A new study finds Amazon deforestation fails to sustain long-term economic growth for rural populations. The findings come as development interests in Brazil push for government support to bolster infrastructure projects and agricultural expansion in the world’s largest rainforest.

Deforestation generates short-term benefits but fails to increase affluence and quality of life in the long-run, reports a new study based an analysis of forest clearing in 286 municipalities across the Brazilian Amazon. The research, published in Friday’s issue of the journal Science, casts doubt on the argument that deforestation is a critical step towards development and suggests that mechanisms to compensate communities for keeping forests standing may be a better approach to improving human welfare, while simultaneously sustaining biodiversity and ecosystem services, in rainforest areas.

Rainforest and soy in the Brazilian Amazon. |

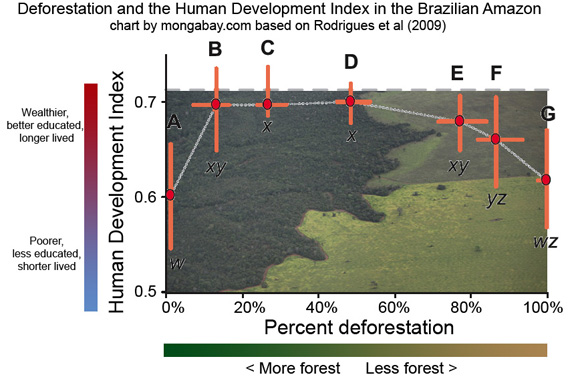

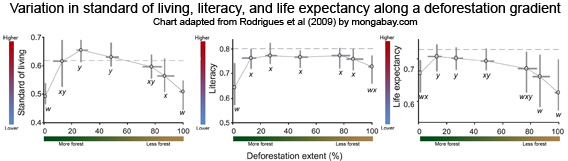

To reach this conclusion, Ana Rodrigues, a researcher formerly with University of Cambridge and currently at the Centre of Functional and Evolutionary Ecology in France, and colleagues used the United Nations Development Program’s Human Development Index, a metric that combines life expectancy, literacy, and standard of living, to assess the welfare of 286 municipalities with varying degrees of deforestation. They found that relative welfare increases as deforestation begins, but then declines as the frontier progresses on to other areas, leaving pre- and post-deforestation levels of human development statistically equal. In other words, the boom-and-bust cycle generates few lasting benefits for local permanent populations. Most gains accrue to a population of migrants — loggers, ranchers, speculators, land squatters, miners, and farmers — that move with the frontier as resources are exhausted and land is degraded.

“The Amazon is globally recognized for its unparalleled natural value, but it is also a very poor region. It is generally assumed that replacing the forest with crops and pastureland is the best approach for fulfilling the region’s legitimate aspirations to development,” Rodrigues explained. “This study tested that assumption. We found although the deforestation frontier does bring initial improvements in income, life expectancy, and literacy, such gains are not sustained.”

“The ‘boom’ in development that deforestation brings to these areas is clear, but our data show that in the long run these benefits are not sustained. Along with environmental concerns, this is another good reason to restrict further deforestation in the Amazon,” added co-author Rob Ewers from Imperial College London. “However, in areas that are currently being deforested, the process needs to be better managed to ensure that for local people boom isn’t necessarily followed by ‘bust’.”

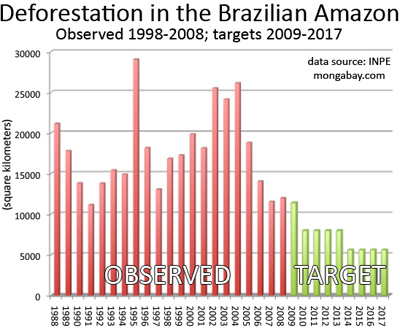

But slowing deforestation is will not be easy. Those who benefit most from short-term exploitation — large-scale ranchers, industrial logging, agricultural giants, and absentee land barons — have considerable political clout in Brazil and have lately been pushing measures that will drive more Amazon deforestation, including a bill (HB 458) passed by the Senate last week that will grant legal title to 600,000 square kilometers of illegally occupied Amazon rainforest land. The bill favors industrial developers over small landholders, allowing those controlling 400-1500 ha to sell their holdings after three years, but requiring farmers with smaller plots to wait 10 years to sell. Brazil has also committed to spend upwards of $40 billion on new infrastructure projects — including dams, ports, and road improvement — in the Amazon to support development in the region.

