|

|

Rio Tinto’s ilmenite mine in southeastern Madagascar is among the largest on the planet. At peak capacity, its owners say, it could produce as much as 2 million tons of the stuff—worth roughly $100 a ton—each year, to be shipped off and smelted abroad. What’s left of it after refining—some 60 percent of the ore that arrives from Madagascar—will be sold for $2000 a ton as titanium dioxide, a pigment used in everything from white paint and tennis court lines to sunscreen and toothpaste. At current levels of demand, the Fort Dauphin mine will provide 9 percent of the world supply over the next 40 years, amounting to more than $60 billion of titanium dioxide. Even that is a conservative estimate: demand for ilmenite has been growing at 3-5 percent annually, with major mines slated to close in coming years and few untapped sources known worldwide.

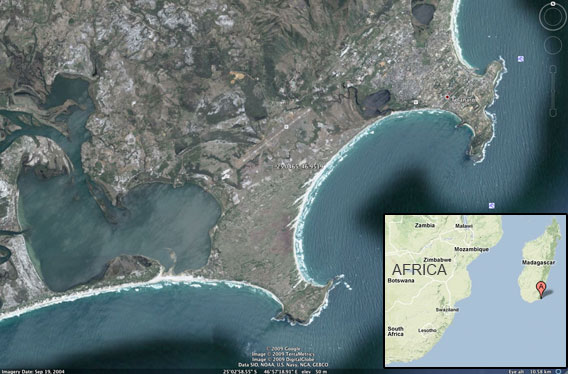

Google Earth satellite image of the mining area. Image acquired on Sept. 19, 2004.

As befits a project of this scale, Rio Tinto has developed a large, sleekly-designed website to promote the mine and accompanying port, not as beacons of industrial achievement and profitability, as one might expect, but as but as presenting tremendous “conservation opportunities,” which, the reader will discern, is not the same as conservation.

While conservation simply involves protecting existing swaths of the natural world from further degradation, creating ‘conservation opportunities’ requires a lot more groundwork. In order to create conservation opportunities near Fort Dauphin, Rio Tinto will use a floating dredge to pull up deposits of sand to a depth of 20 meters over an area of nearly 6000 hectares of coastal forest and marshes over the next forty years. As a result, they will have the opportunity to put all vegetation aside and “store the topsoil for use in rehabilitation,” or “forest restoration”—reseeding the closed mine with key species the company found in the original forest. Extracting titanium dioxide from beneath 6000 hectares of forest and wetlands has also given the company the opportunity to turn 977 hectares of habitat into three widely separated conservation zones, to be exempted from mining in order to “protect several dozen species from extinction.” It remains to be seen whether the three conservation zones in question will be large enough to sustain the species that live there.

Ringtailed lemurs are found in the Fort Dauphin/Tolagnaro region. |

And yet, reading on, the entire website seems devoted to conflating conservation and conservation opportunities. The slogan “Net Positive Impact” on biodiversity appears throughout Rio Tinto’s writings on the project, which boast of “Conservation Areas” and a “Conservation Committee” as well as an “Ecological Research Centre” and full-scale trials of “ecological ecosystem restoration.”

Rio Tinto ranked at the top of its field in last year’s Dow Jones Sustainability Index. In Fort Dauphin, their subsidiary QMM has committed to reforesting large tracts of land around the mine in order to provide a more sustainable source of charcoal and wood for construction. It has partnered with a broad set of NGOs in a program to promote vegetable farming in the region, which in turn will reduce locals’ dependence on the existing forests for their sustenance and their income. So it is important not to hurl mud at the company’s efforts to mitigate the environmental impact of what is, by and large, an ecologically disastrous industry. QMM may indeed be better than the rest, and there are signs that Rio Tinto’s practices are gradually improving. But reading the company’s glib accounts of its commitment to biodiversity, something does not compute.

