How can bringing healthcare to local villagers in Uganda help save the Critically Endangered mountain gorilla? The answer lies in our genetics, says Dr. Gladys Kalema-Zikusoka, wildlife veterinarian and director of Conservation through Public Health (CTPH).

“Because we share 98.4% genetic material with gorillas we can easily transmit diseases to each other.” Therefore, explains Kalema-Zikusoka “our efforts to protect the gorillas will always be undermined by the poor public health of the people who they share a habitat with. In order to effectively improve the health of the gorillas we needed to also improve the health of the people, which will not only directly reduced the health threat to gorillas through improvement of public health practices, but also improved community attitudes toward wildlife conservation.”

This is CTPH’s mission in a nut shell: save wildlife by improving local human health and hygiene. It’s a win-win concept that so far has been ignored by major conservation organizations.

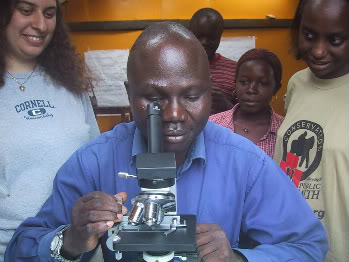

Kalema-Zikusoka at Hard edge between the forest. |

It was an outbreak of scabies skin disease outbreak among the mountain gorillas, which killed an infant gorilla and sickened the whole group, that led Kalema-Zikusoka to establish CTPH. When the disease was eventually linked to the neighbouring human villages, Kalema-Zikusoka saw a way to both help gorillas and people.

Now CTPH provides health services and education in hygene to local people while monitoring gorilla health.

“Park staff collect fecal samples from gorillas every week and when they range outside the park,” Kalema-Zikusoka says. “Results from the fecal analysis are shared with the livestock and human health sectors to be able to better detect disease transmission at the human/wildlife/livestock interface.”

Yet since its inception, CTPH has moved far beyond monitoring health of both groups for possible disease. They have worked long and hard to give the local people a better life, including education and economic opportunities. CTPH has begun a program to encourage family planning (Uganda has one of the world’s highest population growth rates); they have built a telecentre so locals can have access to the Internet and therefore the wider world; they have begun computer courses at the center; and the organization has promoted ecotourism in the area as an alternative to poaching.

CTPH’s successes have not always been easy. Kalema-Zikusoka says that one of the difficult tasks has been receiving funding for an organization that straddles the line between public health and conservation.

“Sometimes when we go to human health donors they say that we are animal people or when we ask conservation donors for funds to support community public health they say that this is public health not conservation,” she says.

Examining gorilla fecal sample. Photo courtesy of CTPH. |

Yet CTPH has largely overcome this confusion. “We have made great progress in explaining this approach and received support from donors who see CTPH as a cutting edge approach to promoting wildlife conservation and integrated conservation and development initiatives (ICDs).”

It is clear that CTPH is beginning to be recognized for its innovative and effective approach: Dr. Gladys Kalema-Zikusoka won the Whitley Gold Award for grassroots nature conservation, i.e. the ‘Green Oscars’, this year.

In a September interview with mongabay.com, Kalema-Zikusoka spoke about winning the Whitley, combining public health and conservation, and the importance to conservation of providing education and technology to local communities.

Kalema-Zikusoka will be presenting at the upcoming Wildlife Conservation Network Expo in San Francisco on October 3rd.

INTERVIEW WITH DR. GLADYS KALEMA-ZIKUSOKA

Mongabay: What is your background?

Gladys Kalema-Zikusoka: I am a wildlife veterinarian with public health field research experience in and around protected areas in Africa. I started my career with wildlife, when reviving a wildlife club, the Kibuli Secondary School Wildlife Club, at high school in Uganda in 1988, which focused on conservation education and had not been functioning for many years. This experience made me want to become a vet who works with wildlife. In 1996 I became the first veterinarian in the Uganda Wildlife Authority, and set up the veterinary department. During this time I led a team that investigated the first scabies skin disease outbreak in mountain gorillas traced to people living around the park. This was another turning point in my life where I felt that I also needed to improve the public health status of communities bordering protected areas who are important stewards of wildlife.

