|

|

Sarawak, land of mystery, legend, and remote upriver tribes. Paradise of lush rainforest and colossal bat-filled caves. Home to unique and bizarre wildlife including flying lemurs, bearcats, orang-utans and rat-eating plants. Center of heavy industry and powerhouse of Southeast Asia.

Come again? This jarring image could be the future of Sarawak, a Malaysian state on the island of Borneo, should government plans for a complex of massive hydroelectric dams comes to fruition.

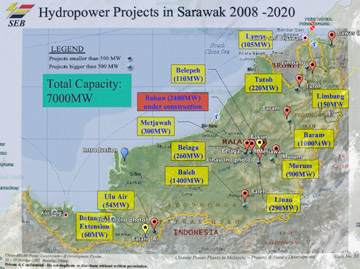

The plan, which calls for a network of 12 hydroelectric dams to be built across Sarawak’s rainforests by 2020, is proceeding despite strong opposition from Sarawak’s citizens, environmental groups, and indigenous human rights organizations. By 2037, as many as 51 dams could be constructed.

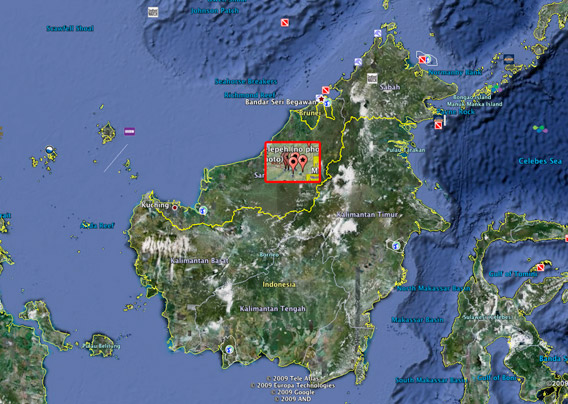

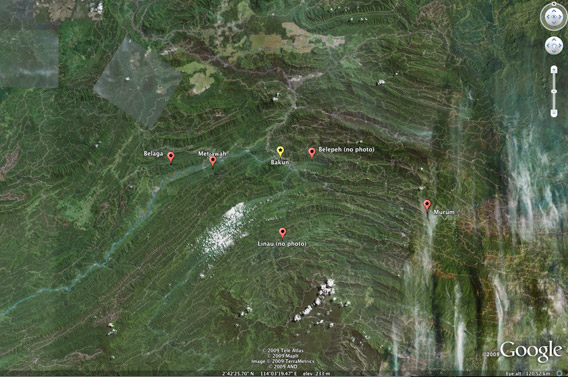

Proposed dams in Sarawak. For details see David Tryse’s Flooding Borneo’s rainforest: Sarawak’s confidential dam plans 2008-2020 [Google Earth KMZ file] |

The plans came to public attention in 2008 when a confidential document was accidentally published on a Chinese website. The project will create one of the largest hydropower complexes outside China and will be developed by the China Three Gorges Project Corporation, the state-owned company responsible for the dam of the same name.

The 12 initial dams will have the capacity to produce 7,000MW—a 600% increase in Sarawak’s electricity production. The state already produces 20 percent more power than it uses.

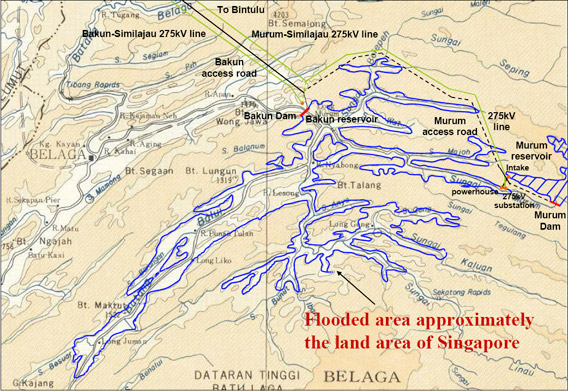

The plans have attracted fierce criticism because of the catastrophic destruction they are expected to cause. One dam has already displaced 10,000 native people and will flood an area the size of Singapore. Several more communities could be engulfed, displacing at least 1,000 more people. Parts of Mulu National Park, home to the world’s largest cave, could be submerged, potentially threatening its UNESCO World Heritage Site status.

