Efforts to protect the world’s largest and rarest species of zebra — Grévy’s Zebra (Equus grevyi) — hinge on engaging communities to lead conservation in their region, says a Kenyan conservationist.

Belinda Low, Executive Director of the Nairobi-based Grevy’s Zebra Trust, says her group’s programs, which employ members of local communities as scouts and conservation workers, are helping maintain dialog between communities while providing new opportunities for education and employment. Grevy’s Zebra Trust is working with communities to plan livestock grazing so that it can be used as a tool to replenish the land, rather than degrade it, “by ensuring that plants have adequate recovery time, and to break up bare, capped soil using livestock hooves so that rainfall capture improves and the right conditions are created for seeds to establish,” Low explained. “This approach actually strengthens the pastoral way of life and in the long-term will strengthen the resource base that livestock (and thus community wealth) depends on.”

Belinda Low |

Thought to number less than 3,000 individuals, Grevy’s Zebra is primarily endangered due to degradation of its arid and semi-arid grass and shrubland habitat, increased hunting due to an influx of automatic weapons, and disease, which is exacerbated by loss of quality habitat. Its range includes an active conflict zone in southern Ethiopia and some parts of northern Kenya, a factor that has historically complicated conservation efforts.

In a September interview with mongabay.com, Low spoke about the Trust’s efforts to protect Grevy’s Zebra and its habitat while simultaneously helping local communities. Low will be presenting at the upcoming Wildlife Conservation Network Expo in San Francisco on October 3rd.

INTERVIEW WITH BELINDA LOW

GZT Grevy’s zebra scout collecting data |

Mongabay: What is your background and why did you choose Grevy’s Zebra?

Belinda Low: I was born and raised in Kenya. My parents always took my brother and I on safari as babies and regularly as we were growing up, so my childhood was instrumental in shaping my love of wildlife and wild places and in particular my connection with Kenya. I did a four-year undergraduate degree in Hispanic Studies during which time I lived in Ecuador for a year studying language and literature at a university in Quito. A chance meeting with an American biologist in South America who told me the world was my oyster opened up the possibility of getting into conservation. I enrolled in a master’s degree program in Conservation Biology at the Durrell Institute of Conservation and Ecology at the University of Kent, UK in 1999. After graduating, I returned straight home to Kenya and received a call from Lewa Wildlife Conservancy shortly afterwards asking me if I would be interested in studying zebras and I thought why not? The study was looking at competition between plains and Grevy’s zebra and sounded really interesting, particularly as Grevy’s zebra is endangered. At the time I was not aware of the serious decline that Grevy’s zebra had undergone in my own lifetime as I had seen them regularly in Samburu when I was growing up and none of my family or friends in Kenya or abroad were aware either.

Mongabay: What distinguishes Grevy’s Zebra from other zebra species?

Grevy’s Zebra. Courtesy of Grevy’s Zebra Trust  Plains Zebra. Photo by Rhett A. Butler |

Belinda Low: Well, I probably sound biased, but Grevy’s zebra are much more impressive to look at! They are the largest of the three zebra species found in Africa (the other two being the plains zebra found in grasslands throughout sub-Saharan Africa and the mountain zebra found in the mountain grasslands of South-West Africa). The main differences are that Grevy’s zebra stripes are much narrower, they have white bellies, very large, rounded ears and brown muzzles.

Socially they are also quite different. Because they live in semi-arid and arid environments, resources within their range are patchily distributed. Breeding males therefore defend territories containing water and grazing resources that are required by females, while surplus males move around in bachelor herds. Females are separated by the needs of their reproductive status, for example, lactating females need to be near water so that they can produce enough milk for their foals, while non-lactating females can afford to seek pastures further away. Grevy’s zebra are therefore socially fluid unlike the other two zebra species which are water-dependent and organized in tight-knit harems.

Mongabay: The population of Grevy’s Zebra has declined significantly in recent decades, what are presently the biggest threats to the species? Do you see risks to Grevy’s Zebra from climate change?

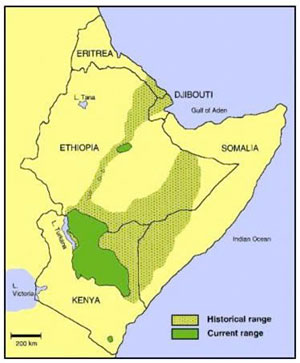

The historic and present distribution of Grevy’s zebra in the Horn of Africa (data assimilated from Kingdon, 1979, 1997; Yalden et al., 1986). Map and caption courtesy of the Grevy’s Zebra Trust |

