Study focuses on beef and soybean production at the expense of the Amazon rainforest.

Under the Kyoto Protocol the nation that produces carbon emission takes responsibility for them, but what about when the country is producing carbon-intensive goods for consumer demand beyond its borders? For example while China is now the world’s highest carbon emitter, 50 percent of its growth over the last year was due to producing goods for wealthy countries like the EU and the United States which have, in a sense, outsourced their manufacturing emissions to China. A new study in Environmental Research Letters presents a possible model for making certain that both producer and consumer share responsibility for emissions in an area so far neglected by studies of this kind: deforestation and land-use change.

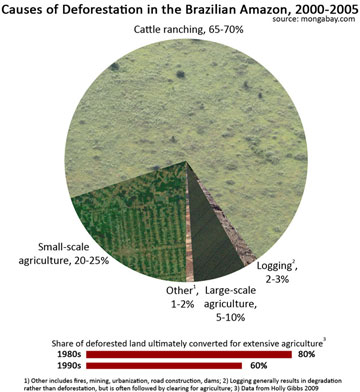

It’s not just China that is seeing emissions rise due to demand from other nations: deforestation of the Amazon in Brazil accounts for 75 percent of that nation’s emissions, but most of the products produced on deforested land, such as soy and beef, are exported to other countries in Europe, Asia, and Africa.

Pastureland and transition forest in Mato Grosso, Brazil (April 2009). Since 2003 Brazil has set aside 523,592 square kilometers of protected areas, accounting for 74 percent of the total land area protected worldwide during that period. Photo by Rhett Butler. |

“Brazil has some of the highest emissions from deforestation in the world and its exports of both soybeans and beef have grown dramatically in the last two decades,” David Zaks, lead author and graduate student at the Center for Sustainability and Global Environment (SAGE) at the University of Wisconsin, Madison told Mongabay.com.

Brazil’s high annual deforestation rates are currently supporting a massive agricultural industry that exports most of its product abroad: Brazil is the world’s largest exporter of both beef and soybeans. Between 1990 and 2006, exports of beef increased by 500 percent. The soy boom, which began in the 1990s, did not cause as much direct deforestation, but pushed cattle farmers and small-land holders deeper into the forest.

From 1990-2006, EU countries and Asian countries were the primary importers of Brazil’s soy, while importers of Brazil’s beef came from around the world, including Eastern Europe, the EU, the Middle East, Asia, Africa, and other South American nations. Yet so far none of these nations have had to pay a cent for the environmental damage, including high carbon emissions, caused by the deforestation of the Amazon.

Zaks and his team have proposed a model to change this. According to their study when a product is exported half of the emissions should be the responsibility of the producing country and half of the importing country and its consumers.

“There is no ‘right way’ to proportion emissions between consumer and producer, but we did not think that assigning the burden of emissions to either Brazil OR the importing country would be logical,” explains Zaks. “If emissions are assigned only to the importing country, there is a reduced incentive to decrease deforestation in the exporting country.”

|

He adds that the study “chose to split them 50/50 as more of an illustrative example than a definitive answer.”

The reasons behind sharing responsibility between producer and consumer is not just one of ‘fairness’, but rather the study argues that a model of shared emission responsibility will provide better incentives for reducing global deforestation. The model would give an economic advantage for countries which are able to produce agricultural goods not dependent on recent deforestation. The agricultural industry’s focus would be forced to shift, according to the paper, from deforestation of more land (extensification) to intensifying yields on already available land (intensification). This change would not only benefit the Amazon, but also the forests of Southeast Asia, where currently there is little economic incentive for agriculture crops, such as oil palm, to increase their yields.

“If agricultural commodities could be produced in another location, or use methods that have lower total carbon emissions, then demand would shift to those who could supply products with smaller carbon footprints,” Zaks says. “Of course this assumes that the price of carbon is greater than the potential profit of increasing production on newly deforested land. We provide a methodology to ‘internalize externalities’ in the hope that the full cost of products will eventually be accounted for in the price.”

Another part of the study’s model would ensure that both consumers and the producing company would take responsibility for the long-term consequences of deforestation.

“If the emissions from deforestation are allocated to just the first year of production then the products that are produced in subsequent years do not have to pay for the carbon embodied in their products, and they are ‘free-riding’. If the carbon emissions from deforestation are spread out over a longer time horizon, there is a limited disincentive to stop deforesting,” explains Zaks.

Forest clearing in Mato Grosso. Photo by Rhett A. Butler. |

Therefore the study picked a middle-of-the-road timeline—twenty years—and decided that the cost during that period should decline as it moves further away from the initial deforestation.

“The ’20 year decline allocation’ is a hybrid approach that assigns some of the responsibility of the carbon emissions from deforestation to the few years directly after deforestation at a higher rate than later years. This way, both the problems in the two other approaches are alleviated,” he says.

Using the 20 year decline allocation model, the study found that between 1990 and 2006 soybean exports from the Amazon were responsible for 128 TgCO2e (128 million metric tons equivalent of carbon dioxide—roughly the annual emissions from electricity generation in Florida or Pennsylvania) while cattle exports were responsible for 120 TgCO2e. Cattle was responsible for less export emissions, since more cattle was consumed locally. According to the study, the EU—the biggest importer of Brazil’s beef—imported a total of 61.8 percent of embodied (or indirect) emissions from 1990-2006 according to the study. The EU also imported 31.2 percent of embodied emissions from soy production in the Amazon. The cost of such percentages is not calculable as there is no set market price yet on carbon.

