First in a series of interviews with participants at the 2009 Association of Tropical Biology and Conservation (ATBC) conference.

Sometimes we lose sight of the forest by staring at the trees. When this happens we need something jarring and eloquent to pull us back to view the big picture again.

This is what tropical ecologist Jaboury Ghazoul provided during a talk at the Association of Tropical Biology and Conservation (ATBC) meeting this summer in Marburg, Germany. Throwing out a dazzling array of big ideas and even bigger questions—incorporating natural history, biodiversity, morality, philosophy, and art—the enthusiastic Ghazoul left his audience in a state of wonder.

Mongabay couldn’t help but catch up with Ghazoul and discuss the questions raised in his talk: our crisis generation; why biodiversity matters; the connection between economy and nature; the ‘inherent’ value of life; building a conservation ethic; and the moral implications of sharing—rather than ruling—the plant.

Jaboury Ghazoul. |

Like his talk in Marburg, Ghazoul leads us out from the trees to see the whole forest.

PERSONAL

Mongabay: What is your background?

Jaboury Ghazoul: I am lucky in having had the privilege to spend the first 13 years of my life growing up in two countries, Iraq and the UK, both of which shaped my interests, experiences and cultural perspectives. These experiences were enhanced further through the eight years I spent in Scotland as a university student, during which time I had inspirational friends, teachers and landscapes. A career in marine biology was derailed by an opportunity to work in Vietnam for a year which led me, via another three years in Thailand, into tropical forest ecology. I have since enjoyed studying tropical forest ecology and conservation in many Southeast Asian countries, but also in India, southern Africa and Latin America. After an eight year stint at Imperial College London I now find myself in Zurich, still enjoying the challenges of tropical forest ecology and conservation—though if someone were to offer me a job in marine ecology, my first love, I would be seriously tempted!

Mongabay: What is your primary area of study?

Jaboury Ghazoul: We mainly study the viability of plant populations in tropical but human-dominated landscapes. In shaping the landscape for our own immediate needs we have altered ecological processes, species compositions and habitat patterns. There are, of course, many implications

Mongabay: You have called this generation the ‘crisis generation’. What do you mean by that term?

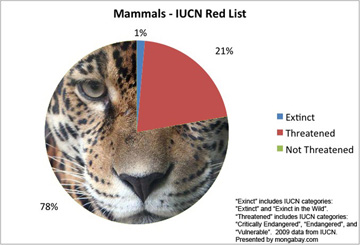

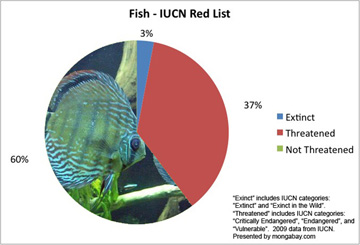

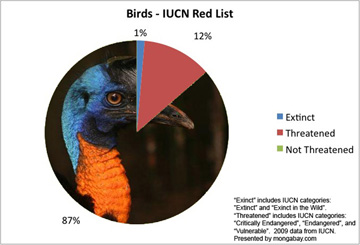

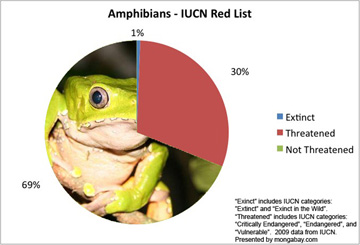

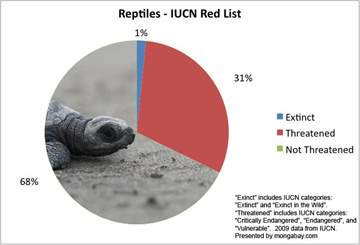

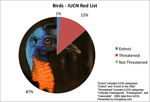

Percentage of species extinct and listed as threatened by extinction according to the IUCN. However, the IUCN lacks data on many species and has little information on the threatened status of plants, invertebrates, and insects. |

Jaboury Ghazoul: Every generation has its crises. In the past these were often pestilence and famine, sometimes on catastrophic scales. We also happen to have crises that are global in extent, but what’s more, they are truly novel. Unlike diseases and famines, rapid climate change is not something that we have had to deal at global scales. We have also become exceedingly good at publicizing our crises. Not a day goes past when I do not read something about energy shortages, water conflicts, biodiversity loss, climate change, pandemic diseases, food security.

