A new paper by Oscar Venter, a PhD student at the University of Queensland, and colleagues finds that forest conservation via REDD — a proposed mechanism for compensating developing countries for Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Degradation — could be economically competitive with oil palm production, a dominant driver of deforestation in Indonesia. The study is published online in the journal Conservation Letters.

The study, based on overlaying maps of proposed oil palm development with maps showing carbon-density and wildlife distribution in Kalimantan (Indonesian Borneo), estimates that REDD is financially competitive, and potentially able to fund forest conservation, relative to oil palm at carbon prices of $10-$33 per ton of carbon dioxide equivalent (tCO2e). In areas with low agricultural suitability and high carbon density, notably peatlands, Venter and colleagues find that a carbon price of $2 per tCO2e would be sufficient to beat out returns from oil palm.

Orangutan in Kalimantan |

The study also revealed that 40 of Kalimantan’s 46 globally threatened mammals, including the orangutan and Bornean elephant, are found within areas slated for oil palm development, suggesting that REDD could be a critical source of funding for biodiversity conservation.

“Most importantly, we discover that areas where emissions reductions are cheapest contain twice the average levels of endangered mammals, demonstrating that REDD has the potential to deliver win-wins for carbon and biodiversity objectives,” Venter wrote via email.

The study’s most hopeful results — instances where the break-even point for REDD and palm oil is a low carbon price — are based partly on the premise that below ground biomass found in peatlands will be compensated under a future REDD framework. In recent months momentum for the inclusion of emissions from peatlands has been building, largely due to the recognition that such emissions are substantial — up to 8 percent of global emissions in some years.

Draining and clearing of peat forest in Central Kalimantan. Photo by Rhett A. Butler. |

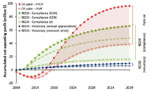

The results therefore differ somewhat from those presented my Lian Pin Koh, Jaboury Ghazoul, and myself in a paper [PDF] published earlier this year in the same journal. We operated on the conservative assumption that only above ground biomass would be compensated. Adjusting (using our freely accessible online model [xls]) for the inclusion of some below ground biomasss from peatlands (450 tons of total carbon per hectare, slightly less than Venter et al.), our model suggests a breakeven price of $5-15/tCo2e for a front-weighted allocation system (where carbon credits are allocated as deforestation occurs) and $11-30/tCo2e for an equal-weighted allocation system (where are carbon credits are distributed evenly over a 30-year period).

Oscar Venter et al. Carbon payments as a safeguard for threatened tropical mammals. Conservation Letters xx (2009) 1–7 doi: 10.1111/j.1755-263X.2009.00059.x

Related articles

Can carbon credits from REDD compete with palm oil?

(03/30/2009) Reducing emissions from deforestation and degradation (REDD) is increasingly seen as a compelling way to conserve tropical forests while simultaneously helping mitigate climate change, preserving biodiversity, and providing sustainable livelihoods for rural people. But to become a reality REDD still faces a number of challenges, not least of which is economic competition from other forms of land use. In Indonesia and Malaysia, the biggest competitor is likely oil palm, which is presently one of the most profitable forms of land use. Oil palm is also spreading to other tropical forest areas including the Brazilian Amazon.

Could peatlands conservation be more profitable than palm oil?

(08/22/2007) This past June, World Bank published a report warning that climate change presents serious risks to Indonesia, including the possibility of losing 2,000 islands as sea levels rise. While this scenario is dire, proposed mechanisms for addressing climate change, notably carbon credits through avoided deforestation, offer a unique opportunity for Indonesia to strengthen its economy while demonstrating worldwide innovative political and environmental leadership. In a July 29th editorial we argued that in some cases, preserving ecosystems for carbon credits could be more valuable than conversion for oil palm plantations, providing higher tax revenue for the Indonesian treasury while at the same time offering attractive economic returns for investors.