Science, Economics, and REDD: Struggling for Balance

My friend Rezal Kusumaatmadja contacted me in July to ask if I could join him and some of his associates for a couple of days in the village Mendawai, located along the Katingan River in south central Kalimantan. The purpose of the gathering was to bring everyone in the group up to date on progress and challenges related to the Katingan Peat Conservation Project, as well as to give the group an opportunity to meet one another.

The Katingan Project aims to create a forest-based carbon containment facility defined and guided by REDD (Reduced Emissions from Deforestation and forest Destruction in the developing world) principles and methodology. Currently, nearly 25% of human-generated greenhouse gas emissions are caused by felling, burning and converting the world’s remaining primary forests. While areas surrounding the Katingan peat forest vividly express this statistic, Katingan is part of a growing strategy to reverse the trend. The Katingan project endeavors to transform conservation into a product that might offer strong competition against illegal logging and expansion of industrial agricultural plantations – whose practices cause enormous emissions of greenhouse gasses, as well as destroying biodiversity, depleting and polluting watersheds and corroding native cultures. The central purpose of REDD projects is to protect primary forest lands in order to inventory and store carbon, mitigate climate change and thus orient conservation to the marketplace through its creation of salable carbon offset credits. Certified carbon-offset credits derived from REDD sites can be sold in a rapidly growing voluntary carbon off-set marketplace. Additionally, they will likely extend their market value into an evolving international compulsory off-set marketplace which will take effect after the Kyoto Protocol expires in 2012.

|

|

Very conservatively, the Katingan site, by simply remaining undisturbed primary forest land through intentional prevention of exploitative strategies that would otherwise claim it, generates one-million Verifiable Emission Reductions (one VER equals one ton of sequestered carbon) per year. One forest-based VER today sells for between six and ten dollars. Additionally, Katingan also recognizes and cultivates other benefits provided by the conservation site, such as protecting biodiversity and watersheds, availing ancestral non-timber forest products for local use and broader trade, and creating eco-positive jobs for the site community. Many rare, charismatic species gorgeously manifest Katingan’s biodiversity. Hornbills, proboscis monkeys, clouded leopards and approximately 1500 orangutans populate the site. It is reasonable to judge that Katingan’s carbon-offset credits are distinguished by the project’s intentional cultivation of other environmental and social benefits and thus more valuable in a marketplace increasingly driven to become part of the solution to unprecedented social and environmental challenges. But our intuition precedes the logic of this observation. From our wholesale trade of rare species and life-sustaining watersheds for nice floors and tables, to the Great Pacific Garbage Gyre whose surface area exceeds two Texas’, the industrial world’s broadly misguided approach to conveying progress is rivetingly clear.

Rezal is a founder and the Managing Director of Starling Resources, “a consulting firm specializing in the design of solutions and opportunities to positively address social, economic and environmental concerns.” The Katingan Peat Conservation Project is an important part of a multi-strategy solution to climate change. Its success as a market opportunity requires only that we recognize obvious, critically important and irreplaceable values in natural systems. The health and quality of life of future generations depend on our adjusting the terms of our interaction with nature.

Convergence in Borneo

My schedule allowed three days and two nights to visit Mendawai. Mendawai isn’t easy to get to. It doesn’t have an airport and no roads lead to it. Much travel in Kalimantan occurs in narrow long boats with high and jutting prows to cut through sometimes sizable waves that can occur on wide, wind-swept rivers.

