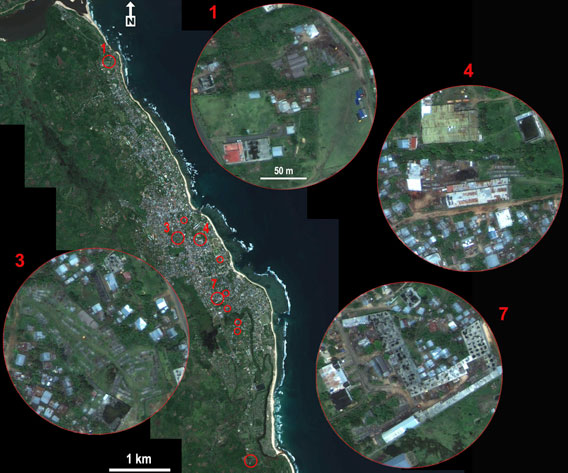

Analysts in Europe and the United States are using high resolution satellite imagery to identify and track shipments of timber illegally logged from rainforest parks in Madagascar. The images could be used to help prosecute traders involved in trafficking and put pressure on companies using rosewood sourced from Madagascar.

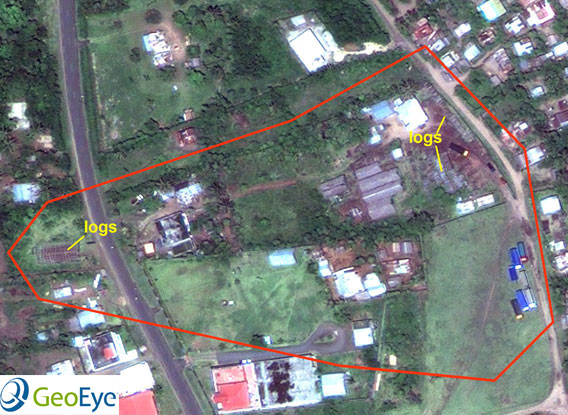

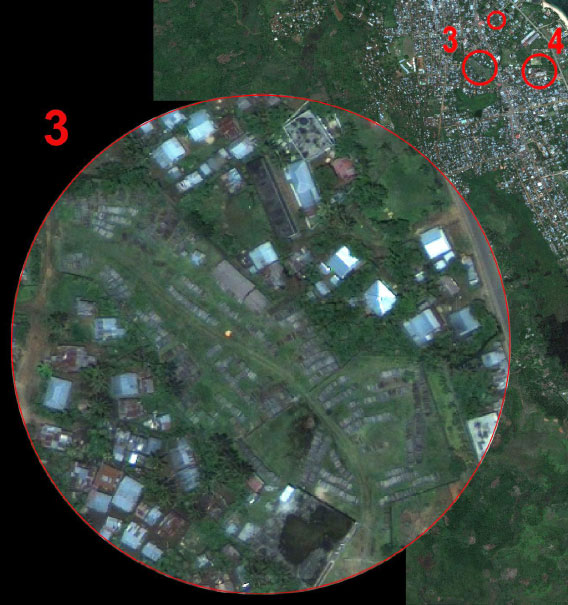

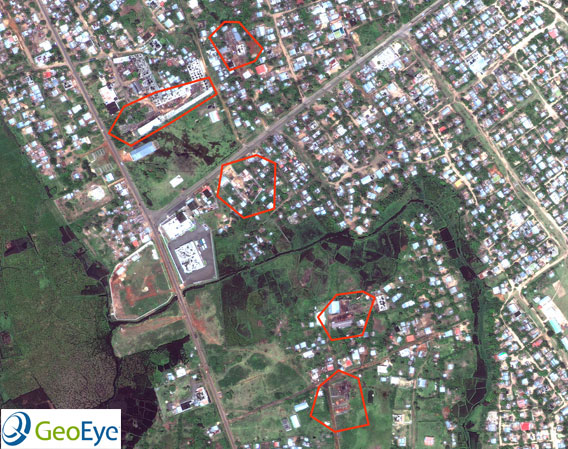

Illegal logging of precious hardwoods in Madagascar’s national parks exploded in the aftermath of a military coup last March. The coup — which displaced the increasingly autocratic, but democratically elected president, Marc Ravalomanana — triggered a collapse in governance, which was exacerbated when donor countries pulled financial aid. Without funding, and under pressure from criminal syndicates operating primarily in the northeastern part of the country, park rangers abandoned their posts and loggers moved in, harvesting hundreds of millions of dollars worth of rosewood and ebony from tens of thousands of hectares of protected areas. Typically the logs were transported from forest areas to ports, where they were loaded onto ships. Much of the cargo was carried by foreign freighters to Reunion and Mauritius before going on to China. But since the harvesting and trafficking of rosewood was illegal, a large portion of the logs were hidden in stockyards and buried on beaches.

The Missouri Botanical Garden has taken a leadership role in working to address the logging crisis in Madagascar. |

Last month “transitional authority” leader Andry Rajoelina authorized rosewood export, ushering in a new frenzy of activity. Eyewitnesses have reported the presence of “more than 1,000” loggers in Masoala National Park and Makira Natural Park, reserves renowned for their biodiversity, and “long queues of trucks” carrying rosewood to Vohemar, a major port in the region. There are indications that hundreds of containers of rosewood will soon be moved from Vohemar to Tamatave, the country’s largest port, for export. Rosewood stockpiles are being uncovered, dug up and readied for shipment.

|

But while traders may be able to evade detection locally by concealing their contraband or through bribery, timber stocks and timber-carrying trucks and boats are clearly visible to the rest of world via regularly-updated, high resolution satellite imagery. Organizations and international law enforcement agencies are therefore capable of monitoring storage and movement of the illegally sourced timber. Furthermore, new techniques make it possible to