. “Turn off the light, buddy,” Chávez remarked. “Don’t leave the TV on. We’re going to create a real saving campaign.”

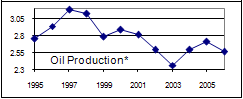

Oil production in Venezuela. |

In some regions, rationing has been in place for up to 14 hours a week. Hoping to set a positive example, Chávez said he would turn down the air conditioner and turn off more lights at the presidential palace. All in all, the electricity crunch may act as a drag on the economy for years to come, dashing Chávez’s hopes for GDP growth, cutting into fuel exports and forshadowing lengthy rationing.

In hospitals, blackouts have interrupted surgeries while power outages shut down street lights as well as the Caracas subway system. In the Venezuelan capital, residents suffering from the heat wave have switched off their air conditioners to save electricity and avoid being punished by the government, which has said it would fine or even cut off consumers who waste power. Housewives wash dishes by hand instead of turning on the dishwasher. People work out at the gym without any AC.

Meanwhile, state-owned oil, aluminum and steel company are obliged to “rationalize” their electric use. Steel company Sidor, a large manufacturer, has been running at less than 50 percent capacity. Oil is a particular concern: Venezuela is the Western Hemisphere’s top crude exporter and though petroleum fields are mostly protected by their own generation plants, power shortages could affect exploration and field maintenance. That in turn could mean that oil would be more costly to pump.

In Caracas, the city’s main water utility announced it would reduce water supply by 25 percent per person. Speaking to his fellow citizens, Chávez urged the public to limit its showers to three minutes. “Some people sing in the shower, in the shower half an hour,” he said. “No kids, three minutes is more than enough. I’ve counted, three minutes, and I don’t stink.”

El Niño Political Football

In Venezuela’s highly charged political environment, even the weather and energy crunch have come to be politicized. Indeed, Chávez has blamed Venezuela’s troubles on the wealthy, who own swimming pools, compulsively wash their cars and have TV sets in every room.

Hugo Chavez with Russian President, Vladimir Putin at the Kremlin in Moscow. Photo courtesy of www.kremlin.ru. |

“Those who waste the most are the rich,” Chávez declared. “If you are going to lie back, in the bath, with the soap and you turn on the what’s it called, the Jacuzzi … imagine that, what kind of communism is that?” the Venezuelan leader added amusingly. “We’re not in times of Jacuzzi.”

Perhaps not surprisingly, Chávez has singled out shopping malls, warning the businesses that they waste too much power. “They’re going to have to buy their generator, and if not I’ll cut off their power,” Chávez said. True to form, the wealthy have bristled. “In a certain way, Chávez is attacking capitalism with the orders on shopping malls,” exclaimed Emilio Grateron, mayor of Caracas’ Chacao municipality, a hotbed of the political right. “By limiting the hours we can go to malls, he is trying to slowly take away liberties, to create absolute control over things such as shopping.”

Though analysts say shopping malls use less than 1% of the power in Venezuela, they have become a major focus of the government. Indeed, the authorities told most stores that they could only be open between 11 a.m and 9 p.m. However, the 9 p.m. closing time proved too drastic for cinemas, which all of a sudden had to begin screening their last films at 7 p.m. As a result, the government made some exceptions for movie theaters and some bars and restaurants.

Needless to say, thousands have taken to the streets to protest the water and electricity crunch. Some have burned electricity bills while others brandish surge-damaged blenders, televisions and stereos outside the state utility company. What’s more, the energy crunch has now had a serious political spillover effect: in a daring move, former Chávez aides such as Defense Minister Raul Isaias Baduel have signed a petition asking for the President to resign.

The statement said that after 11 years in power, it was important for Chávez to resign so as to protect the country from a continuation of various “ills.” Lashing back at his critics, Chávez declared “The squalid ones [the President’s usual term for the opposition] are hoping it won’t rain.” “But it’s going to rain, you’ll see,” Chávez added, “because God is a ‘Bolivarian’ [Chávez’s term for his own political movement, which he models after independence leader Simon Bolívar]. God cannot be squalid. Nature is with us.”

Structural Limitations

With legislative elections approaching in September, Chávez is hoping that El Niño won’t spell political trouble. Fanning out around Caracas, soldiers have been distributing energy-saving light bulbs imported from China and the authorities have set up diesel-powered generators in affected regions. What’s more, Chávez will ban the import of products that use excessive electricity, and will in addition increase electricity charges on heavy users. In response to the crisis, the President also fired his electricity minister and called in foreign experts.

