Sixth in a series of interviews with participants at the 2009 Association of Tropical Biology and Conservation (ATBC) conference.

With the world facing a variety of crises: climate change, food shortages, extreme poverty, and biodiversity loss, researchers are looking at ways to address more than one issue at once by revolutionizing sectors of society. One of the ideas is a transformation of agricultural practices from intensive chemical-dependent crops to mixing agriculture and forest, while relying on organic methods. The latter is known as agroforestry or land sharing—balancing the crop yields with biodiversity. Shonil Bhagwat, Director of MSc in Biodiversity, Conservation and Management at the School of Geography and the Environment, Oxford, believes this philosophy could help the world tackle some of its biggest problems.

Bhagwat first became interested in agroforestry when he studied the biodiversity in forest fragments in India versus biodiversity in surrounding shade-grown coffee plantations.

“The coffee plantations often have native shade trees, meaning that boundaries between fragments are very fuzzy,” Bhagwat told Mongabay.com. “For creatures like bats, birds, butterflies this means that forest fragments and coffee plantations are just one continuous landscape.”

Shonil Bhagwat. |

This led him to wonder if the methods and philosophy behind th coffee plantations could be translated to other crops, preserving biodiversity worldwide.

“Admittedly, we might not be able to grow rice under shade trees, but the principle of agroforestry has several implications for biodiversity management in highly human-dominated landscapes. Studies have suggested that forested landscapes are pretty good at maintaining biodiversity if the tree cover is above 30%. In other words, if rice fields were surrounded by hedgerows, woodlots and forest patches, then there will be much more biodiversity in the landscape,” explains Bhagwat.

Furthermore, Bhagwat believes that such a system of agriculture would also help mitigate climate change (“agricultural land partly covered in trees will fix more carbon than land without trees,” says Bhagwat), alleviate poverty, and prevent future food shortages.

“First of all, we need to get our priorities right – we have paid too much attention to economic concerns and less so to social and environmental concerns. Secondly, we need to distribute food better to address the huge gulf between the haves and have nots. Thirdly, we need to sort out our food trade and make sure that we give importance to growing food locally rather than transporting it thousands of miles, half way across the globe,” Bhagwat says. “Once these changes are in place, growing food locally, using fewer agrochemicals, and caring for the wildlife on farmland will all make sense. If these changes do not happen, and we carry on with the business-as-usual, then we are likely to face severe food shortages in the future, particularly in poorer countries.”

Food crises like those in Eastern Africa and Guatemala, affecting millions of people, have been exacerbated by cropland and local resources being used for producing trade crops rather than food to meet local needs.

Coffee agroforestry in India. Photo by: Shonil Bhagwat. |

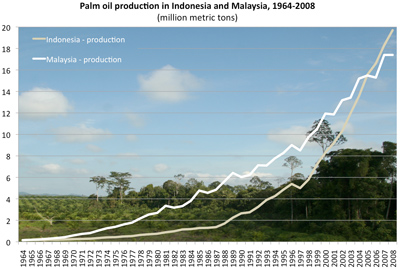

Bhagwat says that his studies on agroforestry could even apply to palm oil, a crop now made infamous for its spread across Southeast Asia leading to widespread deforestation.

By taking on palm oil, Bhagwat recognizes he may be stepping on a mine field: “Oil palm expansion is portrayed by NGOs as a classic case of environmental destruction. The industry, however, is expanding in such a way that there is no end in sight. This makes the debate about oil palm extremely polarised – with two camps almost reaching each others’ throats.”

However, Bhagwat believes that the use of agroforestry practices could make palm oil both economically viable and sustainable . Looking at the natural history of the oil palm, Bhagwat and his team found that oil palm trees first grew in tropical Africa “in mixed open forest stands with other species.”

He suggests that there are three ways in which the palm oil industry could move from intensified agriculture to agroforestry: “(1) maintain mature plantations by replacing dying or dead trees with mixed-tree stands to create forest habitat within plantations, (2) establish young plantations mixed with native trees on degraded land, and (3) set aside areas for regeneration of natural forest during future expansion of plantations.”

Oil palm plantation in Malaysia. Photo by: Rhett A. Butler. |

Bhagwat says that the current model of massive intensified palm oil plantations on the one hand and wildlife parks on the other does not give the world’s biodiversity anyplace to move from one forest to another, essentially stranding them in pockets of habitat.