Belinda Low: Threats vary in type and severity across the range of Grevy’s zebra. For example, the more northern populations where there are ethnic groups that eat zebra are most threatened by illegal killing because firearms have increased and hunting is no longer fair game. In Samburu, where it is taboo to eat single-hoofed animals, Grevy’s zebra are not hunted. However, they are most under threat there from loss of habitat due to land degradation and more recently from disease, which is actually brought on by the decline in resources in three ways: Grevy’s zebra lose body condition which increases their susceptibility to disease; when they are forced to graze very close to the soil, the risk of ingesting anthrax spores increases; and with animals concentrated in smaller areas with the remaining resources, their exposure to parasites increases. Finally, access to water is a major issue threatening the survival of foals [young zebra]. Females tend to time births with the wet seasons when resources are available, however, in years when rains fail, the grazing areas are located far from water and the journey that females and foals have to make is a long one, placing an energetic strain on the foals which can lead to high foal mortality.

I think your question about climate change is a really good one and I’d like to answer it in two parts. First, in a global context, the impact that the whole world has on this planet is extremely significant for an endangered species like Grevy’s zebra because it lives in such a fragile ecosystem. So in a sense, yes, there is a risk to Grevy’s zebra from climate change because already the rangelands which they depend on are rapidly deteriorating. If rainfall becomes more erratic and decreases, our work to rehabilitate rangelands becomes even more challenging.

Poached Grevy’s zebra being discussed by herders and the GZT team |

Second, I think there is a tendency to blame climate change for the increase in severity and frequency of the droughts we experience when actually they are largely human-induced: with denuded rangeland, any rainfall received either runs off or evaporates. So the key is to recover plants in order to cover bare soil so that what rain does fall it is captured. If the rangeland was covered in grass and we had a bad rainfall year, people would just refer to it as a dry year rather than a drought. The other benefit of covered soil is that it harnesses carbon and thus can help to mitigate climate change but unfortunately the importance of the role of grasslands in carbon capture is often ignored. So as far as Grevy’s zebra are concerned, focusing on recovering the rangeland through planned grazing is critical to their future. While we cannot control the amount and timing of rainfall, we can control the effectiveness of that rain when it hits the ground, and that is going to be key in recovering plants.

Mongabay: Has conflict in Ethiopia had an impact on Grevy’s Zebra?

Digging wells for Grevy’s zebra during the drought |

Belinda Low: Yes, but there are two sides to this coin. On the one side, conflict between rival ethnic groups has had a negative impact. For example, some pastoral groups will camp at water to protect themselves better from being raided. This prohibits access to water for Grevy’s zebra and in the dry season is a serious cause of mortality. Some groups also eat Grevy’s zebra as subsistence food and because they are well-armed for fighting, a zebra has no chance against an automatic rifle.

On the other side of the coin, water and grazing resources in conflict-torn areas tend to be in good supply because pastoralists are unable to stay for long due to the insecurity. So Grevy’s zebra and other wildlife get the chance to flourish in these circumstances, but they live in constant fear of man.

Mongabay: Given that human populations in the region are desperately poor and often dependent on livestock, what are your strategies to compel local people to care about wildlife? Are there community benefits from conservation?

Belinda Low: There are several strategies that we use. Communities are our primary partners in our projects and we engage them in several ways. One is through employment as Grevy’s Zebra Scouts or Ambassadors where their role is to provide protection for Grevy’s zebra, raise local awareness about their conservation status and monitor them. These employment opportunities are highly prized and through the network of scouts and ambassadors, significant awareness has been raised causing positive behavior changes towards the species. Both the Grevy’s Zebra Scout and Ambassador Programs are complemented by our secondary school education scholarship program called the Grevy’s Zebra Bursary Programme. Education opportunities for children living out in these remote areas are few so we are able to offer support and link it directly to Grevy’s zebra, which again results in creating positive attitudes towards the species.

Grevy’s Zebra Scouts with Belinda Low (left) and Martha Fischer (right)  Belinda Low with West Gate Community |

There is one area that we are working in where ethnic tensions flare up periodically. We have both sides of the conflict employed on our Ambassador team and they are making a lot of progress in maintaining dialogue between the two groups. Grevy’s zebra is therefore used as an entry point to discuss peace and resolution going forward. We also support the work of an indigenous NGO in Ethiopia called WildCODE who have also successfully used Grevy’s zebra conservation issues to facilitate discussions on creating peace in the region of Chew Bahir. Many of the elders in the various ethnic groups that they work with recognise that Grevy’s zebra and other wildlife have seriously declined and they want to take action to prevent their complete disappearance. A first step to doing that is creating a stable environment.

When we first start working with a community, we have a meeting where we discuss Grevy’s zebra, during which we learn about their knowledge of Grevy’s zebra and we share our own. One of the things we ask about is the role of Grevy’s zebra in culture. This often leads to traditional songs and dances being performed in which Grevy’s zebra are the theme and it serves to remind everyone of how intertwined cultural traditions are with this species, thus reviving their intrinsic value rather than their economic value.

