New research reveals hopeful signs that overfished marine ecosystems can recover provided adequate protections.

The two-year study, publish in the journal Science, found that efforts to reduce overfishing are beginning to succeed in five of the ten large marine ecosystems examined, suggesting that “sound management can contribute to the rebuilding of fisheries.”

“Highly managed ecosystems are improving” said co-lead author Ray Hilborn of the University of Washington. “Yet there is still a long way to go: of all fish stocks that we examined sixty-three percent remained below target and still needed to be rebuilt.”

“Across all regions we are still seeing a troubling trend of increasing stock collapse,” added co-lead author Boris Worm of Dalhousie University. “But this paper shows that our oceans are not a lost cause. The encouraging result is that exploitation rate – the ultimate driver of depletion and collapse – is decreasing in half of the ten systems we examined in detail. This means that management in those areas is setting the stage for ecological and economic recovery. It’s only a start – but it gives me hope that we have the ability to bring overfishing under control.”

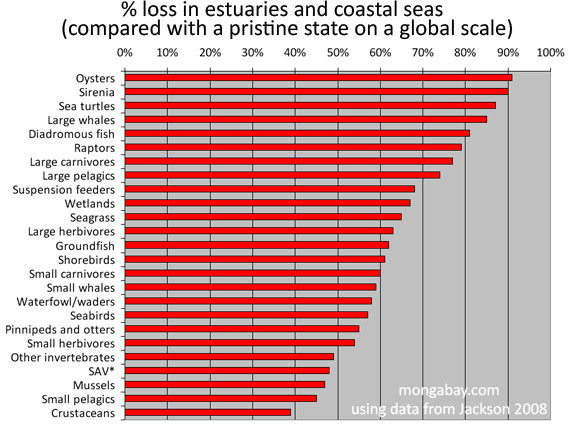

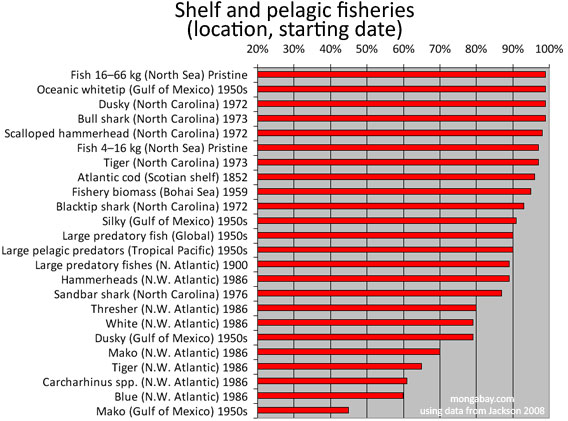

Percent decline (biomass, catch, percent cover) for fauna and flora from various marine environments. Chart based on data from Jeremy Jackson (2008). Ecological extinction and evolution in the brave new ocean. PNAS Online Early Edition for the week of August 11-15, 2008. |

The study focused mostly on intensively managed fisheries in developed countries, where there is solid scientific data on fish abundance, although they find positive signs in some developing countries like Kenya, where marine closures to fishing and restrictions on certain types of fishing gear have lead to an increase in the size and amount of fish available, boosting local incomes.

“These successes are local – but they are inspiring others to follow suit,” said Tim McClanahan of the Wildlife Conservation Society in Kenya.

“We know that more fish can be harvested with less fishing effort and less impact on the environment, if we first slow down and allow overfished populations to rebuild,” said the University of Rhode Island’s Jeremy Collie, one of other 19 co-authors on the study. “Scientists and managers in places as different as Iceland and Kenya have been able to reduce overfishing and rebuild fish populations despite serious challenges.”

The study found that while a range of approaches ̬ including catch quotas, community management, closure to fishing of strategic zones, ocean zoning, restrictions on fishing gear and economic incentives — are useful in rebuilding fish stocks, solutions need to be tailored to local conditions.

Percent decline (biomass, catch, percent cover) for fauna and flora from various marine environments. Chart based on data from Jackson 2008. |

“There are no single silver bullet solutions,” said co-author Beth Fulton of the CSIRO Wealth from Oceans Flagship in Australia. “Management efforts must be customized to the place and the people.”

The best results were seen in areas where controls have been implemented prior to collapse of fisheries. Recovery was particularly marked in Alaska, New Zealand, Iceland, the Northeast U.S. Shelf and the California Current — areas where there is strong management. The researchers didn’t have reliable data for some of the less-governed parts of the world. They caution that some fishing exploitive practices are displaced to countries with weaker laws and enforcement capacity (e.g. off West Africa and the Horn of Africa).

The study also notes that while there are long-term benefits to improved management, there are short-term costs to fishers.

“Some places have chosen to end overfishing,” said Trevor Branch, a co-author from the University of Washington. “That choice can be painful for fishermen in the short term, but in the long term it benefits fish, fishermen, and our ocean ecosystems as a whole.”

|

|

The authors conclude by making a series of recommendations, including fishing at rates lower than those producing maximum sustainable yield (MSY), a long-standing catch target for the fishing industry. Instead the researchers support the U.N.’s suggestion that MSY be “reinterpreted as an absolute upper limit rather than a target.”

“Below MMSY there is a fishing-conservation sweet spot, where economic and ecosystem benefits converge.” said co-author Steven Palumbi of Stanford University.

“Fishing at maximum yield comes at a significant cost of species collapses,” added Heike Lotze, a co-author from Dalhousie University. “But even low levels of fishing do change marine ecosystems and may collapse vulnerable species. That’s why

we require a combination of measures, including gear restrictions and closed areas, in order to meet both fisheries and conservation objectives.”

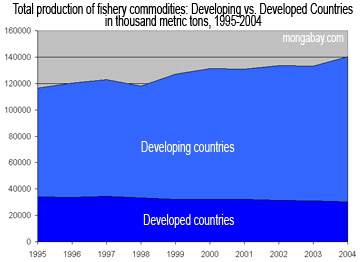

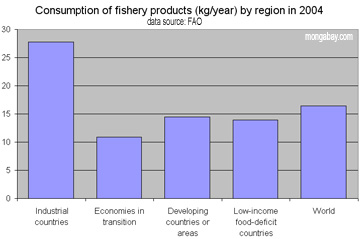

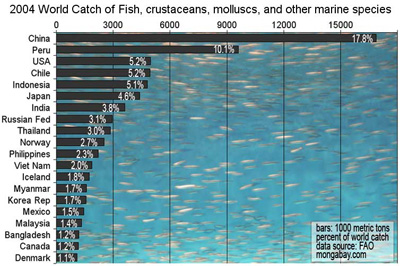

2004 global catch of fish, crustaceans, molluscs, and other marine species, based on FAO data. Chart by R. Butler. |

The authors suggest moving toward a more holistic approach to management, going beyond managing individual species to looking at entire ecosystems and ensuring sustainable livelihoods for poor communities.

“We need to move much more rapidly towards rebuilding individual fish populations and restoring the ecosystems of which they are a part, if there is to be any hope for the long-term viability of fisheries and fishing communities,” said Pamela Mace, a co-author from the New Zealand Ministry of Fisheries.

B. Worm et al. “Rebuilding Global Fisheries.” Science 31 July 2009