I awoke at four in the morning in Ubud, Bali to drive an hour or more to the airport in Denpasar to catch a 6:30 am flight to Jakarta. Bali seems most expressive of its extravagant gods in the very early morning. Raucous with birdsong, mist undulating through deep river gorges, the storied island’s compelling architecture vivid and not yet obscured by a dense population scrabbling for a piece of the modern world, nor by a nearly ubiquitous fever of tourist traffic that compels much of the scrabble. In Jakarta I rendezvoused with Agus Rofiqkoh, the director of Tropical Salvage production who had flown from Semarang. We flew together to Palankaraya, in Kalimantan. We met Asep and Ganden on the flight, two members of Starling Resources GIS mapping crew. Our group of four was met at Palankaraya airport by two other Starling Resources crew members, Panci and Aba.

|

|

The Starling team is jolly, quipping company who added much convivial spirit to a long ride. They are also extremely informed about the ecosystems and social environments in which they work. We drove through late morning and part of the afternoon more than four hours to a boat dock along the Mentaia River. Our 500 kilometer drive through south central Kalimantan revealed that much land viewable from the road had been reduced, by narrow-interested exploitation of forest resources, to expanses of deserted, white, nutrient-depleted soil dotted with scrubby plants. Ganden explained that topsoil in tropical forests is thin because growing conditions are optimal and thus competition for nutrients is so crowded and sharp that soil cannot accumulate appreciably. Lose the forest and intense rainy seasons soon wash away topsoil and, without a steady fall of tree and plant litter to replenish nutrients, precipitate desert conditions. Driving through the heart of Borneo, forest lines were far away but sharp against reaches of white. The road was notably smooth and wide for rural Indonesia, doubtlessly to facilitate the world’s unrestrained grab at Kalimantan’s diminishing natural bounty.

We reached the boat dock along the Mentaia River during late afternoon. A couple of guys were removing racks of hand-sized, sere fish that had cured beneath the day’s sun. An antlered deer head leaned at a side, awaiting apportionment, perhaps, into materials for Chinese medicines and global handicrafts. Winds chopped waves to anxious white caps. Various sized long boats were arrayed without clear order around the dock. Those unable to gain position directly against the dock were tied to one that was, or to one that was tied to one that was.

|

|

Boarding the long boat was a little steadier than boarding a canoe. Once in, we sat on floor boards elevated above the boats bottom and any water that might get in. I created rough comfort by positioning my backpack against a cross-board that braced the boat’s gunnels. The river appeared to be about a quarter mile across. We set out toward the other shore in a long diagonal and against the tossed waves. Two sea eagles soared above us, regarding the river casually. A deafening uncovered motor spewed bluish smoke, overwhelmed conversation and propelled us forward. The boat driver steered a wheel at the front and soon spray from a blunt fray of wind, waves and prow advised us to unfurl a tarp. At dusk we reached the mouth of a narrow canal dredged through deep peat. It had been cut during recent years of unmanaged, indeed unbridled, logging to facilitate a flow of loggers and logs into and out of the area, first in great abundance and lately in stunning depletion.

Some ways along into the canal we stopped at a rude dock and disembarked to wait for smaller boats to take us the rest of the way, as the dry season had made the water very shallow in places. We waited for the boats at a spare food stall, or “warung,” operated by a native Dayak family. We sipped sweet coffee and chewed delicious campfire-roasted salted peanuts; several of us tried to answer a bird’s lonely haunting inquiry at dusk. “Where am I?” it seemed to wonder. The warung’s proprietor explained they had settled into the outpost some twenty years ago to take advantage of a logging boom. They followed the forest cut until the cost of gas to travel by boat to and from the cut-line grew too high to make economic sense. Currently, they are growing vegetables and fishing, and when possible selling food and drink at their warung and charging fees for boat rides. Some neighbors are trying to grow rubber trees.

It was dark when smaller boats arrived. We boarded two to a boat, Agus and I in the front boat. We motored into the dark, guided by a small but strong-beamed light affixed to the tip of the prow. As soon as we started, several bats flew into the light beam, hurtling just ahead of the fast boat, apparently taking advantage of the light’s allure to insects. Twice, a kind of night raptor tore from the canal’s bank and seized a bat made careless by its predation. An odor of burning, musty wood was thick through the canal. The canal’s centuries old peat walls, their dense entanglement of tree roots, appeared primeval and haunting in the glancing light.