Mongabay: Most people wouldn’t necessarily link public health concerns with conservation. What is the connection?

Infant mountain gorilla dead from scabies. Photo courtesy of CTPH. |

Gladys Kalema-Zikusoka: I got involved in public health when investigating a scabies skin disease outbreak in mountain gorillas of Bwindi Impenetrable National Park, which resulted in the death of an infant and sickness in the rest of the group that only recovered with Ivermectin anti-parasitic treatment. The outbreak was eventually traced to people living around the park who have inadequate health care, hygiene practices, and information on diseases that can spread between animals and people (zoonoses). Because we share 98.4% genetic material with gorillas we can easily transmit diseases to each other. This made me realise that our efforts to protect the gorillas will always be undermined by the poor public health of the people who they share a habitat with. In order to effectively improve the health of the gorillas we needed to also improve the health of the people, which will not only directly reduced the health threat to gorillas through improvement of public health practices, but also improved community attitudes toward wildlife conservation. In particular the communities around Bwindi and other great ape protected areas—where there is ecotourism—benefit directly from having healthy gorillas. When we conducted health education workshops on the risks of human and gorilla disease transmission, we found that the communities that were benefiting from tourism through job creation, revenue sharing and small businesses, were very willing to listen to what we had to say, because they saw that if they are healthy and hygienic this will contribute to sustaining the gorilla populations, and a source of income from gorilla ecotourism.

Mongabay: How has your training as a vet impacted your work with your organization Conservation through Public Health (CTPH)?

Signs of mountain gorillas: banana crop destroyed by the mountain gorilla. Photo courtesy of CTPH. |

Gladys Kalema-Zikusoka: My training as a vet has impacted my work at CTPH, where the programs are designed around a background of veterinary medicine and conservation medicine. We have three integrated programs: wildlife health monitoring, human public health and information, education and communication. In the wildlife health monitoring program I have the opportunity to implement what I was not able to as UWA vet where my main job was to attend to emergencies with sick wildlife and disease outbreak, and did not leave me enough time to set up long term systems to monitor health of the wildlife and establish an early warning system for disease outbreaks. My veterinary training has enabled CTPH to set up a disease monitoring and surveillance system where park staff collect fecal samples from gorillas every week and when they range outside the park. Results from the fecal analysis are shared with the livestock and human health sectors to be able to better detect disease transmission at the human/wildlife/livestock interface. My veterinary training also enables us to carry out wildlife interventions, such as immobilizations and post-mortems when the need arises.

Mongabay: The public is aware of many examples of diseases passing from humans, but what are some examples of diseases passing from humans to animals, such as gorillas?

Gladys Kalema-Zikusoka: Examples of diseases passing from humans to great apes are scabies passing from local community members to gorillas in Bwindi Impenetrable National Park and respiratory viruses passing from researchers to chimpanzees in the Tai Forest in Ivory Coast.

Mongabay: Much of your work has been with gorillas (and the people living near them)—have you also worked with other species?

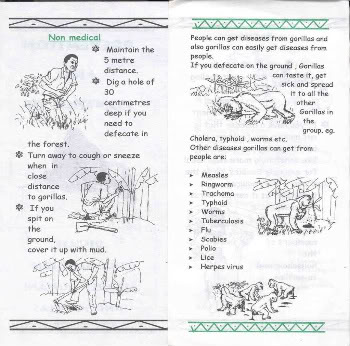

Health sign posts from CTPH. Photo courtesy of CTPH. |

Gladys Kalema-Zikusoka: I have also worked with other species, particularly when I was the veterinary officer for Uganda Wildlife Authority dealing with animal emergencies, disease outbreaks, translocations and reintroductions and problem animals. The mandate of CTPH involves us working with all the wildlife, and currently we are setting up a savannah ecosystem model in Queen Elizabeth National Park based on the forest ecosystem model in Bwindi, where we are dealing with issues of disease transmission between wildlife and livestock. We work with chimpanzees in the forest ecosystem, and other species in the savannah ecosystem, including buffalo, Uganda kob and warthogs to see if they are sharing diseases, such as Tuberculosis (TB), brucellosis, foot and mouth disease, anthrax and African Swine Fever with cattle, goats and pigs.