Instead of viewing livestock as a problem we view it as an opportunity. As I explained earlier, for the future of Grevy’s zebra to be secured, it is critical that rangeland is recovered. But this is not just critical for Grevy’s zebra and other wildlife, it is also critical for the long-term security of pastoral livelihoods which are dependent on the same ecosystem. The Grevy’s Zebra Trust has begun working with communities to plan livestock grazing so that it can be used as a tool to regenerate land by ensuring that plants have adequate recovery time, and to break up bare, capped soil using livestock hooves so that rainfall capture improves and the right conditions are created for seeds to establish. This approach actually strengthens the pastoral way of life and in the long-term will strengthen the resource base that livestock (and thus community wealth) depends on.

Mongabay: Have you seen a positive response to your programs?

Belinda Low: Yes, we have and I’d like to quote one of the Grevy’s Zebra Scouts as an example:

Vegetation monitoring |

“Since the project started we have been seeing the goodness of the work and we enjoy it. We are learning more and didn’t know the importance of Grevy’s zebra at the beginning. Before the project started, Grevy’s zebra were afraid of livestock and people but now they are not afraid. Even the herders accept them to pass next to them. Monitoring of Grevy’s zebra was the responsibility of the scouts, but now it has become the responsibility of the whole community and they report sightings to the scouts.” Chereb Lechooriong, Grevy’s Zebra Scout, Sesia.

This is just one of many examples of positive feedback that we have had not just from Grevy’s Zebra Trust employees but also from the wider community, and community leaders.

Mongabay: What are some of the challenges of working in the field there?

GZT camp on the Barsaloi lugga in northern Kenya |

Belinda Low: What some would see as a challenge I actually enjoy. For example, we camp the majority of the time and there is nothing better than getting cleaned up and crawling into my tent after a hot, dusty day in the field. Having fresh food can be a challenge if we are out for a long time. There is always fresh meat available in the form of goats but as far as vegetables and fruit go, we can probably only go one week before even the hardy stuff starts to rot because of the high temperatures. I would say the main challenge is when an area has ethnic tensions. Although we are viewed as a neutral party, it can be dangerous for us to be operating in certain areas when conflict intensifies.

Mongabay: Do you see much potential for Grevy’s Zebra-centric tourism to generate alternative livelihoods for local communities?

Belinda Low: Absolutely and in fact, it has already started. Both the West Gate and Kalama Conservancies got their operating budgets funded thanks to their potential for Grevy’s zebra conservation. Since the conservancies began, both now have a high-end lodge established and Grevy’s zebra is one of the key marketing factors for both tourism enterprises.

Mongabay: How can people in places like the U.S. help your efforts?

Belinda Low: One of the things I love about Grevy’s zebra conservation is seeing how it connects the pastoral communities of northern Kenya with an international audience. It is a bridging of cultures and continents with the common goal of conserving this magnificent endangered species.

Grevy’s Zebra Trust community meeting  Taking samples from a sick Grevy’s zebra foal |

People can help in several ways. Raising awareness about Grevy’s zebra is vital because the more people that know, the more opportunities there are for support, and I don’t mean just funding but also new ideas and technical support. Of course, as a Trust, we rely on donations and grants to fund our work, so any financial support is extremely valuable to us, no matter its size. We also have a wish list of items such as equipment so another way is to donate those articles directly.

You could also visit Kenya and see Grevy’s zebra in the community conservancies. A percentage of the income from your stay at one of the lodges in the conservancies goes to the community for development and conservation activities. And you get the wonderful experience of both wildlife and people. If you book through the Grevy’s Zebra Trust then we would receive 20% of the income from your booking.

Finally, I think as a global community we need to minimize our impact on the planet, so that endangered species like Grevy’s zebra and the communities that they share the land with, are given the best chance for a bright future.

Mongabay: Do you have any tips for aspiring field conservationists?

Belinda Low: Yes! I would advise that if they are working in a community context then it’s vital that the local people play a leading role in developing and implementing any conservation measures because it promotes ownership and pride and this is ultimately going to determine the success of your conservation program in the long-term.

Planning livestock grazing |

There are plenty of good examples of various approaches which work and don’t work. I’d advise people not to reinvent the wheel and to build upon what other people have spent many years developing into successful and strong conservation programs.

I’d suggest that where possible you should collaborate because from my experience, two or more is stronger than one and there are always going to be gaps in your experience, knowledge and resources, which others can fill so you create a win-win situation.

Finally, there are times when one feels like the odds are against you and there’s a danger of losing hope. Don’t! It’s essential to remain positive and maintain your passion and vision because that is what will drive you to succeed.

Grevy’s Zebra Trust

Low will be presenting at the upcoming Wildlife Conservation Network Expo in San Francisco on October 3rd.