“We have to remember that we are only one of the millions of species on this planet; and as the most dominant species on earth to date, we have some responsibility towards others,” Bhagwat says.

In a September 2009 interview, Mongabay.com spoke with Bhagwat about ‘land sparing’ versus ‘land sharing’ in regards to conservation, the importance of agroforestry for biodiversity and humanity, and how agroforestry could transform the palm oil industry.

INTERVIEW WITH SHONIL BHAGWAT

Mongabay: What is your background?

Shonil Bhagwat: I grew up in the vicinity of India’s Western Ghats mountain range. My first degree was in Botany and I got interested in plant ecology during my undergraduate years. While wandering in the forests of Western Ghats as a student, I soon discovered that there are many interesting creatures – not just plants – in forests and started to get involved in the wider arena of biodiversity. It was around the same time that Edward O. Wilson’s book The Diversity of Life was published. This fuelled my interest in biodiversity even further and I was attracted to its conservation. I was fortunate enough to be able to travel for almost one year across India visiting national parks, biosphere reserves and sacred sites – groves, forests, lakes, meadows, mountains and rivers. My journey to the nooks and corners of India – its mountains and coast, vast desserts and tiny islands, forests and fields – affirmed my conviction for a future career in biodiversity conservation.

Subsequently, I won a Rhodes Scholarship in 1997 to study at Oxford. I did a masters degree followed by a doctorate at the University of Oxford and have been in Oxford ever since. It is in Oxford that I became interested in ‘cultural landscapes’ – landscapes that are shaped by human activity for millennia – a phenomenon commonplace across Europe. This interest led me to return to the Western Ghats for my doctorate research and investigate biodiversity found in sacred groves – patches of forest preserved by local people for their cultural, religious and spiritual significance. I was interesting in finding out whether these patches also play a role in biodiversity conservation.

Mongabay: How did you become interested in the tension between biodiversity and agriculture?

Sacred grove in India. Photo by: Shonil Bhagwat. |

Shonil Bhagwat: I became interested in biodiversity in agricultural landscapes when working on sacred groves. These groves are usually tiny fragments of forest, many of them less than a hectare in size. As a scientist, I decided to apply the Theory of Island Biogeography (proposed by Robert H. MacArthur and Edward O. Wilson in 1967) to these forest fragments and investigate whether small patches far away from large forest have lower biodiversity than large patches close to large forest. What I found, however, was in complete contradiction to theory. I soon realised that there was one factor I had completely overlooked – shade coffee plantations around sacred groves. The coffee plantations often have native shade trees, meaning that boundaries between fragments are very fuzzy. For creatures like bats, birds, butterflies this means that forest fragments and coffee plantations are just one continuous landscape. Naturally, there was no difference whatsoever between species diversity in sacred groves (forest fragments) and species diversity in coffee plantations (landscape matrix).

I started to ask: if coffee plantations are so useful in maintaining biodiversity in the landscape, can we manage other agricultural landscapes in the same fashion? This led me to investigate the potential of agroforestry systems in biodiversity conservation. Admittedly, we might not be able to grow rice under shade trees, but the principle of agroforestry has several implications for biodiversity management in highly human-dominated landscapes. Studies have suggested that forested landscapes are pretty good at maintaining biodiversity if the tree cover is above 30%. In other words, if rice fields were surrounded by hedgerows, woodlots and forest patches, then there will be much more biodiversity in the landscape compared to when rice fields are surrounded by degraded grassland or wasteland. In a nutshell, maintaining that heterogeneity – a mixture of open and closed landscape – is the key to effective biodiversity conservation.

Rice paddies in Laos. Photo by: Rhett A. Butler. |

Mongabay: You’ve spent a lot of time doing research in India’s Western Ghats. What draws you to this place?

Shonil Bhagwat: The most amazing thing about India’s Western Ghats is its diversity – not just the mountains, valleys and rivers, but the diversity of landscapes, people and culture. The northern Western Ghats have more seasonal climate and have extremely rugged and dry mountains while the southern Western Ghats are lush green with evergreen forests. The mountain chain straddles six Indian states, each with it own culture, customs and cuisine. When you travel in the Western Ghats you meet this shear variety – on top of its biodiversity, which has made it one of the world’s biodiversity hotspots.