Mongabay: How important is tourism—such as visitors coming to see the gorillas—to the communities you work with?

Gladys Kalema-Zikusoka: Tourism is very important for the communities because it provides a sustainable source of income from gorilla ecotourism that helps to prevent the communities from going into the park to poach and collect firewood. Uganda Wildlife Authority set up a community conservation department to ensure that the communities bordering the park benefit and become active stakeholders in wildlife conservation. Around Bwindi, 90% of the rangers/trackers are from the immediate communities and former poachers were employed as trackers; 20% of the park entrance fee is shared with the communities bordering the park and used to build schools, clinics and roads; and most importantly people are benefitting from small businesses selling crafts, food and offering accommodation to tourists that goes directly to the local entrepreneurs in the community. Some schools such as Buhoma Community Primary School (former Bwindi Orphans School) were built through tourists sponsoring kids to go to school, so these children are growing up understanding the importance of gorillas in sustaining their future livelihoods.

Mongabay: When working to save species like gorillas why do you believe it is important to also improve the lives of local people?

CTPh brochure in local language. Photo courtesy of CTPH. |

Gladys Kalema-Zikusoka: When working to save gorillas, it is important to also improve the lives of the local people because they need to see tangible benefits that can be derived from protecting the gorillas. If they are poor they will only be thinking of today’s needs and not tomorrow’s future for their children. On top of improving the health of the communities, CTPH is also promoting family planning because Uganda has one of the highest population growth rates of 3.3% and fertility rate of 7.1. Furthermore, Bwindi has one of the highest population densities in Africa of 200 to 300 people per square kilometre and an average size of 10 children per family, making it very difficult for their parents to send them to school and give them basic primary health care. This in turn leads to the children not being able to get jobs resulting in poaching and illegal harvesting, as well as harbouring many preventable infectious diseases that could also harm the gorillas.

Mongabay: Your organization has opened a Telecenter in Bwindi. Can you tell us about the center and how has it helped conservation and local health?

Gladys Kalema-Zikusoka: The telecentre in Bwindi is helping to address the problems of poverty, isolation, poor health practices, lack of knowledge on sustainable environments, and limited access to education and job training in and around Bwindi Impenetrable National Park. Community members, primarily youth learn computer skills, as well as accessing the internet and community websites in the local languages. CTPH has created web content on these websites about the importance of being healthy and hygienic to prevent disease transmission between people and gorillas, which in turn promotes sustainable ecotourism and livelihoods. When people learn how to use the computer and access the internet, it opens up their world, and they can communicate with the tourists they meet, other stakeholders in the tourism, conservation and development sectors; and also carry out e-commerce such as sending photos of the crafts they are selling to potential buyers worldwide as well as making bookings through the internet for tourists to stay at their accommodation.

Mongabay: The center has courses in Computer Studies. How important is education to the local people?

CTPH brochure in local language and English. Photo courtesy of CTPH. |

Gladys Kalema-Zikusoka: Education is very important to the local people, because it is the main way to break the poverty cycle. With computer skills the local people can get jobs, and be in a better position to seek support for their communities through the internet. CTPH has just started a distance learning program between schools in Uganda and schools in New York State to promote cross cultural learning of the social and natural sciences.

Mongabay: What advice would you give a local student interested in pursuing conservation?

Gladys Kalema-Zikusoka: The advice I would give to a local student interested in pursuing conservation is to volunteer with a conservation organization, such as a government body like Uganda Wildlife Authority, conservation NGOs like CTPH, local Community Based Organizations, small and medium enterprises and tour companies working around protected areas. This will enable them to gain exposure into all aspects of wildlife conservation, including biodiversity protection, research, veterinary medicine, public health, law enforcement, community conservation, tourism, marketing, public relations and business development.

Mongabay: What are the greatest challenges of your work?