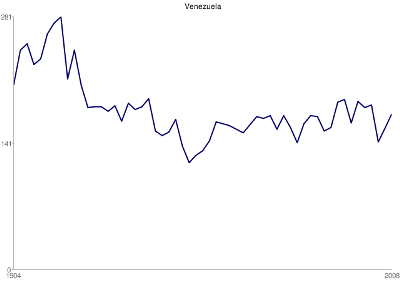

Venezuela’s carbon emissions per capita 1904-2008. |

Chávez also seeks to speed up construction of new power plants. In light of the country’s energy defiencies, that’s become a political imperative: Venezuela has a total demand of 17,300 megawatt-hours and that rate is increasing at a yearly six or seven percent. Therefore, Chávez needs 24,000 megawatt-hour capacity to cope with breakdowns or emergencies.

At this point, however, Venezuela has a poorly maintained power distribution network and only has a generating capacity of 16,400 megawatt-hours. Chávez has plans to buy new power turbines which would run on natural gas or diesel, but they will cost at least $4 billion.

The buying spree would be one of the biggest and most hurried the world has ever witnessed and would require Venezuela to shelve out huge premiums for turbines that usually take a year or more to be delivered. “Anyone who walks in the door with a power plant, they’re gonna buy it,” said one financial expert. “They are in panic mode.”

Another additional difficulty has to do with powering the new plants. Venezuela is not expecting new gas supplies this year, so the plants would have to run on diesel fuel. This will reduce the plants efficiency by up to a third and burning diesel at the new plants could force Venezuela to slash fuel shipments and import diesel.

Chávez’s “Katrina” Moment?

On the plus side, Venezuela’s next rainy season is due in a little over a month. Relief would come no time too soon: authorities warn that the Guri reservoir could reach dangerously low levels as early as May or June if more rain doesn’t fall. Hopefully Venezuela will receive precipitation, but again meteorologists caution that there could be delays this year as a result of El Niño.

The energy emergency has forced Chávez to improvise. U.S. ally Colombia, Chávez’s nemesis, is reportedly going to sell electricity to Venezuela. Meanwhile, in something out of a bizarre Hollywood sci-fi picture, Chávez says he will “bombard” clouds in an effort to produce rain and alleviate drought. With help from Cuban experts and specialized equipment, Venezuela hopes to seed clouds from planes.

So-called cloud seeding has been attempted in various countries, usually by releasing silver iodide particles into clouds. Though efforts to modify the weather have proved controversial and critics have questioned the technique’s effectiveness, Chávez is optimistic. “Any cloud that comes in my way, I’ll hurl a lightning bolt at it,” the Venezuelan remarked. “Tonight I’m going out to bombard.”

Like former U.S. President Bush, who was politically undone by a hurricane, Chávez may be currently facing his own “Katrina-like” moment. “Whether there will be another decade of Chávez could depend on rain,” remarks the Guardian’s Rory Carroll.

Nikolas Kozloff is the author of No Rain in the Amazon: How South America’s Climate Change Affects the Entire Planet (to be released in a matter of weeks with Palgrave-Macmillan) and Revolution! South America and the Rise of the New Left (Palgrave, 2008). Visit his blog at www.nikolaskozloff.com.

Related articles

Copenhagen Climate Summit: Hugo Chávez is an Inappropriate Environmental Messenger

(12/17/2009) Like him or not, one thing is for sure: the flamboyant Hugo Chávez has never shied away from the limelight. I was therefore somewhat surprised to read some initial press accounts suggesting that the Venezuelan leader might stay away from the United Nations climate summit being held in Copenhagen, Denmark. “If it’s to go and waste time, it’s better I don’t go,” he said. “If everything is already cooked up by the big [nations], then forget it.” Chávez however hinted that he might change his mind if ALBA nations could reach some type of common position towards the Copenhagen summit. ALBA, an initiative designed to facilitate trade and reciprocity amongst like minded progressive regimes in Latin America, has taken up the issue of climate justice as of late. Two months ago Bolivian President and ALBA ally Evo Morales called for the creation of an actual climate justice tribunal. The Global North, Morales said, should indemnify poor nations for the ravages of climate change.

High gold prices, army collaboration, play role in mining invasion in southern Venezuela

(11/25/2009) Illegal gold mining involving wildcat miners, the Venezuelan army, and indigenous groups is threatening one of the country’s most biodiverse river basins, according to local sources.

Venezuela plans 5000-mile pipeline across Amazon rain forest

(01/25/2006) Hugo Chavez, Venezuela’s president, announced a plan to build a massive gas pipeline that would carry natural gas from the oil rich state 5,000 miles south. Environmentalists fear that the project could damage the Amazon rain forest by polluting waterways and creating roads that would attract developers and poor farmers, while analysts question the wisdom and viability of the plan which may cost $20-50 billion depending on who makes the estimate.