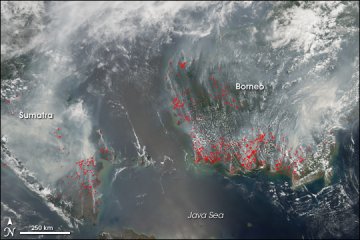

2006 fires in Borneo and Sumatra Smoke from agricultural and forest fires burning on Sumatra (left) and Borneo (right) in late September and early October 2006 blanketed a wide region with smoke that interrupted air and highway travel and pushed air quality to unhealthy levels. This image from the Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) on NASA’s Aqua satellite on October 1, 2006, shows places where MODIS detected actively burning fires marked in red. Smoke spreads in a gray-white pall to the north. NASA image created by Jesse Allen, Earth Observatory, using data provided courtesy of the MODIS Rapid Response team. |

When we rounded a bend the source of smoke became clear. Along the canal bank a long menacing sneer of red coals burned beneath the top soil: a peat fire. In a healthy peat forest that possesses dense tree canopy to retain moisture and regulate ground temperature, it’s very difficult for fire to spread. If you remove the forest’s protective canopy, then deep dead roots and exposed peat become a tinder in the dry season, awaiting combustion. Peat fires, often intentionally set to hasten conversion of land to agricultural purposes, usually oil palm, are why Indonesia is the world’s third largest emitter of carbon, behind China and the United States.

A climax to the bizarre wonderment of our ride through the canal occurred when an enormous wild boar charged into the river, in front of our boat, close enough to me so that I adjusted my position to a ready squat, in case of a collision. Water stirred from its commotion splashed me in the face. In the beam it appeared very riled, perhaps driven to fear or anxious confusion by the peat fires. I tried to call my wife, Eli, and two young children, Maddie and Rowan, in Bali to report this encounter but no signal was available.

After traveling through the canal and crossing the Katingan River, to which the canal was connected at the other side, we arrived at Mendawai Village at about ten pm. A group had arrived before us that included Rezal, Taryono, Starling Resource’s field crew leader, Andrew Wardell, the Director of the Clinton Climate Initiative, Brer Adams, Senior Manager for Utilities and Climate Change with the MacQuarie Group, Dharsono Hartono, Managing Director of PT. Rimba Makmur Utama ( First Prosperous Forest) and the Katingan project’s principal investor, Kirk Lange, Head of Research and Development at PT. Rimba Makmur Utama, and Amy Chew, a Senior Correspondent with the New Straits Times, published in Kuala Lampur.

Emerging Vision

We walked up one of Mendawai’s only three or four roads. All of the roads are graded dirt and very pot-holed from the previous rainy season. We stopped at a warung where some of the group sat, greeted them and ordered from the option of chicken soup or fried chicken. Earlier in the day, several in the group had flown back-and-forth in a small plane over Katingan. Some of the site’s boundaries are marked by rivers. Others are encroached on by oil palm plantations, artisanal gold mines and illegal logging patches. These three rudely narrow valuations of natural resources are ripping the heart out of our world’s ancestral biodiversity and extensively degrading global ecological integrity and the prospect of a reasonable quality of life for our children.

|

|

Under an intense canopy of stars and amidst competing choruses of nocturnal creatures, Andrew Wardell eloquently reminded us that peat forests are the world’s richest forest-based carbon storage – the peat layer reaching some twelve meters down in many parts of Katingan. Their destruction over recent decades has released billions of tons of carbon into the atmosphere, accelerating climate change. He described peat fires that burn for months uncontrolled beneath the ground – and undetected until they reach a forest edge where mature standing trees begin to fall over because fire has cut through their root systems.

Within the next hour or so of conversation, it became clear to me that the group gathered at Mendawai shared a common vision, shaped by irrefutable logic wrought by climate change, to reinterpret the defining relationship between humans and our natural environment. The vision integrates conservation initiatives of enormous scale with market principles.