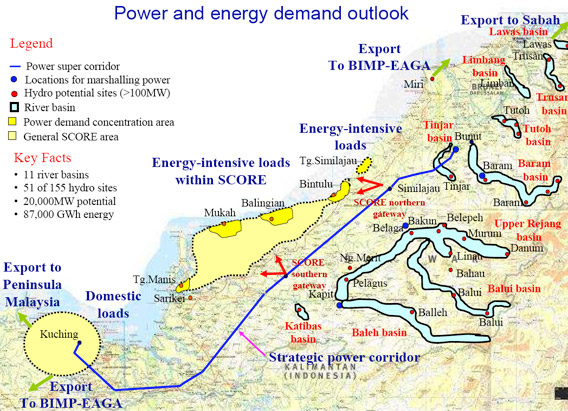

The main reason for the dams’ construction cited by the Malaysian government is the development of industry in Sarawak. The Sarawak Corridor Of Renewable Energy (SCORE), a potential 320km economic development region, promises to bring employment opportunities and infrastructure development for the state, which suffers from below-average levels of employment and income. The dams will provide cheap renewable electricity to the power-intensive industries it is hoped the corridor will attract.

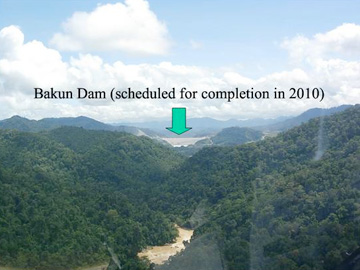

Bakun dam in Sarawak. |

But such high-energy industries will bring more than potential profit. Environmental groups warn the influx of smelters and refiners will generate mountains of waste and pollution. Local NGOs further question how many of the promised jobs will go to displaced indigenous people.

The dams will also apparently supply electricity to peninsular Malaysia via a 700km undersea cable. The cable project was finally approved by the Malaysian government in April this year after being repeatedly dropped and reinstated.

Dr Kua Kia Soong, director of the Malaysian human rights organization SUARAM, claimed in a statement last year that power stations on the peninsula were not working at full capacity, that the state electricity provider, TNB, was selling off property, and that the electricity industry was deep in debt, calling into question whether such a huge, expensive and disruptive project is justified.

But Energy Minister Peter Chin Fah Kui maintains that, “in the long term, it will be more economical and viable to transmit power from Bakun [dam] to peninsular Malaysia even though the undersea cable project will be very costly.”

Environmentalists have voiced concerns over the safety of the submarine cable, as it will pass through a region prone to earthquakes.

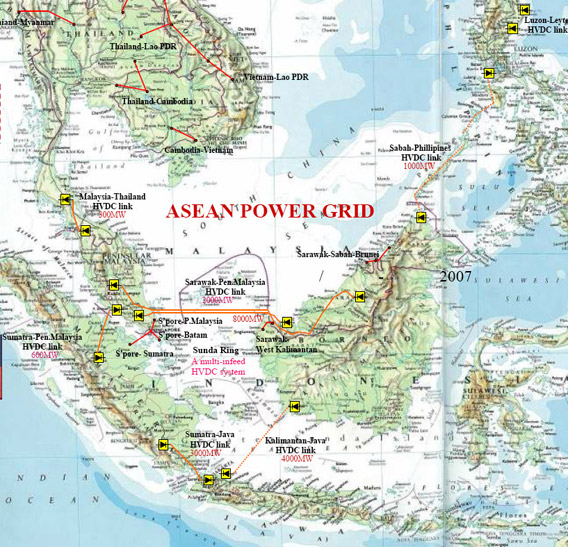

Less well known are the state’s intentions to export vast amounts of electricity. Sarawak aims to play a major role in meeting the increasing power supply demands of countries across Southeast Asia including Brunei, Indonesia, and the Philippines. Sarawak is effectively set to become the powerhouse of Southeast Asia.

This is part of the ASEAN Interconnection Master Plan, which proposes to connect the power systems of a number of Southeast Asian nations for “mutual benefits.”

But these ambitious plans are not explained to indigenous people when they are uprooted from lands they have inhabited for generations. They are told of the industry that will come to Sarawak, bringing with it jobs and development for the people; not that they must give up their homes to supply power to Malaysia’s neighbors. But they have little say in the matter.

Power grid in ASEAN region. Image courtesy of the Energy Commission of Malaysia. |

Environmentalists have been fighting against Bakun dam—the first and largest of the dams—since its conception in the 1980s. So when the government’s plans for a further 12 dams were leaked, environmental and indigenous peoples’ organizations were up in arms. Shortly after the revelation, a coalition of Malaysian NGOs demanded the government “formulate a comprehensive energy policy.” The plans, said Gurmit Singh, spokesperson and chairman of the Centre for Environment, Technology, and Development, Malaysia (CETDEM), “illustrate an energy planning strategy that is supply driven and inconsistent with the principles of sustainable development.”

