|

|

The Brazilian soy industry has agreed to extend a moratorium on soy production in newly deforested areas in the Amazon rainforest, reports Greenpeace. The moratorium has been in place since 2006.

Carlos Minc, Brazil’s environmental minister, announced the extension during a press conference in Brasilia.

“Soya is no longer a significant force in the destruction of the Amazon rainforest. However, we cannot say the same about cattle. The soya moratorium is a model for all relevant sectors,” said Brazil’s Environment Minister Carlos Minc.

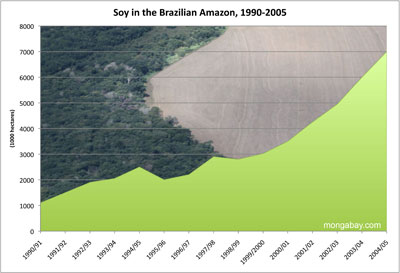

Soy expansion in the Legal Amazon (Amazônia). Enlarge image. Soy’s impact in the Amazon has been less direct than ranching, with lands already cleared for pasture being converted to soy farms. Further, investments to facilitate soy expansion — including road development and ports — have promoted deforestation. |

Cattle ranching is the biggest driver of deforestation in the Brazilian Amazon, accounting for about 80 percent of new clearing, but the industry is now under pressure to follow the lead of soy producers. Already Marfrig, the world’s fourth largest beef trader, has said it will no longer buy beef produced on newly deforested lands, while other buyers are showing interest in an emerging certification scheme that would ensure beef comes from responsibly managed ranches. Certification standards are also being developed for the soy industry.

“We want to ensure that our actions help protect the Amazon rainforest. The moratorium has been a positive step in helping us control and monitor the soya used in our supply chain and we will continue to participate in efforts to stop deforestation in the Amazon,” said Denis Hennequin, McDonald’s Europe president.

The certification system may include some form of ecosystem services payments to encourage landowners to conserve forest on private lands.

“Compensation for environmental services would be a great incentive to the rural producer to stop deforesting. The industry expects that by the end of the year, in Copenhagen, the governments of different countries will commit to put a fund together for forest protection which will include compensation,” said Carlo Lovatelli, President of the Brazilian Association of Vegetable Oils Industries.

Soy moratorium shows success

Soy fields and transition forest in Mato Grosso, Brazil |

A satellite-based study released earlier this year showed that only 12 of 630 sample areas (1,389 of 157,896 hectares) deforested since July 2006 — the date the moratorium took effect — were planted with soy. While the sample was small — covering 157,896 hectares in a region where individual soy farms can extend over thousands of hectares — it provided a hopeful sign that soy producers are abiding by the moratorium, which was established as a response to environmentalists who said that soy was driving Amazon rainforest destruction. Producers feared they would lose access to international markets.

Soy production in the Amazon exploded in the early 1990s following the development of a new variety of soybean suitable to the soils and climate of the region. Most expansion occurred in the cerrado, a wooded grassland ecosystem, and the transition forests in the southern fringes in the Amazon basin, especially in states of Mato Grosso and Pará — direct conversion of rainforests for soy has been relatively limited. Instead, the impact of soy on rainforests is generally seen by environmentalists to be indirect. Soy expansion has driven up land prices, created impetus for infrastructure improvements that promote forest clearing, and displaced cattle ranchers to frontier areas, spurring deforestation.

The Brazilian soy industry argues that it receives an unfair share of the blame for Amazon forest loss. It notes that producers in the legal Amazon face some of the most stringent environmental laws in the world, with landowners required to maintain 80 percent forest cover on their holdings. By comparison there are no legal forest reserve requirements for U.S. farmers.

Greenpeace did not respond the multiple requests for comment.