LAND SPARING VS. LAND SHARING

Mongabay: What would your definition be of a ‘pristine forest’?

Shifting cultivation of the Trio tribe in the Guyana Triangle in Suriname. Photo by: Rhett A. Butler. |

Shonil Bhagwat: Well, the truth is there is no such thing as ‘pristine’ forest. Humans have been around for loo long to leave anything in its original state. We have changed the earth remarkably in the last two-hundred years of industrialisation, but our predecessors have changed earth’s ‘natural’ landscapes for at least 100,000 years. Archaeology and palaeoecology of many of these landscapes gives an insight into the past. With such long-term information, landscapes thought to be untouched often turn out to have had human presence. For example, palaeoecological data suggest that sacred groves in the Western Ghats might be only 500 years old. However, peoples’ memory doesn’t go that far and if you ask them about the age of sacred groves you often get an impression that the groves have been around for ever.

Mongabay: Can you explain the difference between ‘land sparing’ and ‘land sharing’?

Shonil Bhagwat: Land sparing is what we do in over 100,000 protected areas around the world. We allocate this land for conservation in the hope that the spared land will harbour world’s biodiversity. What we also do in the process is that we intensively cultivate the non-spared land in the hope to produce as much food out of it as possible. Land sharing – as in sharing the earth with millions of other species – is a different approach to managing human-dominated landscapes. In Michael Rosenzweig’s words, it is about creating space for biodiversity where “people live, work and play”. It is about enhancing the quality of non-spared land so as to maintain biodiversity.

Mongabay: What countries would you point to as being especially effective in land sharing?

Tea plantation in Uganda. Photo by: Rhett A. Butler. |

Shonil Bhagwat: There is probably none. The way world practices its agriculture needs an overhaul according to a recent report by an intergovernemental panel of over 400 agricultural experts. We have paid too much attention to the economic gains from land, but very little to environmental and social concerns. This has reflected in our agricultural policies and practices, which rely heavily on the use of agrochemicals and intensification to produce more and more food. Ironically, we waste a lot of it! For example, one third of food bought in UK supermarkets is thrown into the bin. So the problem of feeding the world is clearly not that of producing more food, but that of distributing it better – particularly to the poor.

In addition, we need to grow food in such a way that environmental concerns are also addressed. The Millennium Ecosystem Assessment has suggested that we have probably exhausted the fertility of land by using agrochemicals and to produce yields similar to those in the 1960s (before the green revolution) we now need twice as much land and in some cases even more. This means intensification hasn’t worked – we have lost productivity of land, but also caused environmental destruction in the process of expanding land required for agriculture. This is a double whammy, and surely we need to find better ways of growing food. Land sharing or wildlife-friendly farming is one way of addressing the environmental concerns. If this is combined with organic agricultural practices free of agrochemicals, then we can also maintain productivity of the soil by, for example, fertilizing it with green manure. There are studies comparing yields of organically grown good vs. food grown in conventional way on intensively managed land. The results suggest that yields per unit area of land, interestingly, are not that different. So why not grow all food organically and still feed the world? Something for agriculturists to think about.

I am not an expert on agriculture, but from the perspective of biodiversity conservation I can say that we need to get our act together on growing food more responsibly – this is where agriculturists and conservationists need to work together.

Mongabay: Are there some species that require ‘land sparing’ in order to survive? If so, what are some examples?

Soy fields and the Amazon. Photo by: Rhett A. Butler. |

Shonil Bhagwat: It is important to say that ‘land sparing’ and ‘land sharing’ are not alternatives – they are complementary. The problem is that we have pretty much reached the upper limit when it comes to sparing more land for conservation. Many countries simply cannot allocate more land for protection in reserves. This is why we are in need of ‘land sharing’ to enhance biodiversity value of land outside reserves.

There are many species which have large home ranges (examples include charismatic species such as elephant, a large herbivore; tiger, a large carnivore and many more). These species simply cannot survive in agricultural landscapes and require large extent of their suitable habitat under protection. Essentially, their survival is dependent on land sparing. However, there is a large majority of species that can be perfectly content with living in mixed landscapes. Those are the ones that will respond to ‘land sharing’ practices.

What we need to bear in mind is that there are several constrains on conservation. Understandably, countries have competing economic interests and cannot always go on sparing more land. This is when we need to explore ‘land sharing’ alternatives. There is no ‘silver bullet’ for conservation – we have to use as many ways as are needed to get the job done.