While the project’s supporters say that dams are a source of “clean” energy, a spate of scientific studies has shown that large dams produce large-scale carbon dioxide and methane emissions from the rotting of vegetation in flooded forests. Furthermore, dams severely affect river hydrology, bringing unpredictable implications for entire river catchments.

Critics argue that the impact on Sarawak’s environment and indigenous communities will be devastating, involving massive flooding of pristine forested areas, displacement of thousands of indigenous people, fragmentation of forests affecting endangered and endemic plants and wildlife, and extensive damage to rich biodiversity in river headwaters.

|

Since the plans became public, there has been a continual outcry in the Malaysian and International press, but protestors appear to be powerless. Some are beginning to feel there may be no hope.

“Everything that needs to be said has been said, and by the very people affected by these decisions, to no avail,” said a council member of the Malaysian Nature Society (MNS), who wished to remain anonymous.

But there are glimmers of hope. A recent community forum held by SUHAKAM, the Human Rights Commission of Malaysia, saw some apparent changes in attitude from government representatives, a hopeful sign that they have started to listen.

The official outcomes of the forum are yet to be released, but SUHAKAM Commissioner Dr. Mohammad Hirman Ritom Abdullah told Mongabay that the government does now seem to be responding to the concerns. “I personally felt there was a change in the attitude of the state government,” Dr. Hirman said. “In the past they have been quite protective over what they are going to do, not engaging.” He added that there are some positive things happening in the state in terms of planning.

But actions speak louder than words, and with so many broken promises littering the history of Sarawak’s hydroelectric plans, people’s trust is fragile.

The forum was held to discuss the “concerns and aspirations of affected/concerned parties for the Government to consider before implementing future dams,” following a Murum dam site visit by SUHAKAM commissioners and officers to observe the impact on the environment.

Murum is one of the “big four” dams in the projects development. The others are Bakun, Baram, and Balleh. These four will be the first to be constructed.

With an expected output of 2,400MW, the Bakun dam is the largest and first dam of the project, acting as a flagship—for all the wrong reasons, its opponents feel. Since its proposal in 1980, it has been plagued with cost overruns and delays: plans for its construction have twice been shelved for financial reasons. The numerous failures of Bakun have been widely publicized, and are often cited as a prime example of the Malaysian government’s poor planning and general disregard for its people and environment.

Area to be flooded by Bakun. Image courtesy of the Energy Commission of Malaysia. |

The constant abandonment and reinstatement of projects such as Bakun and the undersea cable suggest poor planning and raises questions over the Malaysian government’s ability to finance such a huge project, the critics say.

Bakun dam will flood 700 square kilometres of rainforest. Environmental groups recently revealed this area is being cleared using fire, violating Malaysian legislation against open burning. Smoke from the burning forest remnants is thickening the blanket of polluting haze that already hangs over the region.

The amount of power produced by Bakun alone is double the amount currently used by the whole of Sarawak. In order to use up the extra energy, Sarawak-based infrastructure firm Cahaya Mata Sarawak (CMS) and Anglo-Australian mining giant Rio Tinto plan to build a “world class” aluminum smelter nearby. Aluminum smelting is a voracious consumer of power and the plant is expected to use half of the electricity produced by Bakun.

But CMS has been accused of taking advantage of political power as well as hydroelectric power from Bakun.

The company is already a major beneficiary of the dams project. As well as the enormous aluminum smelter, the firm is producing construction materials for Bakun dam on a large scale. Perhaps it is coincidence that the company is owned by the family of Sarawak’s long-standing chief minister, but opponents of the plans point to corruption and “crony capitalism.”

Chief Minister Abdul Taib Mahmud also acts as Sarawak’s Planning Minister and Finance Minister, and has interests in many of the state’s largest companies. He has been behind much of the development of Sarawak over the last 30 years, but his family’s extensive commercial interests in many of the projects he approves has raised questions about conflicts of interest. It has even been claimed that he owns Sarawak Forestry.

According to Al Jazeera, the contract for the smelter was awarded without open bidding, in direct violation of Malaysian law. In an interview broadcast on the news channel in March this year, Sarawak’s Land Minister James Masing strongly denied the claim, maintaining that the process was transparent.

“This [aluminum smelting] project . . . has the potential to generate significant social and economic benefits for Malaysia and local communities in Sarawak,” said Oscar Groeneveld, Rio Tinto Aluminum’s chief executive, adding that CMS and Rio Tinto Aluminum are “committed to developing the project to world class environmental and community standards.”

