Balikpapan Bay in East Kalimantan is home to an incredible variety of ecosystems: in the shallow bay waters endangered dugong feed on sea grasses and salt water crocodiles sleep; along the bay proboscis monkeys leap among mangroves thirty meters tall and Irrawaddy dolphins roam; beyond the mangroves lies the Sungai Wain Protection forest; here, the Sunda clouded leopard hunts, sun bears climb into the canopy searching for fruits and nuts, and a reintroduced population of orangutans makes their nests; but this wilderness, along with all of its myriad inhabitants, is threatened by a plan to build a bridge and road connecting the towns of Penajam and Balikpapan.

The bridge, known as Pulau Balang, would span the bay, splicing through Balang Island, cutting off the mangroves from the rainforest, and running the entire length of the western edge of the protected forest. While the direct impacts would be severe—deforestation for the road, splitting the mangrove from the rainforest, damage to the reef—researchers say that providing people easy access to the mangrove and forests will inevitably destroy them.

“The most serious threats are the indirect ones, notably opening an uncontrollable access to the whole area,” Stanislav Lhota, a primatologist with the University of South Bohemia, told mongabay.com.

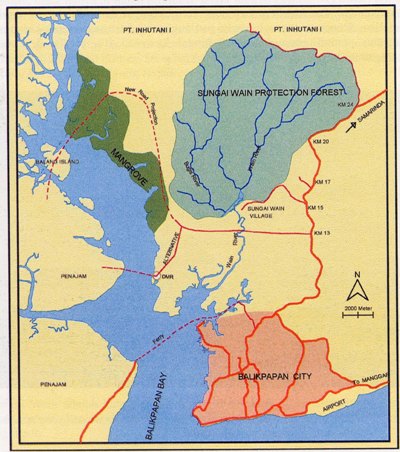

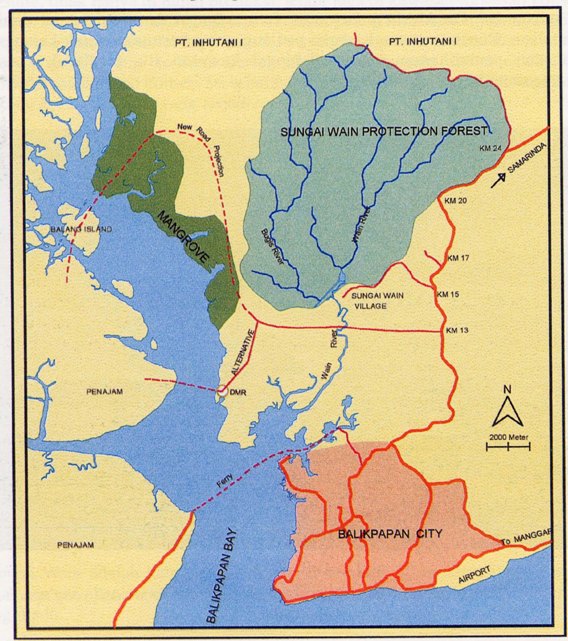

Map showing proposed road and bridge and shorter alternative (larger image at the end of the article). Image courtesy of Stanislav Lhota. |

The project “will open access for settlements, farming, illegal logging, more land speculation, subsequent forest fires, poaching of wildlife, illegal logging. In effect it will cause the destruction of the mangrove area and all wildlife there, but also (slow but certain) destruction of the western side of the Sungai Wain forest,” Dr. Gabriella Fredriksson says. Fredriksson, an expert on sun bears, has worked on managing and conserving the Sungai Wain Protection Forest for over a decade.

“The destruction of the mangroves will also impact the fragile marine wildlife in the [Balikpapan] bay and fisheries due to destruction of fish breeding areas,” adds Dr. Danielle Kreb of the local NGO RASI, who has studied the marine mammals in Balikpapan Bay for several years and noticed that the Irrawaddy dolphins’ core habitat is in the vicinity of Pulau Balang.

Despite the clear environmental impact outlined by conservationists, the provincial and federal governments support the project. Local governments, however, have signalled over the past couple months that they oppose the project, especially since there is an alternative plan that would threaten none of the ecosystems, and in addition provide a far shorter route between Penajam to Balikpapan.

A lost wilderness?

Sungai Wain protected forest. Photo by: Marian Bartos. |

If the Pulau Bridge project goes ahead, Balikpapan Bay will be forever changed. The already shallow bay will face erosion and sedimentation from construction work on the surrounding hills, making the bay less accessible for large boats and leading to more frequent flooding of the coastal villages. Species in the bay, such as dugongs, crocodiles, and green sea turtles—already affected by sedimentation—would likely face further impacts from pollution.