Mongabay: Why is ‘land sharing’ especially important when it comes to climate change?

Shonil Bhagwat: The prospect of climate change has really woken us up. People take things seriously when they can see them happening in their backyards. Climate change is one such thing; biodiversity conservation probably not. Conservationists, therefore, need to align their interests with climate change community. As I have explained above, land sharing is important for biodiversity conservation, but it is also important to mitigate climate change. Take the case of carbon sequestration. Agricultural land partly covered in trees will fix more carbon than land without trees – a good case for keeping trees in the landscape. From conservation perspective, these trees have to be diverse and native (not just one species planted over thousands of hectares). So if we were to align interests of conservation and climate change communities, then the solution is to grow a variety of native trees on agricultural land – a win-win solution to both problems.

Mongabay: What is countryside biogeography (also known as reconciliation ecology or conservation biogeography) and what role could it play in conservation of the ‘land sharing’ type?

Mix of forests, estuaries, and agriculture. Photo by: Rhett A. Butler. |

Shonil Bhagwat: These are all various ways of describing ‘land sharing’ practices. Countryside Biogeography is Gretchen Daily’s phrase (coined in 2001) while Reconciliation Ecology (coined in 2003) is Michael Rosenzweig’s. Conservation Biogeography (2005) has a much broader remit, but also includes conservation management on agricultural land. The principle behind these various proposals is managing human-dominated landscape in a way that also supports conservation of species other than humans – we have to remember that we are only one of the millions of species on this planet; and as the most dominant species on earth to date, we have some responsibility towards others. This is the philosophy behind ‘land sharing’.

AGROFORESTRY

Mongabay: What is agroforestry? How is it different or similar to land sharing?

Shonil Bhagwat: Agroforestry is intentional management of native trees in agricultural landscapes. It is a practice of ‘land sharing’ in human-dominated forest landscapes. If we interpret agroforestry more broadly, this management of native trees includes any native tree – whether standing alone in a field, or living with other trees in a woodlot, or present within a forest fragment in agricultural landscape with a whole lot of other creatures. I am in favour of this broad interpretation of agroforestry – simply meaning a sensible combination of agriculture (growing food crops) and forestry (growing native trees).

Mongabay: What are the differences in biodiversity between agroforestry and primary forest? What species fare better in which systems?

Shonil Bhagwat: As a rule of thumb, habitat generalist species fare better in agroforestry systems and habitat specialists not so well. However, surprisingly, if you look at the published literature on agroforestry, many studies report very high similarity (as much as 100% for some taxa in some cases!) between agroforestry and primary forest. This means a large majority of biodiversity we are interested in conserving is present right under our noses – as long as there are conditions suitable for their survival. Our job really is to create those conditions in as many ways as we can.

Mongabay: What are some crops that are currently being grown through agroforestry? Are there other crops that could fit this model that aren’t being grown in this way?

Corn grown over rainforest habitat in Belize. Photo by: Rhett A. Butler. |

Shonil Bhagwat: Agroforestry is routinely practised for commodity crops – coffee and cocoa are the most popular examples. The principle of agroforestry – interpreted broadly as I suggest above – can apply to managing any agricultural landscape and growing any crop. For example, we cannot grow wheat under shade trees, but we can maintain hedgerows, woodlots and forest patches around wheat fields. To me, this qualifies for agroforestry. All we need to ensure is that the agricultural landscape is as heterogeneous as possible with a variety of small land parcels of fields and forests mixed together with human settlements. What we don’t need is hundreds and thousands of hectares of intensively managed agricultural land because this is not good for biodiversity, particularly in tropical forest landscapes. Land sharing is a different approach to growing food and can, in my opinion, be applied to any crop.

Mongabay: What methods or incentives would you suggest to promote the growth of agroforestry?

Shonil Bhagwat: Well, we need a sea change for this to happen. First of all, we need to get our priorities right – we have paid too much attention to economic concerns and less so to social and environmental concerns. Secondly, we need to distribute food better to address the huge gulf between the haves and have nots. Thirdly, we need to sort out our food trade and make sure that we give importance to growing food locally rather than transporting it thousands of miles, half way across the globe. This is not to say that we don’t need trade – many poor countries do benefit from trading with richer ones – but we need to be sensible about it.