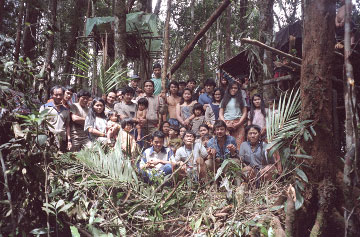

In March 2006, Interhill, a Malaysian logging company, cleared land around Ba Abang, a Penan village in the Middle Baram region. Photo by the Bruno Manser Fund |

These “world class environmental standards” have been brought into doubt recently. “Recommendations we have made for the Rio Tinto aluminum smelter were not adhered to,” reported a MNS council member, going on to describe how land had been cleared to within 10m of the Similajau River. The advised limit was 50m. The boundaries of Similajau National Park, home to five species of dolphin including the critically endangered Irrawaddy dolphin, begin on the opposite river bank.

Dr. Hirman says that at the SUHAKAM community forum, the government’s environmental adviser and state planning unit secretary were “talking in terms of complying with environmental principles.”

But was that talk backed by steps toward compliance? What about the Rio Tinto case? Dr. Hirman said, “The Environmental Board themselves are not happy with the contractors. It is important how people implement their policies; it is the monitoring that needs to be strengthened”

There have been other reports of environmental recommendations being ignored in the area. “They have already cleared the land although the DEIA [Detailed Environmental Impact Assessment] for Tokuyama Polypropylene Plant is not even finished—they are more interested in removing the logs than anything else,” said another MNS council member.

Such disregard for environmental guidelines raises the question of the purpose of Environmental Impact Assessments (EIAs). Are they merely an empty gesture to pacify environmentalists with promises of environmental protection until it is too late and the damage is done? The problem lies in Sarawak’s legislation. “According to the law that we have here, even if the EIA is bad they can proceed with the dam” said Raymond Abin of Borneo Resources Institute Sarawak (BRIMAS).

Belaga dam site  Murum dam site  Metajawah dam site. Images courtesy of the Sarawak Energy Berhad with credit to the Bruno Manser Fund. |

In response to environmentalists’ concerns about the legislation surrounding EIAs, former Environment and Public Health Minister Datuk Michael Manyin said that EIAs are mandatory and have to be submitted to the Natural Resources and Environment Board (NREB) for review and approval. “The NREB imposes stringent conditions which the project proponent has to comply with to ensure that the environment is properly managed and protected during the project implementation and operation,” he said, adding that public participation had always been incorporated into the EIA process.

Manyin added that any decision made by the state to develop the dams would be done “with much due consideration for the best interests of the people of Sarawak.”

Bakun alone has already displaced 10,000 indigenous people of Sarawak, at a cost of over $248 million. Some people were told they must pay for their new houses in the resettlement area, even though many have still not received the compensation they were promised over ten years ago.

Native community rights were violated, and the social atrophy the communities have suffered continues unaddressed by the government.

Members of the Penan community in particular have struggled with the new way of life. As a semi-nomadic tribe of hunter-gatherers, a settled lifestyle of farming and monetary trade was difficult to adapt to. “People are still having problems,’ says Dr Hirman of SUHAKAM. “[Problems such as] access to land, and some of the land that was given not being arable. There have been cases where electricity and water was cut off because they did not pay the bills; they’re just not ready for a cash-oriented lifestyle.”

“These are the kind of people you need to provide infrastructure for while at the same time [you] provide access to their original environment where they can still go the jungle and supplement whatever they need. This is something that is not done.”

A further 1,000 people are due to be displaced by Murum dam, a 920MW dam due for completion in 2013. Work began in May this year.

Among those to be displaced are the Penan community of Long Jaik. The people here are defiant, saying that they will stay despite the government’s plans to relocate them.

Power and energy demand outlook for Sabah. Image courtesy of the Energy Commission of Malaysia. |

According to Matu, a member of the Long Jaik community, his people have been told that they are not developed because they are dispersed, that they must be gathered into one place to be developed. “The government told us they want to build the Murum dam to enable the Penan to develop in terms of education. They said, ‘We’ll give you a school and a clinic.’ I told them: ‘If you want to develop the Penan like me, develop me here in Long Jaik. Bring a school and a clinic here to me in Long Jaik.”’

The people of this community are concerned they will not be sufficiently compensated after seeing the plight of those relocated to make way for the Bakun dam. “When I look at the people who have moved to Sungai Asap—especially the Penan—they live a very difficult life,” Matu said in an interview with Survival International, an organization that works to support tribal people worldwide. “If we move, they will give us only one hectare per family. Here, we easily have ten.”