Of course, a carbon scheme such as this does pose difficult problems. One of these, especially when related to agricultural products, is how would adding a carbon tax on food affect the poor? Already the UN estimates that one billion people are going hungry.

“If this scheme were to be implemented, safety measures would have to be put in place to protect those who are food insecure,” says Zaks, but he adds that a carbon tax might eventually help bring down grain prices. “If prices increased on high-carbon items (livestock, grain grown for livestock), demand for those items would decrease, which would subsequently increase the supply of those grains and decrease their price (and increase availability to the poor). Of course, those are untested assumptions and an economic model would need to be used to test that case.”

Cattle herd in the Brazilian Amazon. Photo by Rhett A. Butler. |

Greenhouse gas emissions are, of course, not the only negative environmental impact from deforestation: biodiversity loss, decline of waterways due to a surfeit of nutrients, and local climate shifts such as rainfall decline have all been shown to follow clearcutting of rainforests. Zaks sees potential for adding these environmental impacts into the model at a later point, but more accounting of their impact needs to be done.

Of the ecosystem services provided by rainforests, “at this point, carbon emissions are the best quantified and also are closest to becoming widely monetized. There are some payment schemes that consider ‘baskets’ of ecosystem services, partly because the responses of other services are hard to measure. There are a lot of great research questions to be asked on how to incentivize reducing the impact of agricultural production on ecosystem services, and this paper just scratches the surface,” Zaks says.

The study concludes that the importance of this model is self-evident: “while many mechanisms have been proposed to decrease rates of deforestation in the Amazon, very few of them include the ultimate drivers of deforestation: consumers of agricultural products.”

CITATION: D.P.M. Zaks, C.C. Barford, N. Ramankutty, and J.A. Foley. Producer and consumer responsibility for greenhouse gas emissions from agricultural production—a perspective from the Brazilian Amazon. Environmental Research Letters. 4 (2009) 044010 (12pp). doi:10.1088/1748-9326/4/4/044010.

Related articles

Brazil pledges to restrain emissions growth

(11/15/2009) In a move that some observers say could provide a path forward on a future climate agreement that includes emissions cuts in developing countries, Brazilian President Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva said his country will aim to reduce emissions 14 to 19 percent below 2005 levels by 2020.

Brazil releases official Amazon deforestation figures for 2009

(11/13/2009) Deforestation in the Brazilian Amazon fell nearly 46 percent to the lowest annual loss on record in 2009, reported the Brazilian government Thursday.

Brazil to support REDD in Copenhagen

(10/28/2009) Brazil will conditionally support a proposed climate change mitigation scheme that will compensate tropical countries for preserving their forests, reports Reuters.

Brazilian beef giants agree to moratorium on Amazon deforestation

(10/07/2009) Four of the world’s largest cattle producers and traders have agreed to a moratorium on buying cattle from newly deforested areas in the Amazon rainforest, reports Greenpeace.

Brazil may ban sugarcane plantations from the Amazon, Pantanal

(09/18/2009) Brazil will restrict sugarcane plantations for ethanol production from the Amazon, the Pantanal, and other ecologically-sensitive areas under a plan announced Thursday by President Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva’s administration, reports the Associated Press.

Emissions from cerrado destruction in Brazil equal to emissions from Amazon deforestation

(09/15/2009) Damage to Brazil’s vast cerrado grassland results in greenhouse gas emissions equivalent to those produced by destruction of the Amazon rainforest, said Carlos Minc, the country’s Environment Minister.

Social causes of deforestation in the Amazon rainforest

(09/14/2009) Understanding the web of social groups involved in deforestation in the Brazilian Amazon is key to containing forest loss, argues a leading Amazon researcher writing in the journal Ecology and Society. Philip Fearnside of the National Institute for Research in the Amazon (INPA) reviews nine actors that have had significant roles in deforestation and reports differences in why they deforest, where they are active, and how they interact with each other.

Concerns over deforestation may drive new approach to cattle ranching in the Amazon

(09/08/2009) While you’re browsing the mall for running shoes, the Amazon rainforest is probably the farthest thing from your mind. Perhaps it shouldn’t be. The globalization of commodity supply chains has created links between consumer products and distant ecosystems like the Amazon. Shoes sold in downtown Manhattan may have been assembled in Vietnam using leather supplied from a Brazilian processor that subcontracted to a rancher in the Amazon. But while demand for these products is currently driving environmental degradation, this connection may also hold the key to slowing the destruction of Earth’s largest rainforest.

Activists target Brazil’s largest driver of deforestation: cattle ranching

(09/08/2009) Perhaps unexpectedly for a group with roots in confrontational activism, Amigos da Terra – Amazônia Brasileira is calling for a rather pragmatic approach to address to cattle ranching, the largest driver of deforestation in the Brazilian Amazon. The solution, says Roberto Smeraldi, founder and director of Amigos da Terra, involves improving the productivity of cattle ranching, thereby allowing forest to recover without sacrificing jobs or income; establishing a moratorium on new clearing; and recognizing the economic values of maintaining the ecological functions of Earth’s largest rainforest.

Amazon stores 10 billion tons of carbon in ‘dead wood’

(08/12/2009) Old growth forests in the Amazon store nearly 10 billion tons of carbon in dead trees and branches, a total greater than global annual emissions from fossil fuel combustion, according to scientists who have conducted the first pan-Amazon analysis of “necromass.”