determine the origin of wood through its chemical composition, giving authorities powerful investigative capabilities when working to enforce trade laws like the Lacey Act in the United States and FLEGT in Europe. These regulations put the burden of responsibility on importing companies, holding them to the environmental laws of producing countries, even when those countries are unwilling or unable to enforce their rules.

Peter Raven, Pete Lowry, and others at the Missouri Botanical Garden have been working with Clinton Jenkins of the University of Maryland to prepare and analyze images from the GeoEye-1 satellite. The Missouri Botanical Garden is one of the only large NGOs working to address the logging crisis in Madagascar. |

In the case of Madagascar rosewood, there has already been enforcement action under the Lacey Act: in November, U.S. federal agents raided Gibson Guitar’s factory in Tennessee due to concerns that the company had been using illegally harvested rosewood from Madagascar. At least one major Malagasy trader, Jeannot Ranjanoro, could be directly at risk since he does business under Flavour Handling LLC, a corporation based in Delaware. As a U.S. company, if Flavour Handling is shown to be involved in timber trafficking that violates Madagascar’s environmental laws, it could be potentially exposed to prosecution under the Lacey Act. Satellite imagery and chemical signatures of wood could serve as the evidence.

|

Related articles

Coup leaders sell out Madagascar’s forests, people

(01/27/2010) Madagascar is renowned for its biological richness. Located off the eastern coast of southern Africa and slightly larger than California, the island has an eclectic collection of plants and animals, more than 80 percent of which are found nowhere else in the world. But Madagascar’s biological bounty has been under siege for nearly a year in the aftermath of a political crisis which saw its president chased into exile at gunpoint; a collapse in its civil service, including its park management system; and evaporation of donor funds which provide half the government’s annual budget. In the absence of governance, organized gangs ransacked the island’s biological treasures, including precious hardwoods and endangered lemurs from protected rainforests, and frightened away tourists, who provide a critical economic incentive for conservation. Now, as the coup leaders take an increasingly active role in the plunder as a means to finance an upcoming election they hope will legitimize their power grab, the question becomes whether Madagascar’s once highly regarded conservation system can be restored and maintained.