I slept deeply on a thin mattress laid on the floor of a small room in Mendawai’s only losman. As no bed cover was provided, I awoke early in the morning to lay an extra shirt across my bare feet. A little later, at about 5 am, an extremely loud morning call to prayer, azan, blared from a mosque located directly across the road from the losman. It sounded burdened and bedraggled, in contrast to other calls to prayer I’ve heard, whose mellifluousness can coax an agnostic from his bed before sunrise, to his knees and seeking redemption. Yet the sound seemed fitting to Mendawai’s circumstances.

A setting could hardly better answer the description “in the middle of nowhere.” Yet, by 6 am I was seated on an old wooden bench, listening to a fantastic racket of birdsong and sipping sweet tea with Andrew, Dharsono, Brer and Rezal, all of them possessing expertise in understanding climate change and actively involved in shaping large forest-based mitigation responses. They are among the vanguard of innovative problem solvers who envision a world where respect for natural systems is an integral component of economic viability and success.

Oil palm plantation in Central Kalimantan. Photo courtesy of Rezal Kusumaatmadja |

Andrew leads teams in formulating methodologies to measure and monitor forest-based carbon sinks. He also manages stakeholders so that all might duly benefit from a site’s development. Currently he manages projects in Cambodia, Viet Nam and Indonesia. He is a strong proponent of a REDD response to climate change. REDD was created because most of the world’s remaining old-growth tropical forests, the forests richest in carbon containment, are located in developing countries. Until the recent debate – precipitated by climate change – about integrating carbon responsibility with our economics, most of the world’s tropical developing countries served as natural resource depots which industrialized countries could recklessly exploit to help sustain their invention, prosperity and growth. The traditional model of exploitation, though, has significantly paused as a struggle escalates to redefine value of the world’s natural resources. But exploitation is not patient.

Mendawai’s Uncertain Future

After breakfast, we walked to Mendawai’s government administrative building. As with many government entities in Indonesia, its presence seems out-sized relative to the location’s small population and spare infrastructure. It is the biggest building in the village and contains many offices populated by officials wearing pressed uniforms emboldened by prominent epaulettes. Approximately ten-percent of Indonesia’s two-hundred and forty million citizens are on a local, provincial or federal payroll. Compare that to the United States where only four or five percent of the population work for a government sector. It would not seem so disproportionate if Indonesia boasted an exemplary civil infrastructure which skilled government officials routinely and assiduously maintained and improved. Instead, Mendawai serves as a telling microcosm for Indonesia’s political and economic challenges. The village is ramshackle, sagging from tropical dissolution, while the government administrative offices remain tidy, its many pairs of epaulettes starched and vigilant, awaiting opportunity.

Most government employees in Indonesia aren’t paid enough to live on and are, in fact, expected to finesse a living income by profitably asserting power attained from their position. Also, government employees often incur debt from having borrowed money to buy their position. Money and connections supplant merit; reasonable compensation depends on irregular exploitation of legal and illegal business revenue streams: when people speak of “systemic corruption” these are conditions from which it arises.

Clearing of peat forests in Central Kalimantan.

|

Systemic corruption in Indonesia must change and can change beginning with a serious and committed effort by the international community to engage Indonesia as a partner in fee-based, forest carbon containment. A first step might be to ensure the Ministry of Forests hires Indonesian personnel according to merit and offers them compensation appropriate to affording a reasonable standard of living.

During decades of unrestrained timber harvests around Mendawai, opportunity availed itself to all. The forest’s bounty of timber seemed a limitless sea. Mendawai is founded on that period of exploitation. During those days, a harvest crew leader could make $1000 a month, sawyers $300-$400 a month – enormous compensation, at that time, for unskilled and little-educated Indonesians. Results from unregulated logging of forests whose wood attracted wide international demand are what you would expect. Today, all the low-hanging fruit is gone and expanses of land appear obliterated. Also, continued harvests have been greatly staggered by a logging moratorium imposed by the government in 2005, when they began to take seriously the prospect of collecting higher revenues from their forests’ managed carbon storage.