Once these changes are in place, growing food locally, using fewer agrochemicals, and caring for the wildlife on farmland will all make sense. If these changes do not happen, and we carry on with the business-as-usual, then we are likely to face severe food shortages in the future, particularly in poorer countries.

I am not an economist, but there is a widespread feeling that the present economic model is not fair to a large population of the world. To promote the growth of ‘land sharing’ practices it is the present economic model that needs an overhaul. This one is really for the economists to think about.

OIL PALM

Mongabay: What led you to recently begin studying the palm oil boom in Southeast Asia?

|

Shonil Bhagwat: Oil palm expansion is portrayed by NGOs as a classic case of environmental destruction. The industry, however, is expanding in such a way that there is no end in sight. This makes the debate about oil palm extremely polarised – with two camps almost reaching each others’ throats. I was intrigued by this debate and thought: surely, there must be a middle path. I thought that agroforestry, interpreted broadly as keeping native trees in agricultural landscapes, can pave the road to sensible management of oil palm plantations. This is when we started to look at the past history of landscapes in hinterlands of wet tropical Africa, where oil palm originally belongs. The history suggests that oil palm grows in mixed open forest stands with other species. Its expansion in West Africa can be attributed to change in climate as well as human activity. Together, these triggered the spread of oil palm.

The present expansion of oil palm is admittedly on a much grander scale, but can we apply our understanding of the ecology of this species to its present-day management? This is why we suggested agroforestry as a possible solution to management of oil palm landscapes.

Mongabay: How can conservation be practiced around these plantations, which are considered ecological deserts by many biologists?

Shonil Bhagwat: Indeed, biodiversity data from these plantations has shown them to be extremely poor – ecological deserts might not be an exaggeration. But compare this with jungle rubber (also a tree) plantations grown in exactly the same environment in south-east Asia. There is much more biodiversity in jungle rubber than in oil palm, mainly because jungle rubber is grown with other species native to forests of south-east Asia.

Admittedly, oil palm has different ecological requirements to jungle rubber. However, the principle of growing tree crops with native forest species can be applied to oil palm. We see three ways in which agroforestry principles can be applied to oil-palm landscapes: (1) maintain mature plantations by replacing dying or dead trees with mixed-tree stands to create forest habitat within plantations, (2) establish young plantations mixed with native trees on degraded land, and (3) set aside areas for regeneration of natural forest during future expansion of plantations. This diversity of approaches to plantation management will be essential if oil-palm landscapes are to act as buffers and corridors connecting intact forest reserves. This is how oil-palm plantations will need to be managed in a ‘land-sharing’ approach.

Palm oil is beginning to expand past southeast Asia: aerial view of palm oil plantations in Costa Rica. Photo by: Rhett A. Butler. |

The alternative suggested to manage oil palm landscapes is more along the lines of ‘land sparing’ – creating reserves to compensate for large chunks of land taken up for oil palm plantation. But in this approach connectivity between reserves is overlooked. In other words, oil palm plantations will continue to remain ‘ecological deserts’ while the ‘ecological oases’ (reserves) will be located far away from each other. The question is: how can species travel between the two oases if there is vast desert in between? That’s the reason why I am in favour of ‘land sharing’ approach to manage oil palm plantations.

Mongabay: Would practicing agroforestry with palm oil provide any unique challenges?

Shonil Bhagwat: The main challenge is reduced yields. In the agroforestry scenario, the yields will no doubt reduce. However, the alternative to agroforestry is not any better when it comes to reduced yields. The reserves created to compensate for expansion of oil palm plantations will naturally take up land where oil palm could have been grown – thereby levying an opportunity cost on plantations. So in either case we cannot overcome the problem of reduced yield whether due to reduced area (allocated to reserves) or reduced sunlight (allocated to shade trees in mixed agroforestry plantations).

There can be three ways in which the loss can be compensated and the problem of reduced yields addressed: (1) higher prices for palm oil, (2) market incentives for biodiversity-friendly palm oil, and (3) improved varieties of oil palm that perform well in mixed plantation matrix. How can we bring about these three? There is food (or oil?!) for thought for agronomists and economists.

Mongabay: What advice would you give conservation organizations in going forward: should they focus on ‘land sparing’ or ‘land sharing’ or some combination of the two?

