Extinction can be set in motion millions of years before a species’ actual demise, suggesting that present-day drivers of habitat destruction and degradation may have already doomed many species to eventual extinction, report researchers writing in Proceedings of the Royal Society B online.

Analyzing the fossil record of microscopic coral-like animals known as cupuladriid bryozoans, Aaron O’Dea of the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute and Jeremy Jackson of Scripps Institution of Oceanography found that extinction of different forms of bryozoans came 1-2 million years after the emergence of the Isthmus of Panama, an event that triggered dramatic environmental changes in the Eastern Pacific and the Caribbean.

Three to four-and-a-half million years ago, the volcanic rise of the Panamanian land bridge between North and South America divided a once great ocean into the Caribbean Sea and Pacific Ocean we know today. The closure of the isthmus blocked the nutrient-replenishing current from the Pacific caused stagnation in the Caribbean, eventually triggering the rise of complex communities including coral reefs and algae where competition over scarce resources was fierce. Meanwhile, the upwelling in the Pacific brought a wealth of nutrients from the depths of the ocean, producing a greater abundance of life but less species richness. Species that couldn’t adapt to the environmental change went extinct, but did so 1-2 million years later.

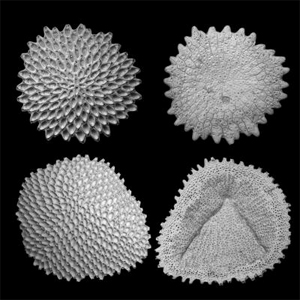

Scanning electron microscope photos of these minutely sculptured cupuladriid bryozoan fossils tell paleontologists whether the animal reproduced sexually or clonally. Top: Sexual form– frontal and basal views Bottom: Clonal form–frontal and basal views. Credit: Aaron O’Dea |

Cupuladriid Bryozoans, which reproduce either by cloning or by sex depending on their environment, were affected by the changes. Nutrient-rich environments tend to favor the cloning strategy, so the closure of the isthmus lead to the eventual extinction of clonal bryozoans. They were replaced with bryozoans that relied on sexual reproduction, a strategy that works better under nutrient-poor conditions.

“As the Caribbean Sea was cut off from the Pacific Ocean, many new species appeared in the fossil record, and all reproduced sexually,” said O’Dea.

Jackson, emeritus staff scientist at the Smithsonian, notes that the findings indicate that extinction can drag out millions of years after an event, a conclusion that has implications for modern-day biodiversity loss.

“It’s important to distinguish between ecological extinction—when these organisms stopped being important players in the game—and actual extinction, when they disappeared from the geological record,” said Jackson. “The idea that extinction may be delayed by millions of years after the cause is worrisome. Today an overwhelming number of species are being reduced in abundance. The forecast from the fossil record is that even if they survive now, the ultimate cause of their extinction may already have passed us by.”

Other researchers estimate the current extinction rate may be 1,000 to 10,000 times the biological norm of 1-10 species extinctions per year. Although great extinctions have occurred in the past, this is the first mass extinction event driven by the actions of a single species.

Extinction, like climate change, is complicated

(03/26/2007) Extinction is a hotly debated, but poorly understood topic in science. The same goes for climate change. When scientists try to forecast the impact of global change on future biodiversity levels, the results are contentious, to say the least. While some argue that species have managed to survive worse climate change in the past and that current threats to biodiversity are overstated, many biologists say the impacts of climate change and resulting shifts in rainfall, temperature, sea levels, ecosystem composition, and food availability will have significant effects on global species richness.

Climate change will cause biomes to shift and disappear

(03/26/2007) Many of the world’s local climates could be radically changed if global warming trends continue, reports a new study published in the early online edition of the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. The authors warn that current climates may shift and disappear, increasing the risk of biodiversity extinction and other ecological changes.

Just how bad is the biodiversity extinction crisis?

(02/06/2007) In recent years, scientists have warned of a looming biodiversity extinction crisis, one that will rival or exceed the five historic mass extinctions that occurred millions of years ago. Unlike these past extinctions, which were variously the result of catastrophic climate change, extraterrestrial collisions, atmospheric poisoning, and hyperactive volcanism, the current extinction event is one of our own making, fueled mainly by habitat destruction and, to a lesser extent, over-exploitation of certain species. While few scientists doubt species extinction is occurring, the degree to which it will occur in the future has long been subject of debate in conservation literature. Looking solely at species loss resulting from tropical deforestation, some researchers have forecast extinction rates as high as 75 percent. Now a new paper, published in Biotropica, argues that the most dire of these projections may be overstated. Using models that show lower rates of forest loss based on slowing population growth and other factors, Joseph Wright from the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute in Panama and Helene Muller-Landau from the University of Minnesota say that species loss may be more moderate than the commonly cited figures. While some scientists have criticized their work as “overly optimistic,” prominent biologists say that their research has ignited an important discussion and raises fundamental questions about future conservation priorities and research efforts. This could ultimately result in more effective strategies for conserving biological diversity, they say.