A 20-year study on rhesus monkeys found that substantially reducing caloric intake slows the aging process and leads to longer lifespans in primates. The research, published in the journal Science, suggests that a reduced-calorie diet could delay the onset of age-related disorders like cancer, diabetes, cardiovascular disease and brain atrophy in humans.

“We have been able to show that caloric restriction can slow the aging process in a primate species,” said Richard Weindruch, a professor of medicine at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. “We observed that caloric restriction reduced the risk of developing an age-related disease by a factor of three and increased survival.”

Previous research has shown that caloric restriction of around 30 percent leads to health benefits in yeast, worms, flies, and rodents, but the new study is the first to demonstrate the effects in a primate over a large sample for an extended period of time. Ricki Colman of the Wisconsin National Primate Research Center and colleagues began their experiment in 1989 by assigning adult rhesus monkeys, each between age seven and 14, to either a caloric restriction group or a control group with unrestricted access to food. Caloric intake was reduced in the dieting group by 30 percent over three months and held at that level for the rest of their lives. By the end of the study, 37 percent of the control group had died of age-related causes while only 13 percent of the dieting group has succumbed to age-related conditions like diabetes, cancer, cardiovascular disease, and brain atrophy. Of the 33 animals remaining in the study, 13 are from the control group and 20 are from the calorie-restricted group.

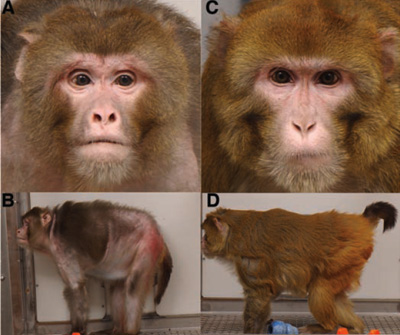

Animal appearance in old age. (A and B) Photographs of a typical control animal at 27.6 years of age (about the average life span). (C and D) Photographs of an age-matched animal on caloric restriction. Photograph courtesy of Science. |

“There is a major effect of caloric restriction in increasing survival if you look at deaths due to the diseases of aging,” said Weindruch. “So far, we’ve seen the complete prevention of diabetes.”

The researchers also found that a reduced-calorie diet also helped brain health.

“It seems to preserve the volume of the brain in some regions,” Sterling Johnson, a neuroscientist in the UW-Madison School of Medicine and Public Health, said. “It’s not a global effect, but the findings are helping us understand if this dietary treatment is having any effect on the loss of neurons” during aging.

“Both motor speed and mental speed slow down with aging. Those are the areas which we found to be better preserved. We can’t yet make the claim that a difference in diet is associated with functional change because those studies are still ongoing. What we know so far is that there are regional differences in brain mass that appear to be related to diet.”

“The atrophy or loss of brain mass known to occur with aging is significantly attenuated in several regions of the brain,” added Weindruch. “That’s a completely new observation.”

The researchers write that while no comprehensive long-term studies have been conducted with human subjects, “given the obvious parallels between rhesus monkeys and humans, the beneficial

effects of caloric restriction may also occur in humans.”

“This prediction is supported by studies of people on long-term caloric restriction, who show fewer signs of cardiovascular aging,” they continue. “The effect of controlled long-term caloric restriction on maximal life span in humans may never be known, but our extended study will eventually provide such data on rhesus monkeys.

R.J. Colman et al. Caloric Restriction Delays Disease Onset and Mortality in Rhesus Monkeys. SCIENCE VOL 325 10 JULY 2009