The Gulf of California’s once rich marine ecosystem is in trouble. Surveys from 1999 and 2009 revealed that during the ten-year-period 60 percent of the areas showed signs of degradation, including the loss of top predators necessary to keep an ecosystem healthy, for example sharks, groupers, and snappers.

“In these studies, whether reefs or mangroves, we are trying to show that the destruction on the coast and overexploitation in other areas are diminishing the biomass (the amount of organisms in an ecosystem) in several areas,” said Octavio Aburto-Oropeza with the Scripps Institution of Oceanography at UC San Diego, who participated in both surveys. “With lower biomass, the large predators, the keys to a robust marine ecosystem, are missing and that causes disruption down the marine food web.”

More intensive fishing methods are driving the decline, according to Aburto-Oropeza. Fishermen have left behind the traditional hook and line for ecologically-destructive gillnets and ‘hookah’ fishing, where fishermen concoct oxygen piping to walk along the seafloor, killing fish and marine invertebrate in massive numbers at night while they sleep.

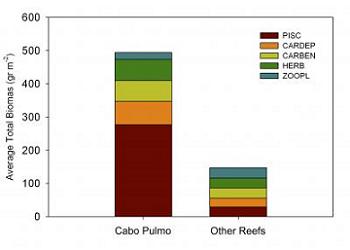

Top: More than 20 different groups of high-value commercial species, including invertebrates such as blue crabs and fish such as snappers, grunts and snooks, are part of the mangrove forests of the Gulf of California, including this forest off Dazante Island inside the Loreto marine protected area. Bottom: The average fish biomass from a 2009 expedition reveals that Cabo Pulmo has recovered its marine community. Piscivores (red, fish feeders) dominate, followed by active carnivores (orange) and benthic carnivores (yellow). Their prey, herbivores (green) and zooplanktivores (blue), follow. Other reefs feature less fish biomass on average and a homogenization of the relative biomass of these groups. Photo and Graph courtesy of: Scripps Institution of Oceanography, UC San Diego. |

Despite drastic ecological declines—in some areas researchers have found that blue-green algae has completely replaced once-diverse reef systems—Aburto-Oropeza argues that better protection and increasing marine reserves could undo the damage.

As an example, he points to Cabo Pulmo, a protected area near the southern tip of the Baja peninsula, which has restricted fishing since 1995. There a healthy and diverse community of marine life thrives.

“Different sites recover in different ways, but they all have increased in biomass, especially top predators,” explains Aburto-Oropeza. “The common thing is that they have reduced or eliminated fishing activity.”

In addition he points to the importance of protecting ‘strategic’ sites, such as fish spawning aggregating areas, where fish gather enmasse to reproduce.

“For some species these spawning aggregation events occur two to four times per year, and can represent 100 percent of the replenishment of their populations,” explains Aburto-Oropeza.

Mangroves, which provide an essential habitat for fish nurseries, are also vital for conservation efforts. Aburto-Oropeza and other researchers recently calculated the economic value of mangroves at $37,500 US dollars per hectare per year. Yet mangroves remain one of the most threatened habitats on Earth.

Related articles

UN to protect seven migratory sharks, but Australia opts out

(02/17/2010) One hundred and thirteen countries have signed on to an agreement to protect seven migratory sharks currently threatened with extinction byway of the Convention on the Conservation of Migratory Species of Wild Animals (CMS), according to the UN Environment Program (UNEP). The agreement prohibits hunting, fishing, or deliberate killing of the great white shark, basking shark, whale shark, porbeagle shark, spiny dogfish, as well as the shortfin and longfin mako sharks. However, Australia has declared it will ignore certain protections.

Expedition to save world’s rarest cetacean threatened by lack of funding

(02/11/2010) Little known beyond the waters of the Gulf of California, the world’s smallest cetacean (a group including whales, dolphins, and porpoises) is hanging on by a thread. The vaquita—which in Spanish means ‘little cow’—has recently gained the dubious distinction of not only being the world’s smallest cetacean, but the also the world’s rarest. In 2006 it was announced that the Yangtze river dolphin, or baiji, was likely extinct, and conservationists fear the Critically Endangered ‘little cow’ is next. An expedition for this year is set to identify vaquita individuals, but even this is threatened by lack of funding.

86 percent of dolphins and whales threatened by fishing nets

(02/07/2010) A new report from the United Nations Environment Program (UNEP) finds that almost 9 out of 10 toothed whales—including dolphins and porpoises—are threatened by entanglement and subsequent drowning from large-scale fishing operations equipment, such as gillnets, traps, longlines, and trawls. These operations threaten the highest percentage (86 percent) of the world’s toothed whales.