A Scottish firm has been implicated in funding a plan that would destroy the rainforest habitat of critically endangered orangutans in Sumatra.

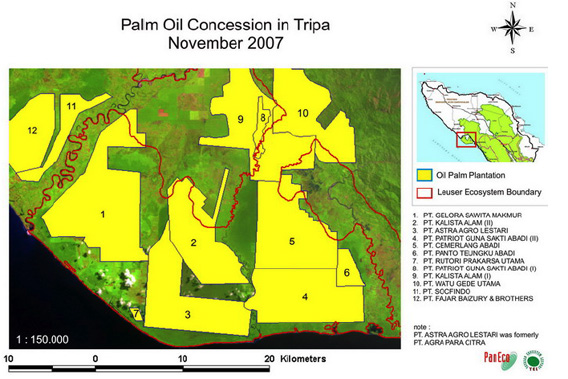

Jardine Matheson Holdings is the majority shareholder of Astra Agro Lestar, a palm oil company that plans to develop the peatland forests of Tripa in Aceh Province for oil palm plantations. Environmentalists say conversion of the forest would destroy a biologically rich ecosystem that serves as a buffer against natural disasters in a region that bore the brunt of the 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami that killed more than 225,000 people. Draining of the carbon-dense peat soils would also accelerate climate change by releasing vast amounts of CO2 into the atmosphere.

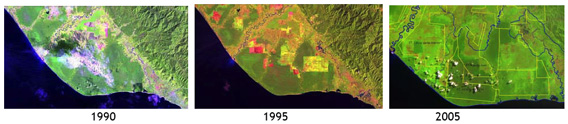

Images showing oil palm plantation concessions and forest cover change from 1990 to 2005 in Tripa. Courtesy of YEL/PanEco Foundation |

In a series of statements, members of the coalition blasted Jardine and its chairman Sir Henry Keswick, who was knighted this month in the Queen’s birthday honors list.

“It’s scandalous that a British company is bankrolling the destruction of this vital part of Indonesian rainforest,” said Greenpeace forest campaigner James Turner. “If the executives at Jardines don’t stop this they will be rightly accused of speeding up climate change, destroying a vital tsunami buffer zone and driving the Sumatran orangutan to the brink of extinction.”

“It is frankly shocking that the Chairman of Jardine Matheson has been knighted for services to British business interests overseas, while his company is actively contributing to the demise of the critically endangered Sumatran orangutan,” said Helen Buckland, UK Director, Sumatran Orangutan Society (SOS). “British businesses must be held accountable for their part in the destruction of this globally important area of forest.”

Sumatran orangutan in the Leuser ecosystem in North Sumatra. Photo taken by Rhett A. Butler in May 2009. |

“The crisis facing Tripa Swamp Forest demonstrates just how ruthless this industry can be,” said Michelle Desiliets, Director of the Orangutan Land Trust. “A UK-based company, chaired by an individual recently knighted for services to British business interests overseas and charitable activities in the UK, provides the investment for such destruction, and as such, surely cannot claim to have any interest in Corporate Social Responsibility.”

Orangutan refuge

Twenty years ago Tripa was home to around 1,500 orangutans but hunting and habitat destruction have reduced the population to around 280, or about 4 percent of the 6,600 Sumatran orangutans that remain in the wild.

Trip is one of Sumatra’s few remnant lowland forests. Since 1975, the extent of primary forest cover in Sumatra has decreased by more than 90 percent due to logging, agricultural expansion, and plantation forestry — especially rubber and oil palm.

“This case in unfortunately just one example,” said Alex Kaat from Wetlands International. “Throughout Indonesia and Malaysia, we see that the last remaining peatswamp forests are cleared for palm oil production to meet the growing demands for vegetable oils and biofuels.”

Deforestation in another part of the Leuser ecosystem, on the border of Gunung Leuser National Park. A field assessment in November 2007 by YEL/PanEco Foundation, the World Agroforestry Centre (ICRAF) and UNSYIAH (University of Syiah Kuala, Banda Aceh), found total above ground carbon stock in the remaining 31,410 hectares (77,550 acres) of forest in Tripa to be around 4 million tons. Below ground carbon stocks were estimated to be at least five times that figure. |

While the oil palm is the world’s most productive oilseed — far outstripping canola or soy — conversion of forests and peatlands for its cultivation has sparked alarm among environmental groups concerned by its impacts on biodiversity and climate. The worries have been supported by a series of studies published since 2007 in peer-reviewed scientific journals showing that biodiesel produced from palm oil grown at the expense of these ecosystems is worse for the planet than conventional fuels. In response, some industry members say they will avoid developing high conservation value forests and peatlands for new plantations, instead focusing on degraded grasslands and improving yields on existing plantations. The Indonesian government has also restricted development of peatlands deeper than 10 feet (3 meters) for oil palm. Still some firms continue to develop contentious parcels, sometimes in direct conflict with local communities.