“My ancestors… have struggled to protect this area for us. It has been used by Penan for 12 generations,” Matu continued. “I feel it’s my responsibility to stay and protect this land for generations to come. If we move from here and forget our ancestors, who will own, use and take care of this land? The Chinese will use it. They’re not the owners, but they will keep it for themselves and we won’t be able to hunt or fish here anymore. We are the rightful owners, but we won’t be able to access the land.”

Dr. Hirman noted, “Until this whole land issue [Native Customary Rights] is cleared up, it is going to impact on whatever mitigation factors the authorities are going to carry out.”

The EIA for the third dam, Baram, has now begun. But according to Raymond Abin of BRIMAS, the local community has not been consulted; the first they knew of the proposed dam was when consultants arrived to conduct the study.

Baram dam site  Baleh (Balleh) dam site. Images courtesy of the Sarawak Energy Berhad with credit to the Bruno Manser Fund. |

And they are apparently being told selective truths about how the generated power will be used. Abin observes, “They are saying that we need to have more industry coming to Sarawak; that’s why we need all these dams. They are talking about employment opportunities for people.” But they are not telling people about their plans to export power to other countries.

“The study is not transparent without the involvement of the people,” Abin notes. ‘It is always the Chief Minister having the upper hand.”

The people affected by the Baram dam are concerned for their future. “We foresee there will be a determined opposition to Baram in the near future,” Abin says. ‘Looking at how they dealt with Bakun, I think they learnt from that. Despite the public opposition to it they just continued. But we will see; every case is different.”

A proposed national park, and an internationally recognized “Important Bird Area” of highland bird species with restricted ranges, is the site of the fourth dam in line, Balleh. According to the Malaysian Nature Society, the site is geologically unique with spectacular volcanic cliffs. “With its rich geological heritage, the Balleh site is invaluable to mankind,” the society said in a statement voicing concern about the dam. Work has not yet begun at Balleh, but it is due for completion in 2017.

The Malaysian government sees economic value in Sarawak’s rivers, from their capacity for power generation. But there is a different kind of value in the state’s natural riches, besides their inherent biological value. Treatments for HIV and cancer lie in Sarawak’s forests, some of which are already in the final stage of development as pharmaceutical drugs. It is unknown how many more potential cures are waiting to be discovered; many may be lost before they are found if the forest continues to be destroyed.

Emerging initiatives such as REDD (Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation) offer alternatives to clearing of forests for “economic development” projects such as plantations and hydroelectric dams.

Such schemes are increasingly seen as a viable method of protecting forests from destruction. Under the REDD program, economic incentives are offered to countries for preserving forest cover, and in doing so climate change from forest clearance is mitigated, local communities are supported, and biodiversity is protected.

The Sarawak dams will cause more than just loss of forests, but the point is that there are ways of generating financial rewards from keeping ecosystems intact. Scientists and politicians are increasingly looking to such models of financial reward for protection of ecosystems, which include ecosystem service payments, bio-banking, and carbon payments, as an intelligent answer to the complex problems of deforestation and climate change.

Images courtesy of Google Earth. |

In addressing such complex problems, the schemes face many challenges. Carefully constructed financial structures, clear definitions, and effective regulation and monitoring are needed to ensure their success. Assessments by independent think tanks such as CIFOR (Center for International Forestry Research) have shown that if such considerations are incorporated, schemes such as REDD could be a success.

Ecotourism has huge potential as a revenue generator and, if properly managed, protects biodiversity rather than destroys it. Madagascar is a leading example of how profitable ecotourism can be for a country; the industry represents a significant proportion of the country’s GDP. Conservation in Madagascar is largely funded by ecotourism, thanks to a series of initiatives established by recently ousted president Marc Ravalomanana.

But, for now at least, it seems that the Malaysian government will plow on with its dams, regardless of the increasingly desperate pleas of its people and the loss of its greatest natural assets.

Will Sarawak retain at least part of its storied past and its paradisal rainforests with their abundance of plant and animal life? Or will those all vanish in the march of industry? That’s the balancing act ahead for this once remote and exotic land.

See David Tryse’s Flooding Borneo’s rainforest: Sarawak’s confidential dam plans 2008-2020 [Google Earth KMZ file] for a graphical/spatial representation of the dams.

The author would like to thank Raymond Abin (BRIMAS), Daniel Austin, William Bridges, Rhett Butler, Dr. Mohammad Hirman Ritom Abdullah (SUHAKAM) and Miriam Ross (Survival International) for their assistance with this article.