The mangroves—an ecosystem that has faced heavy losses worldwide—would be severely impacted as well. The green corridors allowing species to move between the mangrove ecosystem and the Sungai Wain protection forest will be altogether broken.

“Fauna such as proboscis monkeys and many other species cannot survive in long term in mangroves alone,” Lhota explains. “They need regular access to the neighboring forest where they find numerous key resources. Mangroves alone are rather inhospitable environment with only limited food sources. If they are isolated from other forests, they may apparently survive but they will gradually turn into a lifeless stand of Rhizophora trees.”

The eventual loss of the mangroves also threatens the local fishing trade since fish require the mangrove forest for breeding: the mangrove stand in question is the last place for fish in the bay to breed.

“East Kalimantan only has a small mangrove area left, because much of the mangrove area [has] already [been] converted to shrimp ponds and industry. And on Balikpapan, [this] is [the] last mangrove forest,” says Ade Fadli of BEBSiC, a local conservation group.

The road connecting the bridge to Balikpapan would next pass along the western edge of the Sungai Wain forest reserve, the last major stand of dipterocarp trees along the south and central coast. While the direct impact of road building to the forest reserve would likely be minimal, the road would open the reserve to “illegal logging, land clearance, and above all, forest fires,” according to Lhota.

A male proboscis monkey. It is estimated that 5 percent of the world’s proboscis monkeys are in the mangroves around Balikpapan bay. Photo by: Petr Colas. |

Fire is the most significant threat to the forest. While tropical forests rarely burn under natural conditions, human impacts in Indonesia has left a scar of burning across Kalimantan. Sungai Wain contains the last unburnt primary forest in the area; in 1998 devastating fires spilled across the region, but only burnt a part of Sungai Wain.

“The [Sungai Wain] forest, which was burned only once, regenerates well but becomes highly prone to subsequent fires due to the decrease in humidity and huge quantities of highly flammable dead wood,” Lhota explains. “If it burns a second time, it can no longer regenerate easily. With the current tendency of governments to consider such forest as ‘lost forever’, it is likely to be doomed to further encroachment and conversion.”

Home to over 100 mammal species and over 250 bird species, the loss of the forest would devastate tropical species, including a population of reintroduced orangutans.

In addition, the forest is as a catchment source of clean water for the state-owned oil company Pertamina, and the Kariangau Baru industrial area. The loss of the forest would endanger the water needs of these industries, which uses it for cooling in refineries and drinking for employees.

The Sungai Wain forest “is the last watershed covered with forest and hence supplying freshwater on an ongoing basis. The water from this reserve has been used for the oil industry and its workers/households (which make up almost 20 percent of the population in Balikpapan) since 1945,” Fredriksson explains.

According to Lhota, Balikpapan Bay has huge ecotourism and education potential which has largely gone untapped.

Not much left

Mangroves of Balikpapan bay. Photo by: Petr Slavik. |

Road-building causing forest destruction is hardly a new problem: already Kalimantan has several examples in the region. Roads have destroyed the Kutai National Park, the Bukit Soehato Conservation Forest, and the Manggar Protection Forest. These wildernesses have lost nearly all of their primary forest, and most of the parks have been entirely burnt at least once.

The process of slow destruction by human impacts has already begun in Sungai Wain forest, which is threatened by a road being constructed along its southern side.

“There is a lot of illegal logging going on freely along the road, land is being opened fast by felling and burning and first small houses started to appear on the both sides of the road. This is an uncontrollable process,” says Lhota. Despite government promises of better monitoring, increased law enforcement, and protections of the forest, “in practice, no protected area along a provincial road in East Kalimantan was able to survive.”

A number of species in the area are threatened with extinction worldwide. The bay cat, flat-headed cat, Bornean orangutan, storm’s stork, Bornean gibbon, proboscis monkey, and Bornean peacock pheasant are all listed as Endangered by the IUCN Red List.

The forest is also home to the white-fronted langur, an elusive primate who was only photographed for the first time in 2005. Most of the existing photographs are from the Sungai Wain forest.

White-fronted lanngur in the Sungai Wain forest. Photo by: Milan Janda. |

For Fredriksson, who studies the sun bear, classified as Vulnerable, the project would severely impact the local population she has spent years studying.

“It will isolate even further an already fragile and small population of sun bears, ironically the mascot of the [Balikpapan] district since 2004. It will destroy the home-ranges of several bears, it will further increase poaching of bears (through snares) […]” Fredriksson says. “I would estimate that the population of sun bears will be halved due to this road and will make the population highly prone to much quicker extinction.”

