In conserving its forests while its growing export-oriented wood products industry, Vietnam outsources deforestation to Laos, Cambodia, and China.

|

|

Taking a cue from its much larger neighbor to the north, Vietnam has outsourced deforestation to neighboring countries, according to a new study that quantified the amount of displacement resulting from restrictions on domestic logging.

Like China, Vietnam has experienced a resurgence in forest cover over the past twenty years, largely as a result a forestry policies that restricted timber harvesting and encouraged the development of processing industries that turned raw log imports into finished products for export. These measures contributed to a 55 percent of Vietnam’s forests between 1992 and 2005, while bolstering the country’s stunning economic growth.

But the environmental benefit of the increase in Vietnam’s forest cover is deceptive: it came at the expense of forests in Laos, Cambodia, and Indonesia. Authors Patrick Meyfroidt and Eric F. Lambin of the Universite Catholique de Louvain in Belgium calculate that 39 percent of Vietnam’s forest regrowth between 1987 and 2006 was effectively logged in other countries. Half of the wood imports into Vietnam were illegal.

Conversion of old-growth forest for a rubber plantation in Northern Laos in January 2009. This particular project is run by a Chinese firm, but in eastern Laos Vietnamese companies are significant players in the timber trade. |

“Vietnam protected its forests and developed its economy by exporting its deforestation to neighboring countries,” the authors write, noting that the apparent “leakage” — an increase in deforestation in one region caused by reduction of deforestation in another — is “a major challenge in policies aimed at protecting forests and mitigating carbon emissions”.

Indeed, international leakage has been a chief concern under a proposed mechanism for mitigating greenhouse gas emissions by reducing deforestation and degradation (REDD). The authors say that in Vietnam’s case, where illicit deforestation in neighboring countries has fueled domestic economic growth, leakage is particularly complex. Should Vietnam be penalized for illegal forest clearing in Laos, Cambodia, and Indonesia? If so, should it also receive carbon credits for the carbon stored in the wood products it exports? Or should the carbon emissions burden ultimately fall on the consumer, likely a furniture buyer in an industrialized country?

The authors don’t take a position, but they do argue that any REDD mechanism will need to somehow account for leakage.

“When policies—such as may be implemented through a REDD scheme—aimed at protecting forests lead to a decrease in harvests without accompanying measures to control wood consumption and/or increase wood production from plantations and processing efficiency, then leakage abroad will most likely occur,” the authors write. “Leakage should thus be directly addressed in forest protection policies.”

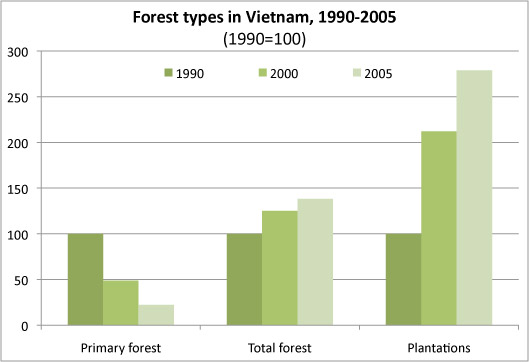

But there is another twist in the story for Vietnam should it seek compensation via a REDD scheme for regrowing its forests. While the country has seen a dramatic recovery in net forest cover, its primary cover has been dramatically reduced. According to the U.N. Food and Agriculture Organization Vietnam lost a staggering 78 percent of its old-growth forests between 1990 and 2005. Given that old-growth forests store more carbon than plantations and regenerating secondary forests, the emissions resulting from the transition from old to new forests have been substantial. This raises another question: should logging of old-growth forests in Vietnam continue — whether legal or illegal — will emissions from this degradation be figured into a REDD compensation scheme?

Change in primary forest, total forest, and plantation cover

in Vietnam between 1990 and 2005, using FAO data

Meyfroidt, P., & Lambin, E.F. (2009). Forest transition in Vietnam and displacement of deforestation abroad. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences DOI: 10.1073/pnas.0904942106

Malaysia’s rainforests being insidiously replaced with plantations of clones

(07/20/2009) Rainforests once managed for selective logging in Malaysia are now being are clear-felled and replaced with latex-timber clones, rubber trees that yield latex and can be harvested for timber, reports the Malaysian Star. Up to 80 percent of Malaysia’s remaining forest cover could be at risk. Journalist Tan Cheng Li reports that permanent forest reserves in Selandor and Johor have already been cleared for rubber plantations, while other reserves are now being targeted. Permanent forest reserves are forest areas that have been set aside for selective logging under sustainable forest management. They account for 82 percent of Malaysia’s remaining forest cover.

Asia’s conversion of forests for industrial rubber plantations hurts the environment

(05/21/2009) Policies promoting industrial rubber plantations over traditional swidden, or slash-and-burn, agriculture across Southeast Asia may carry significant environmental consequences, including loss of biodiversity, reduction of carbon stocks, pollution and degradation of local water supplies, report researchers writing in Science. Conducting field work in the Xishuangbanna prefecture of China’s Yunnan province and assessing broader regional trends, Alan Ziegler of the National University of Singapore and colleagues argue that policies favoring agricultural intensification over small-scale slash-and-burn have encouraged the rapid expansion of rubber plantations across more than 500,000 hectares (1,930 square miles) of montane forest in China, Laos, Thailand, Vietnam, Cambodia, and Myanmar. Despite widespread perception among authorities that “swidden cultivation is a destructive system that leads only to forest loss and degradation”, the researchers found that the transition to industrial plantations has not necessarily been a boon to the environment.