During the past few years, Mendawai’s population has declined by about half, to approximately 1500 citizens. Incomes, patched together from small-holder agriculture, fishing, boat-building and whatever other opportunity might pass up or down the river, are a fraction of their previous timber-era standards. Tropical rains and sun beat down, modern conveniences purchased during flush times show stress, people wait.

Arrayed in a spacious office, we listened to an articulate government spokesman describe the direness of Mendawai’s situation. He explained they were interested in examining any potential that might improve their economic condition. He suggested we could gain the community’s undivided attention to our conservation and carbon-containment vision if we built a road between Mendawai and a more economically strategic place.

Peat Forests Versus A World of Desire

|

|

Peat forests are the richest forest-based carbon sinks in the world. Conserving the integrity of remaining peat forests and, if possible, expanding them is very important to mitigating climate change. Scientists who are expert in understanding forests’ roles in regulating climate have warned that further degradation of existing primary forest lands will prove a strongly enabling piece to catastrophic climate change. Industry fells trees in Kalimantan’s peat forests to generate wood material favored for structural beams, flooring and furniture. Plenty of ecologically sustainable substitutes exist to replace trees harvested from Kalimantan’s peat forests, but desires are hard to subdue.

A market is opportunity to answer material need or desire through trade. In our wealth-obsessed era, markets are often exploited, without due consideration of broader consequences, to acquire excess. When a market’s broader consequences become untenable and logic of serious regulatory correction fails to respond, what strategies might be employed to oppose it? Elective self-restraint has not yet gained popular momentum in “the commons.” The majority of us respond to immediate alarm; the closer alarm comes to compromising our well-being, the more responsive we become. For too many of us, enough response arises only after our well-being has been chafed or battered. Science has modeled consequences of climate change. They are alarming. In many models, anticipated expressions of challenge are exceeded by reality. “Feedback loops” are asserting magnitudes of negative change – disastrous change – at a much faster pace than many scientists projected. These are some common projections based on widely accepted climate change models: By 2030, after the polar ice caps have significantly melted, approximately 2000 of Indonesia’s some 16,000 islands will have been swallowed by rising seas. Millions – tens of millions? Hundreds of millions? – of people living in coastal communities around the world will have been displaced. To where? Provoking what disruptions? How will the seas’ rising temperatures and disrupted chemistry affect marine ecosystems and food-stocks? How will changing weather patterns affect terrestrial ecosystems and food-stocks? Rising temperatures and extended dry seasons caused by climate change have sharply increased incidents of record fires throughout the world. How many records will be broken by 2030? Global population will be pushing 8.5 billion by then, unless fierce competition for diminished natural resources pares that number through multiplying conflicts and wars.

We are spiraling into an era of the unthinkable. Is it possible for us to respond to an atypical issue with atypical efficiency of logic? Might capitalism’s principles – and guiding instincts – be rapidly modified to support a natural world of which we are inextricably a part?

I know some well-educated, good-hearted people for whom growing wealthy and surrounding themselves with material signals of wealth is a life-defining objective. Capitalism encourages this perspective but history reveals the perspective has ever existed prominently in many cultures. If desire to accumulate material excess is an ingrained characteristic of many of us, might it be possible to redefine the signals of wealth so that our pursuit of them adds to the common good? Could we reinterpret values of goods so that the values accord with sustaining the broader quality of our social and natural environments? In such a system, for example, gold, the world’s perceived default safe investment, might sharply decline in value. We would replace our perception of gold with its reality: mining gold destroys vast areas of important ecosystems; it pollutes watersheds with toxic chemicals such as cyanide and mercury; because we have decided to assign it high and very liquid value in trade, gold is largely compiled as bricks and coins and worked into jewelry rather than applied to constructive use. We might choose to apply a stigmatization to gold that it has earned through a long, well-documented history of influencing environmental destruction, cultural upheaval and social conflict. Is it possible to decide not to assign gold high value? In doing so, we would choose a better future for ourselves by helping to protect the integrity of natural environments.

|

|

Also, in a holistically considered world, maybe cultivating a forest garden in your back yard, using native species and organic techniques, could generate valuable tax credits through its carbon storage, contribution to protecting a watershed and maintenance of biodiversity. Adding forest gardens could raise property values if we simply chose to acknowledge and support their value. People might seek and compete for an excess of this sort of wealth – cultivating brilliant, expansive, luxurious forest gardens. Gold pebbles, left over from the ore’s price-crash, when people shrugged and decided it was wildly over-valued for no good or useful reason, might be mixed with other types of recycled rock material to form a gravel path through the garden.