Gladys Kalema-Zikusoka: The greatest challenges of my work are both internal and external. The internal challenges include not having enough resources to do the work that we feel needs to be done; this includes funds, people and equipment. So I end up having to do alot of multitasking which includes fundraising, making sure that the core activities are ongoing, in other words that our field programs are running, as well as the supporting finance and administration. We also find that there is a great need to carry out marketing and public relations yet do not have enough resources and this is an area that donors don’t like to fund.

The external challenges include convincing people that integrating wildlife conservation and public health can create common benefits for both people and animals. Sometimes when we go to human health donors they say that we are animal people or when we ask conservation donors for funds to support community public health they say that this is public health not conservation. However we have made great progress in explaining this approach and received support from donors who see CTPH as a cutting edge approach to promoting wildlife conservation and integrated conservation and development initiatives (ICDs). This approach is also because public health is one of the most important indicators of poverty in the developing world.

Mongabay: You recently won the Whitley Gold Award for grassroots nature conservation. Can you tell us about this award and what does it mean for CTPH?

Mountain gorilla in Bwindi, Uganda. Photo by: Rhett A. Butler. |

Gladys Kalema-Zikusoka: Wining the Whitley Gold Award for grassroots nature conservation commonly known as the “Green Oscars” is a very great honour for CTPH, our partners and supporters. We were particularly honoured to hear the words of Edward Whitley who said that the aim of the Whitley Awards is to find and support conservation scientists whose vision, passion, determination and qualities of leadership mean they are achieving inspirational results in conservation, and that CTPH demonstrates all this and more. The photograph of HRH, Princess Anne presenting the award, at a ceremony at the Royal Geographical Society in London, generated alot of interest and recognition from all sectors of society in Uganda and from the international community. It also resulted in many interviews with the media to promote the importance of gorilla conservation and how public health is providing a tangible benefit for communities surrounding the park. This is particularly significant this year because it is the International Year of the Gorilla, and further highlights our efforts at CTPH to protect a species that has become a symbol of what conservation means and offers its human neighbours access to useful tourism income, but yet is vulnerable to human diseases because we share 98% of DNA.

The Whitley Gold Award also generated much needed funds to run the operations of CTPH. The funds will be used to measure the conservation impact of CTPH’s work in Bwindi Impenetrable National Park by documenting improvement of hygiene indicators of community members who regularly interface with gorillas and resultant effect on the gorilla health status.

Mongabay: What can people do to help CTPH?

Gladys Kalema-Zikusoka: People can help CTPH by spreading the word about CTPH and the urgent public and animal health needs that we address; joining our membership program that is soon to be launched, adopting a gorilla or gorilla group where you will receive regularly updates on the gorillas or group that you adopted; providing grant funding for one of our new initiatives or sustaining the ongoing initiatives; making an individual gift to support our work, visiting us on a working holiday with CTPH where you will get to work at our Gorilla Research Clinic and with our community public health and telecentre team. If you choose to stay at the CTPH Silverback Gorilla Camp in Bwindi, where all fees for meals and lodging support the work of CTPH, you will get a tour of our Gorilla Clinic, hear a presentation on health threats to the endangered Mountain Gorillas, go gorilla tracking, bird watching and hiking in the forest.

Conservation through Public Health

Kalema-Zikusoka will be presenting at the upcoming Wildlife Conservation Network Expo in San Francisco on October 3rd.

Related articles

Uganda abandons rainforest logging for palm oil

(05/27/2007) The Ugandan government abandoned plans to log thousands of hectares of rainforest on Bugala island in Lake Victoria for a palm oil plantation, Reuters reported Saturday.

Rare mountain gorillas in Uganda on the increase

(04/20/2007) High endangered mountain gorillas in Uganda are increasing, reports a new census by the Uganda Wildlife Authority, the Wildlife conservation Society, the Max Planck Institute of Anthropology and other groups. The population of gorillas in Bwindi Impenetrable National Park has increased from 320 in 2002 to 340 today. A 1997 study found 300 gorillas, indicating that the park population has increased by 20 percent over the past decade. Aggressive conservation measures have been the key say researchers.