In the way of a growing number of corporations operating large-scale industrial projects in beautiful places, Rio Tinto leans heavily in Fort Dauphin on the social capital afforded by the idea of environmental or biodiversity offsets (BDOs), actions taken elsewhere to counteract the negative ecological impacts of a given project. As a recent article in Mining Magazine put it, “BDOs can contribute to developing a social license to operate.” Offsets might also be described as trading “conservation opportunities” (read devastation) at a mining site for genuine conservation efforts in another area.

In the face of the largest investment in its history, the Malagasy government is unlikely to act as a watchdog on the EIA. |

Offsets seem logical enough—mining will inflict a certain amount of damage on the landscape, and mining companies should be held to account both for cleaning up the mess and for compensating for the damage their project entails. But offsets can also be a distraction from the stakes of a particular project: protecting antelope in Montana will never bring back the wolves you lose in Idaho, and offsets take for granted the premise that the existence and scale of the offending project are non-negotiable. Moreover, offsets invite companies to make measurable tradeoffs in the service of a concept—biodiversity—to which the very idea of trades is alien. How does one calculate the value of a lost plant or animal species? How does one calculate the value of a biodiversity offset?

From Rio Tinto’s literature: “The total residual impact is calculated by measuring the area and quality, or condition of habitat, of biodiversity value likely to be lost after the mitigation hierarchy has been followed.” In order to establish the likely residual impact of its project, Rio Tinto conducted “extensive baseline research” on-site in the late 1990s in preparation of the environmental impact assessment it submitted to the Malagasy government in 2001. But the company’s presence in the affected area began some 15 years earlier, with exploratory drilling and road construction. According to the Mining, Minerals, and Sustainable Developments Project, then, Rio Tinto has acted true to industry form: “Often the EIA is not carried out until after detailed exploration or even development drilling, by which time the site can be covered by a network of roads, making it impossible to establish true baseline data.” It was not until 2001 that Rio Tinto formed an “Independent Biodiversity Committee” to evaluate the project’s offset and mitigation measures. Before that, environmental research was conducted by a team on the company payroll with obvious incentives to understate the conservation value of the mining area and play up the potential of mitigation efforts.

Verreaux’s Sifaka, a lemur known for its “dancing”, lives in the vicinity of Fort Dauphin/Tolagnaro. |

The operative assumption of QMM’s Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) is that areas around the mining site, composed of littoral forest, sparse woodlands, and savannah, have been extensively deforested since humans first populated the region. Regardless of mining, the company projected that deforestation would wipe out the forest ecosystems in the area by 2040. But research published this summer in Conservation Letters suggests that the patchy makeup of the littoral forest may be due to historical droughts rather than deforestation, and that “such areas of ecological discontinuities are adaptive components for diversity, evolution, and persistance in variable environments (Noss 2001; Pressey et al. 2007).” Malika Virah Sawmy, a researcher at Oxford University, analyzed 6000 years of pollen samples at four sites around Fort Dauphin in order to reconstruct a history of deforestation in the area. “The view that may have influenced the clearance of the southern littoral forest for mining,” she writes, is “that this forest has been declining from prehistoric to present times due to anthropogenic activities.”

Thus, we find a map in a joint publication of Rio Tinto and the World Bank which details the relative quality of forest fragments within the mining areas. It shows fragments of “good condition,” “partially degraded” and “very degraded” forests with intervening gray areas that one assumes are of negligible conservation value. Yet viewed through the lens of Virah Sawmy’s research, it becomes harder to distinguish between “good condition” and “degraded” (patchier) forest, and the intermittent unforested gray areas must be considered as part of the whole.

Evidence drawn from satellite imagery casts further doubt on the analysis of deforestation presented in QMM’s EIA. Virah Sawmy cites two studies that argue that QMM’s presence in the region has accelerated deforestation—by undermining land tenure rights of local groups, increasing accessibility to forest areas through road construction, and prompting an influx of migrant workers.