Instead, as consequences of climate change grow clearer and more ominous, gold is priced historically high and trees harvested from Kalimantan’s peat forests are still perceived by many as being more valuable turned into objects than they are for their multiple benefits as part of a forest ecosystem. The trajectory of our material covetousness has arrived at a juncture where it might begin to contradict Darwin’s well-regarded theories about survival. Even against the full force of science’s findings and vivid, enduring, negative consequences that undermine our common good, we remain deeply challenged to restrain consumer excess.

Tropical Salvage

|

|

“Tropical Salvage” is a part of Rezal’s and Dharsono’s visionary Katingan collaboration. Tropical Salvage integrates business with best environmental and social practices because we understand the business community must join the lead in answering unprecedented challenges to environmental and social integrity. In spite of cynicisms’ prodigious draw – one particularly affecting in an era when the world’s leading power, my government, bails out financial institutions that have financed and grown rich from practicing a variety of capitalism that trails a century-long wake of global-scale environmental devastation – I choose optimism and believe a form of economic activism will recover and deliver us from generations of arrogance. I believe this because climate change leaves no other rational choice and because I believe an emotional portal unlocked by caring for children, and offering no quarter to cynicism, fortifies our intention with redeeming grace. I believe that, once bailed out, the same financial institutions will invest strongly in businesses that enable environmental recovery, as these many emerging businesses modeled after common good capitalism are the future’s best, if not single, hope for a reasonable quality of life.

And make no mistake, it is largely the “developed world’s” responsibility to initiate and lead this economic gambit. Indonesia well reflects challenges to the “developing world” in assuming roles of leadership to advance positive change. Restricted by economic circumstances, most Indonesians haven’t had the opportunities or experience to interpret their choices in the context of broader consequences – whether locally or globally. Starkly, they need money, they need food, they need health care and, in the case of Mendawai, they need a road connecting their village to higher value markets. That’s the breadth of vision their experience allows them. If felling, legally or illegally, some peat forest trees answers their spare needs for a day, or a week, then, without the existence of alternative work to answer those needs, the forests will fall.

|

|

In Mendawai, Tropical Salvage can help to abate this logic. It can provide jobs salvaging wood from rivers and deconstructing defunct, dilapidated milling warehouses. The work will reduce illegal logging and poaching, as well as create a platform from which to communicate a conservation perspective that is critical to protecting Katingan and thus to adding a piece to restoring global ecological integrity. We will work in concert with local and federal government and forestry administrators, with the project’s eco-entrepreneurs and investors, with carbon scientists and forest mappers, with wildlife biologists and ethno botanists, with community organizers and forest product industry spokespeople, with fishermen and rattan gatherers. We will be part of an integrated strategy to become part of the solution.

Tropical Salvage products are a fruit of positive change. We build furniture from discovered and deconstructed woods that are largely perceived as waste, applying building techniques to convert material irregularities into added value. Also, when consumers buy Tropical Salvage products, in addition to acquiring exceptional value, they directly contribute to forest conservation and restoration projects in Indonesia, including, we hope, the Katingan site. We make positive impact consuming convenient; we practice common good capitalism. While we vigilantly attend to a business bottom-line, accumulating material wealth is not a specific objective. Instead, we aim to contribute to salvaging a peaceful relationship between people and tropical environments. Social and environmental health is the new wealth. Should we succeed at establishing and growing our part of the solution, no amount of gold can compete with the legacy.