Shonil Bhagwat: In my opinion, a variety of management practices (including a combination of land-sparing and land-sharing) is likely to prove more beneficial for biodiversity in oil-palm landscapes than one approach alone. This brings us back to diversity, this time diversity of management approaches. There is no ‘silver bullet’ – we have to find ways of managing oil palm landscapes that get the job done.

Related articles

Global campaign has planted 7 billion trees

(09/23/2009) The campaign to plant seven billion trees has achieved its goal, the United Nations announced Tuesday. 7.3 billion trees have been planted in 167 countries since the UN Environment Programme (UNEP) launched the initiative in 2006. The effort aimed to sequester vast amounts of carbon from the atmosphere while generating benefits for human populations and wildlife.

Trees sprout across farmland worldwide

(08/26/2009) Half the planet’s farmed landscapes have significant tree cover, reports a new satellite-based study. The research, conducted by the Consultative Group on International Agricultural Research’s World Agroforestry Centre found that tree cover exceeds 10 percent on more than 1 billion hectares of farmland, indicating that agroforestry is a “vital part” of worldwide agricultural production. 320 million hectares of forested agricultural land are found in Latin America, 190 million hectares in sub-Saharan Africa and 130 million hectares in Southeast Asia.

Unique acacia tree could play vital role in turning around Africa’s food crisis

(08/24/2009) Scientists have discovered that an acacia tree, long used by farmers in parts of Africa, could dramatically raise food yields in Africa. The acacia tree Faidherbia albida, also known as Mgunga in Swahili, possesses the unique ability to provide much-needed nitrogen to soil.

Farmers have poor understanding of role of wildlife in protecting crops

(08/10/2009) Environmental conservation depends, to a large degree, on public acceptance. Understanding people’s opinions on ecosystems and wildlife can be very helpful in designing programs that aim to benefit both the environment and society. A new study, published in Tropical Conservation Science, interviewed organic shade-coffee farmers in Cuetzalan, Mexico, to understand how they perceive the wild animals that live in their fields, as well as their knowledge of the ecological roles these species play in maintaining ecosystem services.

Turning wasteland into rainforest

(07/31/2009) The highly touted reforestation project launched by orangutan conservationist Willie Smits in Indonesian Borneo is detailed in this week’s issue of Science.

Ecological Cacao? Thinking about all sides of your chocolate bar

(04/01/2009) As concern for the preservation of forest eco-systems in the tropics has increased over past decades, there has been a growing consideration for ways to harmonize tropical agricultural production with the surrounding environment. The idea of shade grown products, especially coffee and cacao, have become the focus of scientific study and of marketable interest for environmentally conscientious consumers. However, the practical and dependable nature of the practice of shade growing for farmers and conservation objectives is still the matter of some debate.

Sustainable farming is the only way to feed the planet going forward

(02/05/2009) Embracing more sustainable farming methods is the only way for the world’s farmers to grow enough food to meet the demands of a growing population and respond to climate change, the top crop expert with the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) said today.

Shade-grown coffee preserves native tree diversity

(12/23/2008) A new study finds that shade-grown coffee protects the biodiversity of tree species, as well as those of birds and bats. Published in Current Biology, the study found that native trees in shade-grown coffee plantations aid the overall species’ gene flow and can become a focal point for reforestation.

Carbon market could pay poor farmers to adopt sustainable cultivation techniques

(11/26/2008) The emerging market for forest carbon could support agroforestry programs that alleviate rural poverty and promote sustainable development, states a new report issued by the World Agroforestry Center (ICRAF).

Rainforest agriculture preserves bird biodiversity in India

(11/04/2008) Conservation of biodiversity and agriculture have long been considered conflicting interests. Numerous studies have shown that when agricultural replaces a forest, biodiversity greatly suffers. However a new study finds it doesn't have to be that way.

Eco-friendly shade-grown coffee buffers farmers against climate change

(10/03/2008) Shade-grown coffee plantations will be more resistant to climate change than conventional plantations, report researchers writing in the journal Bioscience. Shade grown coffee is already lauded for its environmental benefits including supporting high levels of biodiversity and requiring less fertilizers and pesticides.

Coffee plantations may preserve tropical bird species

(06/18/2007) Agricultural areas offer opportunities for conservation in deforested landscapes in the tropics, reports a study published in the April 2007 issue of the journal conservation Biology by Stanford University biologists.