Alternative route

This doesn’t have to happen. According to conservationists, a simple alternative route exists that would preserve the bay, mangroves, and forest. The alternative would also be a quicker route for the local people to drive between Balikpapan and Penajam. Under the current plan one will have to drive an additional 80 kilometers between Penajam and Balikpapan, which would take longer than simply taking the already-available ferry service. The alternative projects calls for bridge and road to be built at the very southern edge of the bay, completely bypassing the mangroves and the rainforest. Perhaps most important for the politicians, while the alternative plan would cost more upfront, it will prove cheaper in the long run.

Sungai Wain forest. Photo by: Marian Bartos. |

“No one has yet attempted to calculate the enormous economical loss due to the environmental damage caused by the Pulau Balang variant and the huge investments which would have to be paid indefinitely by both local governments to fight the resulting environmental disaster,” says Lhota.

In addition to environmental costs, the project ignores higher maintenance costs since the road will be built on land-slide prone hills and will be considerably longer than the alternative. The economic cost of local industries losing dependable water source has also not been calculated. While the alternative route is more expensive upfront, in the long-term it will likely prove considerably cheaper compared to the Pulau Balang bridge

A second alternative would be to skip new road building altogether and simply improve the ferry transport between Balikpapan and Penajam while enhancing existing roads.

While the Pulau Balang Bridge project has undergone an Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA), Lhota says the EIA is hardly satisfactory.

“My assistants and I spent one month in the area by voluntarily collecting data to be included in EIA but nothing of it was used. Given the nature of the data, the EIA document overlooks many of the principal threats to the area, such as the threat of fires to the Sungai Wain Protection Forest, the threat of extinction of mangrove fauna due to its isolation from the other forests and many others. […] Furthermore, the EIA document is hardly available (it took me four years to get a copy of it and almost no other conservationists have ever accessed it) and it is practically never consulted […] It is clear that the only purpose for conducting EIA study was to fulfil the legal requirement of having an EIA document and not to evaluate the environmental impact assessment of the project.”

Going forward: local versus provincial and federal

The Bornean gibbon is listed as Endangered by the IUCN Red List. Photo by: Petr Colas. |

Recently, local governments, perceiving the many negative aspects of the project, have stepped away from supporting the Pulau Balang Bridge. Instead they have put their support behind the alternative road that would cause far less environmental harm and be a better option for their communities.

As Ade Fadli explains: “local people only want to get [the] best transportation facilities.”

Yet the provincial and federal governments remain staunch supporters, capable of pushing the Pulau Balang Bridge through despite local concerns. Already, funds for the bridge and road have been secured by investors from South Korea.

“The provincial government simply ignores the environmental issues. They claim that there is a need to improve transportation between East and South Kalimantan, which is right, but it does not explain why to select the Pulau Balang Bridge variant of the provincial road in favor of any of the several suggested alternatives,” Fredriksson says.

Behind some of the government’s support could be corruption: many individuals strand to gain hefty government payouts for land speculation.

Sunset over the mangroves. Photo by: Stanislav Lhota. |

“The main reason I can see for wanting to build this specific road route is that it is the longest road (i.e. the biggest project expense) and the largest area available for land speculation, which has been ongoing since the early 1990s when the road was first planned/started to being built. A large number of influential people at both province and local government level have bought land and will see large profits when this road will gets built,” Fredriksson says.

“I currently do not know who all bought the land along the proposed provincial road but these people are probably very influential, and, of course, highly motivated stakeholders. Corruption is an integral part of Indonesian culture and local rumors explain some of the government’s decisions in this light,” an anonymous source said, adding that, “of course, these rumors cannot be proved.”

In the end the building of the road would be another loss in a long list of losses for Indonesian biodiversity and forests. The island nation—which has one of the largest deforestation rates in the world, losing nearly 25 percent of its forest in 15 years—is the third largest emitter of greenhouse gases after China and the United States almost entirely due to carbon emissions related to deforestation. In addition, the island of Borneo has lost nearly 50 percent of its forest cover since the 1970s, despite increasing understanding of the importance of rainforests for ecological services like carbon sequestration, biodiversity preservation, and freshwater catchments.

Despite Indonesia’s disturbing history, conservationists hope that this time the provincial and federal governments will come around and see that ensuring the preservation of the forest reserve—not to mention the mangroves and the bay itself—is the best way forward both environmentally and economically.