BIODIVERSITY AND ECONOMY

Mongabay: To the non-biologist, why does biodiversity matter?

Jaboury Ghazoul: Two reasons. One, the variety of life underpins life support and economic systems in more ways than can be conceived—we are still discovering the full range of interactions by which we benefit from a rich biodiversity. Two, our natural heritage, be it local or global, enriches our personal and societal cultures. A failure to appreciate this constrains our mindset and impoverishes humanity.

Mongabay: You wrote an op-ed in Science this January pondering what would happen if America’s stimulus package actually went to saving the world’s biodiversity. Do you think 789 billion dollars would be enough?

Jaboury Ghazoul: Who can tell what is enough? Certainly managing the world’s biodiversity does not require a one-off cash injection, but rather an ongoing commitment in perpetuity. A cash injection of 789 billion dollars will, after all, be exhausted at some stage, and interpreted in this way it is clearly not enough. My guess though, is that a lot less would go a very long way towards making a necessary and immediate change for the better. I have estimated that current spending on all conservation related activities is around 14 billion dollars per year, globally. Despite this ecosystems continue to be degraded and species lost, and despite our best efforts of restoration we will never be able to fully recover lost natural capital. So to make the biggest difference we need to act now while we still have what we have, and in such circumstances a few hundred billion would help.

Mongabay: How does society’s spending habitat’s reflect our priorities? What do you think those priorities are today?

Jaboury Ghazoul: Since writing the Science article it has become clear that 789 billion dollars was actually only the first installment of a stimulus package that is now several times that amount—principally to rescue a corrupt financial system. Regretfully, this does reflect societies’ priorities, but does not reflect well on society. I am no economist, but I expect there is an element of truth in my suggestion that investment in other societal values, which should be elevated to priorities, would have wider economic benefits. I refer the need for far more investment in activities and economies that work with the environment rather than against it. Climate change, for example, is potentially catastrophic for nature and humans, but in responding to its challenges it presents very many opportunities for new economic growth—if only we could be brave enough to make the appropriate policy and investment decisions. In investing in response to climate change and acting to reverse biodiversity loss, we are also working towards current societal priorities. Top of the list are, perhaps, inexpensive and continuously available energy, good health and education systems, plentiful and rich food, and peaceful and stable societies. If one cares to investigate how to deliver these societal objectives they quickly discover that underpinning all these priorities is a well functioning and diverse environment.

Purple-striped jellyfish Chrysaira colorata at the Monterey Bay Aquarium. Photo by: Rhett A. Butler. |

Mongabay: Why do you think biodiversity is very low—or often not even mentioned—on many media and government’s list of global problems, i.e. economy, terrorism, fossil fuels, water shortage, food crisis, climate change?

Jaboury Ghazoul: There are many political, social and economic reasons, but in short, governments respond to meet the immediate, often perceived, needs of their people. To a large extent it is the economy that underlies peoples’ well being, and this is what people respond to, but quality of life consists of far more than a strong economy. Prosperity has been built on the exploitation and control of nature, and while this has worked for much of human history, with occasional hiccups, the accumulated impact is now beginning to tell. The problem is that people and governments remain grounded in the belief that we can address current problems within the existing paradigm of control. There is societal inertia in adjusting to new realities, particularly when the new realities require us to grapple with the complexity of our interactions with biodiversity and the wider environment. The solutions are not immediately obvious and often lack direct benefit—and the benefits of biodiversity conservation are indeed diffuse. So we have a global tragedy of the commons scenario that limits foresight. The same applied, until recently, to climate change, and it is only now as we begin to feel the impact of climate change directly—heat waves in Europe, fires in California and Greece, coastal damage and inundation in the Netherlands and New Orleans, failed monsoons in India—do we respond to our immediate need.

Mongabay: Do you think apart of the problem is due to scientist’s difficulty in communicating to non-scientists why biodiversity matters?