Much of the ecological destruction and pilfering of poor populations that occurs worldwide is tied to some nameless product like “titanium dioxide” which comes to be and enters the global marketplace anonymously, sold by companies we don’t know to the companies from which we buy our toothpaste without any record of its origin or method of production. This practice is at the root of the general consumer apathy towards issues like mining, logging, and industrial agricultural development. |

Virah Sawmy herself acknowledges that “the benefits of biodiversity offsets are potentially large” and writes that “they will play an important role in responsible mining.” Still, the evidence she brings to bear on the region near Fort Dauphin demonstrates a key danger of writing off ecological damage with biodiversity offsets: we just don’t know much about the ecology of areas we are mining. Rio Tinto’s claims that work it has funded “has resulted in making these littoral forests some of the best known ecosystems in Madagascar” simply aren’t believable. Even if true, this is a moot point now that mining is underway. “The idea of area equivalence for biodiversity offsets does NOT work well in a region with high local endemicity, unique composition and high heterogeneity in terms of biodiversity,” Virah Sawmy said in an email.

If mining companies like Rio Tinto are sincere in their commitment to biodiversity and sustainable development, then efforts to study and analyze the potential impacts of a mining project on the surrounding ecosystems ought to coincide with the earliest stages of exploration. This is the true baseline, and it will give the same depth to research about the ecology of a potential mining site as research into its extractive potential.

Rio Tinto writes in a pamphlet on biodiversity offsets that it believes offsets to be “inappropriate where the operation impact is on completely irreplaceable biodiversity values.” That much seems obvious, but if the “biodiversity values” in question are truly “completely irreplaceable,” then is it appropriate’ to destroy them for a 40 year supply of white paint? Especially, that is, when the product leaves Madagascar at $100 a ton to be sold at the next stage of refinement for twenty times as much. If the mining giants were sincere in their commitment to biodiversity, then surely there would be some instances in which the “biodiversity values” of a place outweigh the value of the minerals it contains.

But if, as I suspect, they are not sincere, then we cannot let them cling to the banners of “sustainability” and “biodiversity” with impunity. You cannot offset ecological damage indefinitely: there is only so much planet to go around. The true tradeoff lies not in biodiversity offsets, as they would have us believe, but in the choice between true conservation and industry, which, whatever its economic potential, seldom offers more than “conservation opportunities.”

Rio Tinto did not respond to requests for comment

Rowan Moore Gerety is a writer living in Los Angeles. He was in Madagascar from October-December of 2008. He can be reached at “rowanmg [at] gmail [dot] com”

Related articles

Conservation success in Madagascar proves illusory in crisis

(06/12/2009) Despite the popularity he enjoyed abroad, domestic support for ousted president Marc Ravalomanana eroded rather quickly last February when he went head to head with Andry Rajoelina, the rookie mayor of Madagascar’s capital. Rajoelina rallied disparate opposition groups to the cause and soon toppled the incumbent to become, at his own proclamation, President of the “High Authority of Transition.” For the country as a whole, the results have not been encouraging. The tourism industry has shriveled to a shadow of itself, important donors have suspended non-humanitarian aid, and a power vacuum has set in in remote regions of the island, wreaking havoc on some of its most fragile and prized ecosystems.

Nickle mine in Madagascar may threaten lemurs, undermine conservation efforts

(01/21/2009) One of the world’s largest nickel mines will have adverse impacts on a threatened and biologically-rich forest in Madagascar, say conservationists. The $3.8 billion mining project, operated by Canada’s Sherritt, will tear up 1,300 to 1,700 hectares of primary rainforest that houses nearly 1,400 species of flowering plants, 14 species of lemurs, and more than 100 types of frogs. Many of the species are endemic to the forest. While Sherritt says on its web site that is working to minimize its environmental impact, including moving endangered wildlife, replanting trees, and establishing buffer zones near protected areas, conservationists say that efforts are falling short.