A few notable species in the area:

Mammals:

Male proboscis monkey. Photo by: Petr Colas. |

Endangered:

Bay cat (Pardofelis badia)

Bornean orangutan (Pongo pygmaeus)

Bornean gibbon (Hylobates muelleri)

Flat-headed cat (Prionailurus planiceps)

Proboscis monkey (Nasalis larvatus)

Vulnerable:

Bornean slow loris (Nycticebus menagensis)

Dugong ( Dugong dugon)

Irrawaddy Dolphin ( Orcaella brevirostris)

Marbled cat (Pardofelis marmorata)

Pig-tailed macaque (Macaca nemestrina)

Sun Bear (Helarctos malayanus)

Sunda clouded leopard (Neofelis diardi)

Western tarsius (Tarsius bancanus)

White-fronted langur (Presbytis frontata)

Least Concern:

Maroon langur (Presbytis rubicunda)

Leopard cat (Prionailurus benhalensis)

Long-tailed macaque (Macaca fascicularis)

Silvered langur (Trachypithecus cristatus)

Birds:

The Dugong is listed as Vulnerable by the IUCN Red List. Photo by: Julien Willem. |

Endangered:

Bornean Peacock Pheasant (Polyplectron schleiermacheri )

Storm’s Stork (Ciconia stormi)

Vulnerable:

Blue-headed Pitta (pitta baudii)

Bornean Wren-babbler (Ptilocichla leucogrammica)

Near Threatened:

Bornean Bristlehead ( Pityriasis gymnocephala)

Bornean Ground Cukoo ( Carpococcyx radiceus)

Reptiles/Amphibians:

Endangered:

False gavials, reports of a few surviving individuals (Tomistoma schlegelii)

Green sea turtles (Chelonia mydas)

Least Concern:

Saltwater Crocodile ( Crocodylus porosus)

Map of provincial road and bridge, as well as alternative. Image courtesy of Stanislav Lhota.

Related articles

Video: rare footage of the sun bear, the world’s smallest, making a nest in the canopy

(12/06/2009) Sun bear expert, Siew Te Wong, has captured rare footage of the world’s smallest bear making a nest high in the canopy. The sun bear in the video is a radio-collared individual that Wong is keeping tabs on in Borneo.

Indonesia: Kalimantan’s Lowland Peat Forests Explained

(12/04/2009) Earth’s tropical rainforests are a critical

component of the world’s carbon cycle yet cover only about 12% of its

terrestrial land. Accounting for 40% of the world’s terrestrial carbon and 50%

of the world’s gross primary productivity,[1].

the production of organic compounds primarily through photosynthesis, tropical

rainforests also are one of the engines driving Earth’s atmospheric circulation

patterns.

40% of lowland forests in Sumatra and Indonesian Borneo cleared in 15 years

(11/10/2009) Forty percent of lowland forests in Sumatra and Kalimantan (Indonesian Borneo) were cleared from 1990 to 2005, reports a new high resolution assessment of land cover change in Indonesia.

World’s first video of the elusive and endangered bay cat

(11/05/2009) Rare, elusive, and endangered by habitat loss, the bay cat is one of the world’s least studied wild cats. Several specimens of the cat were collected in the 19th and 20th Century, but a living cat wasn’t even photographed until 1998. Now, researchers in Sabah, Malaysian Borneo, have managed to capture the first film of the bay cat (Catopuma badia). Lasting seven seconds, the video shows the distinctly reddish-brown cat in its habitat.

Photos: Palm oil threatens Borneo’s rarest cats

(11/04/2009) Oil palm expansion is threatening Borneo’s rarest wild cats, reports a new study based on three years of fieldwork and more than 17,000 camera trap nights. Studying cats in five locations—each with different environments—in Sabah, Malaysian Borneo, researchers found that four of five cat species are threatened by habitat loss due to palm oil plantations. “No other place has a higher percentage of threatened wild cats!” Jim Sanderson, an expert on the world’s small cats, told Mongabay.com. Pointing out that 80 percent of Borneo’s cats face extinction, Sanderson said that “not one of these wild cats poses a direct threat to humans.”

Roads are enablers of rainforest destruction

(09/24/2009) Chainsaws, bulldozers, and fires are tools of rainforest destruction, but roads are enablers. Roads link resources to markets, enabling loggers, farmers, ranchers, miners, and land speculators to convert remote forests into economic opportunities. But the ecological cost is high: 95 percent of deforestation in the Brazilian Amazon occurs within 50-kilometers of a road; in Africa, where logging roads are rapidly expanding across the Congo basin, the bulk of bushmeat hunting occurs near roads. In Laos and Sumatra, roads are opening last remnants of intact forests to logging, poaching, and plantation development. But roads also cause subtler impacts, fragmenting habitats, altering microclimates, creating highways for invasive species, blocking movement of wildlife, and claiming animals as roadkill. A new paper, published in Trends in Evolution and Ecology, reviews these and other impacts of roads on rainforests. Its conclusions don’t bode well for the future of forests.