Bringing the Forest Home

|

|

On the way out I silently inventoried potentials for salvageable wood in Kalimantan. Limbs, logs and whole trees litter the banks of the Katingan and Mentaia rivers. Walls of defunct milling warehouses fade and buckle along the shores. The prow of an enormous log-hauling ship protrudes from the Katingan River’s surface where excess sank it. Loggers I spoke to in Mendawai remembered cutting all the trees standing in the way of targeted stands and leaving off-species behind; they confirmed a common logging practice of sending only tree bodies to the marketplace and leaving their limbs in the forest to burn or float away in floods. Based solely on visible salvage potential, there are decades of work, here, transforming waste into high value.

Crossing the Mentaia, we encountered a ship hauling a pile of newly milled logs, headed down-river to the sea and our world of commerce. The trees were taken from Borneo’s far and receding wild interior, where, I recently read, some members of the last nomadic Penan tribes are answering incursions on their ancestral lands from logging and oil exploration with blow guns and bows and arrows. Diameters of some of the logs were greater than my six-foot height.

As we approached a dock where we would meet our ride back to Palankaraya, we passed several tall, simply-constructed, white buildings with many small rectangular portals. I recognized them as towers built to attract swallows whose nests are the anchor ingredient of a soup widely favored in China. Many swallows flew around the buildings, some entering and some exiting. A racket of bird squawk and chatter sounded distinctly over the boat motor’s din. The deafening bird sounds suggested there were many more birds in the buildings than outside. I tapped Taryono’s shoulder, and with my other hand pointed at the towers. “Jutaan burung walet!” (“Millions of swallows!”) I exclaimed, pointing to the buildings. He shook his head. “Bukan!” (“No, that’s not right!”). “Mereka pakai pita suara!” (“They use a sound-track!”).

Tim O’Brien, founder of Tropical Salvage. Photo by Edward Wolf |

As I listened to ersatz swallow-shrieking, it occurred to me that the sound-track was likely calibrated to sound optimally attractive to the species of swallow sought for its edible nest. I’m struck at least as often by my species’ genius as I am by its idiocy. I believe our genius has, like Las Vegas’ gambling parlors, an edge. As if to punctuate the thought, my phone vibrated in my pocket. Still very deep in Borneo’s hinterland, I could already call my aging mother in Chicago to ask how her garden is growing.

My daughter, Madeline, answered my “Hello” to tell me she “loves me like a whale.” It’s a thing we say that characterizes the size of our feelings. I imagined the sentiment ricocheting between signal towers across stretches of land and sea. What genius we’ve employed to be able to instantly cast our audible love across the world. And what genius is our capacity to love. It will prevail.

Related

Salvage logging offers hope for forests, communities devastated by industrial logging

(12/04/2008) As currently practiced, logging is responsible for large-scale destruction of tropical forests. Logging roads cut deep into pristine rainforests, opening up once remote areas to colonization, subsistence and industrial agriculture, wildlife exploitation, and other forms of development. Timber extraction thins the canopy, damages undergrowth, and tears up soils, reducing biodiversity and leaving forests more vulnerable to fire. Even selective logging is damaging. Nevertheless demand for wood products continues to grow. China is expected to import more than 100 million cubic meters of industrial roundwood by 2010, much of which will go into finished products shipped off to Europe and the United States. As much as 60 percent of this is illicitly sourced. Meanwhile in Brazil domestic hunger for timber is fueling widespread illegal logging of the Amazon rainforest. Armed standoffs between environmental police and people employed by unlicensed operators are increasingly common. Tropical Salvage, a Portland, Oregon-based producer of wood products, is avoiding these issues altogether by taking a different approach to meet demand for products made from high-quality tropical hardwoods. The company salvages wood discarded from building sites, unearthed from mudslides and volcanic sites, and dredged from rivers in Indonesia and turns it into premium wood products. In the process, Tropical Salvage is putting formers loggers to work and supporting a conservation, education and reforestation project on Java.

Related articles