Life rising: swarms of lake flies in a garden near Lake Victoria, Uganda. Photo by: Rhett A. Butler. |

Jaboury Ghazoul: To some extent, yes, although this is a simplification. I don’t think that scientists are any better or any worse at communication than the next person. Scientists perhaps have an even harder time of it as they often deal with complex scenarios which they do not fully understand, but the same could be said for other sectors of society. Communication is more than just conveying information, it is also about receiving it. Scientists may not be very good at conveying information, but it is equally valid that much of society is simply not well attuned to receiving it. In our modern and largely urban-centered societies people have become dissociated from biodiversity in a direct sense, and as a result find it more difficult to understand their dependencies on it.

Mongabay: There has been a lot of discussion recently about integrating the economy with environmental services, such as paying countries to keep their tropical forest’s intact as carbon sinks. Do you think this is the right approach? Is it the only?

Jaboury Ghazoul: It is one approach, but is not sufficient in itself. The danger is when we are able to engineer solutions to constraints that bypass the need for environmental services. For example, if we are able to develop a network of effective Carbon Capture and Storage technologies then we would reduce the need for natural carbon sinks. Perhaps natural carbon sinks will continue to be an important element of our carbon capture portfolio as we transition to a low carbon economy, but once that transition is complete, as I believe it will be within 50 years, then what value for forests? We need to invest much more in raising awareness of the inherent value of forests, and biodiversity in general, particularly through its contribution to our cultural and psychological well being. Persuading people that biodiversity has inherent value is unlikely to work, but by working to enthuse people with natures’ wonders then we will continue the transition to a society that values nature for far more than the simple economic benefits that it provides.

TOWARDS A CONSERVATION ETHIC

Mongabay: Why is it important to instill individuals with a ‘conservation ethic’? How do we do it?

Jaboury Ghazoul: I do not believe that economic arguments for nature conservation are sufficient to maintain good quality ecosystems that support a rich biodiversity. We must change societal awareness to recognise the fascinating and wonderful natural heritage that we have been bequeathed, but which we are losing. Once we as a society recognize this inherent value of biodiversity, and are imbued with this conservation ethic, then societal priorities and government policies will respond accordingly. We can only do this by ensuring people have more direct contact with nature, coupled with an education system (both formal and informal) that conveys not just knowledge but also a sense of wonder by which direct experiences can be married with informed enthusiasm.

Jaboury Ghazoul’s children collecting insects. |

Mongabay: Why is it important for children to have experiences in nature?

Jaboury Ghazoul: Children have immense powers of imagination and creativity, and a child’s natural enthusiasm is easily sparked by immersion in nature. Such experiences shape a person’s character and mentality, and while most kids will subsequently discover and pursue new pathways they are unlikely to forget formative encounters with the natural world. In seeking to raise societal awareness of the intrinsic value and wonder of nature it therefore makes sense to engage the children—not only are they most receptive, but it is they after all who will within two decades be the practitioners, policy makers and voters. Besides, there is always something new to see in nature, wherein the coupling of a child’s creativity and an imaginative guardian will be sure to reward both.

Mongabay: With more and more people living in urban environments (and rarely, if ever, spending time in an intact natural ecosystem), how do you suggest city-dwellers connect with nature?

Jaboury Ghazoul: Nature is all around us—you just have to look with open eyes. I now live in a city, albeit a small one, and have no difficulty engaging with nature, be it with the spiders in our bath, the moths in our garden, or the detritus in the gutter. Gardens and parks are full of species interacting with each other, and even cemeteries are full of life. A small vial of pond water from the local park will reveal a fantastic array of organisms under a simple microscope. Try growing fruit and vegetables in a corner of your garden or allotment, and enjoy the variety of insects, weeds and fungi that you attract. Plant flowers on the balcony of your apartment and you will get far more than you bargained for. And if you still want more, then visit the countryside, by bike or on foot, armed with a flower guide, an insect guide and a magnifying glass and prepare to be fascinated. Better still, spend a day at a rockpool.

Ants in Laos. Photo by: Rhett A. Butler. |

Mongabay: You say that scientists must ‘understand society from multiple perspectives’. Can you explain this? How would this new understanding make scientists better communicators with non-scientists (not to mention more well-rounded)?