Oil road transforms indigenous nomadic hunters into commercial poachers in the Ecuadorian Amazon

(09/13/2009) The documentary Crude opened this weekend in New York, while the film shows the direct impact of the oil industry on indigenous groups a new study proves that the presence of oil companies can have subtler, but still major impacts, on indigenous groups and the ecosystems in which they live. In Ecuador’s Yasuni National Park—comprising 982,000 hectares of what the researchers call “one of the most species diverse forests in the world”—the presence of an oil company has disrupted the lives of the Waorani and the Kichwa peoples, and the rich abundance of wildlife living within the forest.

Rehabilitation not enough to solve orangutan crisis in Indonesia

(08/20/2009) A baby orangutan ambles across the grass at the Borneo Orangutan Survival Foundation’s Nyaru Menteng rehabilitation center in Central Kalimantan, in the heart of Indonesian Borneo. The ape pauses, picks up a stick and makes his way over to a plastic log, lined with small holes. Breaking the stick in two, he pokes one end into a hole in an effort to extract honey that has been deposited by a conservation worker. His expression shows the tool’s use has been fruitful. But he is not alone. To his right another orangutan has turned half a coconut shell into a helmet, two others wrestle on the lawn, and another youngster scales a papaya tree. There are dozens of orangutans, all of which are about the same age. Just outside the compound, dozens of younger orangutans are getting climbing lessons from the Borneo Orangutan Survival Foundation (BOS) staff, while still younger orangutans are being fed milk from bottles in a nearby nursery. Still more orangutans—teenagers and adults—can be found on “Orangutan Island” beyond the center’s main grounds. Meanwhile several recently wild orangutans sit in cages. This is a waiting game. BOS hopes to eventually release all of these orangutans back into their natural habitat—the majestic rainforests and swampy peatlands of Central Kalimantan, on the island of Borneo. But for many, this is a fate that may never be realized.

Forest fires set by Borneo dam developer contributes to haze in Malaysia, Singapore

(08/17/2009) The developer of a massive hydroelectric project in Borneo plans to set fire to thousands hectares of logged over rainforest in the dam area, contributing to polluting haze already blanketing the region and raising the risk of forest fires in adjacent areas, reports a local environmental group. The Sarawak Conservation Action Network has learned that Sarawak Hidro Sdn Bhd, the operator of the Bakun Hydroelectric Power Dam project, is in the process of clear-cuting 80,000 hectares (200,000 acres) of rainforest set to be flooded by the dam. The remnants are being torched, in direct violation of Malaysia’s laws against open burning.

Borneo ablaze: forest fires threaten world’s largest remaining population of orangutans

(08/16/2009) Raging fires have broken out in the peat-swamp forests of Central Kalimantan, Indonesian Borneo, threatening the largest population of orangutans in the world. The fires were started by people but have spread uncontrollably due to the extreme drought that Borneo is currently experiencing as a result of El Niño conditions.

New fire record for Borneo, Sumatra shows dramatic increase in rainforest destruction

(02/22/2009) Destruction of rainforests and peatlands is making Indonesia more susceptible to devastating forest fires, especially in dry el Niño years, report researchers writing in the journal Nature Geoscience. Constructing a record of fires dating back to 1960 for Sumatra and Kalimantan (on the island of Borneo) using airport visibility records to measure aerosols or “haze” prior to the availability of satellite data, Robert Field of the University of Toronto and colleagues found that the intensity and scale of fires has increased substantially in Indonesia since the early 1990s, coinciding with rapid expansion of oil palm plantations and industrial logging.

Heart of Borneo conservation initiative at risk from Indonesian development plan

(02/04/2009) Indonesia’s Defense Minister Juwono Sudarsono is pushing a proposal to develop economic zones along the border between Malaysia and Kalimantan “as soon as possible” for national security reasons, reports the Jakarta Globe. The plan — which Juwono claims is to protect Indonesia’s sovereignty — would undermine the historic Heart of Borneo conservation initiative signed in 2007 by spurring massive expansion of logging, plantation development, and road construction in the biologically-rich region.

Borneo logging road puts rainforest, indigenous communities at risk

(10/22/2008) A 186-mile (300-km) logging road to the top of the Bario highlands in northern Sarawak puts the state’s increasingly rare natural forest at risk, warns the Borneo Resources Institute, a grassroots environmental group.