Jaboury Ghazoul: Conservation is a matter of societal choice. A good conservationist is one who appreciates this and therefore seeks to understand how different people from diverse backgrounds and social situations feel and think, not just with regards to conservation, but with respect to their livelihoods, desires and values. Once we truly begin to understand what values and priorities different elements of society have, then we can begin to propose strategies for conservation that are likely to be heard, understood and appreciated.

Mongabay: What role do you think religion could play in instilling society with a ‘conservation ethic’?

Jaboury Ghazoul: We all have our own moral code, sometimes shaped by a chosen religion, and sometimes derived from multiple experiences and teachings. Regardless of its source, what defines human morality, and what differentiates us from other animals, is an ability to consider what we ought to do—in other words what a morally correct course of action should be. This presupposes a respect for others, and our morality, from wherever it may be derived, is founded on a common respect for the rights of others. Thus religion could certainly play a major role in encouraging people to consider their own conservation responsibilities, but equally there is a role for art, literature and philosophy as mechanisms through which we can be encouraged to think more deeply about our relationship with the nature around us.

Nature in urban environments: an oak tree at least 600 years old near the urban populations of Sheffield and Manchester. Photo by: Jaboury Ghazoul. |

Mongabay: Do you think conservation is a moral imperative? If so why?

Jaboury Ghazoul: I do, but it is not easy to explain why. It is something that has been imbued within me, either from birth, or gained through the encounters I have had, the books I have read, the people I have conversed with and the nature I have wallowed in. We ought to conserve biodiversity, not because it has economic value, but because recognizing our responsibility to the world within which we live, as much as to the society within which we prosper, is what makes us human.

Mongabay: Do species have a moral right to exist even if they serve no function to humanity?

Jaboury Ghazoul: In view of what I have already said, I would argue yes, but nevertheless I am mightily pleased that smallpox has been eradicated. I absolve myself of guilt by accepting that viruses are not really species.

Mongabay: How much hope do you have for the world’s biodiversity in the long-term?

Jaboury Ghazoul: I have a lot of hope that vast majority of the world’s species will still be with us at the end of this century, although I fear that many will persist only in a few forgotten corners. But I am also hopeful that the current alarming trends in environmental degradation and forest loss will slow and eventually reverse, allowing degraded land to return to nature. I envisage future landscape mosaics to comprise a mixture of managed and semi-natural habitats, which collectively will support much biodiversity. And if we have learned anything in the last few decades of ecological research, it is that nature is much more resilient to change than we gave her credit for.

Mongabay: How much hope do you have for humanity?

Jaboury Ghazoul: Ah, now that’s another story.

Related articles

Investing in conservation could save global economy trillions of dollars annually

(09/03/2009) By investing billions in conserving natural areas now, governments could save trillions every year in ecosystem services, such as natural carbon sinks to fight climate change, according to a European report The Economics of Ecosystems and Biodiversity (TEEB).

(08/17/2009) Founded in 2004 by legendary conservationist Richard Leakey, WildlifeDirect is an innovative member of the conservation community. WildlifeDirect is really a meta-organization: it gathers together hundreds of conservation initiatives who blog regularly about the trials and joys of practicing on-the-ground conservation. From stories of gorillas reintroduced in the wild to tracking elephants in the Okavango Delta to saving sea turtles in Sumatra, WildlifeDirect provides the unique experience of actually hearing directly from scientists and conservationists worldwide.

REDD shouldn’t neglect biodiversity say scientists

(07/30/2009) Schemes to mitigate climate change by protecting tropical forests must take into account biodiversity conservation, said two leading scientific organizations at the conclusion of a four day meeting in Marburg, Germany.

869 species extinct, 17,000 threatened with extinction

(07/02/2009) Nearly 17,000 plant and animal species are known to be threatened with extinction, while more than 800 have disappeared over the past 500 years, reports the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN). While these numbers are substantial, they are likely “gross” underestimates since only 2.7 percent of 1.8 million described species have been assessed. The IUCN report warns that governments will miss their 2010 target for reducing biodiversity loss.