For all their promise, payments-for-ecosystem-services schemes will only be effective where there is the institutional capacity to deliver benefits to local people. Presently, the lack of the governance in frontier regions is a hindrance to slowing deforestation. But this may be is changing. While critics says HB 458 favors big industry and may drive new deforestation, the bill will “regularize” land holdings, potentially improving land tenure systems. |

While this political pressure remains a challenge, the authors suggest a solution may lie in a multifaceted approach that includes both boosting returns on already deforested lands and limiting further deforestation.

“A combined approach might include supporting the better use of areas that have already been deforested (e.g., via the intensification of ranching and agriculture) alongside restricting further deforestation [e.g., through protected areas and appropriate land use zoning] and promoting reforestation in degraded landscapes; direct incentives to encourage forest-based livelihoods based on the sustainable harvest of timber and nontimber forest products, within and beyond forest concessions; and targeted policies to improve literacy, health, and land tenure security,” they write.

The authors argue that emerging payments-for-ecosystem-services schemes could become a key mechanism for delivering benefits to local populations as an incentive for preserving forests as viable and productive ecosystems. A handful of ecosystem services programs are already being implemented in the Brazilian Amazon, including Bolsa Floresta in the state of Amazonas, an initiative that offers payment and access to education and healthcare to families that voluntary agree to reduce deforestation. Such programs would benefit from a proposed climate change mitigation mechanism, known as reducing emissions from deforestation and degradation (REDD), currently under discussion for the next international climate treaty, which will be hammered out this December at the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change in Copenhagen. REDD would pay tropical countries to keep their forests standing.

Click image to enlarge Since 2003 Brazil has set aside 523,592 square kilometers of protected areas, accounting for 74 percent of the total land area protected worldwide during that period. |

“New financial mechanisms and policies are paving the way for more sustained development trajectories and creating the conditions in which the largest tropical forest in the world can be recognized as more valuable standing than felled,” the authors conclude.

Brazil houses more than 60 percent of the Amazon rainforest, the world’s largest tropical forest. Over the past 30 years nearly one-fifth of the forest area have been cleared, largely for agriculture and cattle pasture. Scientists estimate the forest may be home to one quarter of the world’s land-based plant and animal species as well as the largest population of indigenous people still living in traditional ways. Some researchers fear that continued clearing, together with increased incidence and severity of drought and fire due to climate change, could result in a large scale die-off of the Amazon by the end of the century.

Citation: Ana S. L. Rodrigues, Robert M. Ewers, Luke Parry, Carlos Souza Jr., Adalberto Veríssimo,6 Andrew Balmford1. Boom-and-Bust Development Patterns Across the Amazon Deforestation Frontier. SCIENCE VOL 324 12 JUNE 2009

Related articles

Brazil’s plan to save the Amazon rainforest

(06/02/2009) Accounting for roughly half of tropical deforestation between 2000 and 2005, Brazil is the most important supply-side player when it comes to developing a climate framework that includes reducing emissions from deforestation and forest degradation (REDD). But Brazil’s position on REDD contrasts with proposals put forth by other tropical forest countries, including the Coalition for Rainforest Nations, a negotiating block of 15 countries. Instead of advocating a market-based approach to REDD, where credits generated from forest conservation would be traded between countries, Brazil is calling for a giant fund financed with donations from industrialized nations. Contributors would not be eligible for carbon credits that could be used to meet emission reduction obligations under a binding climate treaty.

(04/15/2009) An industry-led moratorium on soy plantings on recently deforested rainforest land continues to show success in the Brazilian Amazon, reports a study released Tuesday by environmental groups and Abiove, the soy industry group that formed the initiative and represents about 90 percent of Brazil’s soy crush. The satellite-based study showed that only 12 of 630 sample areas (1,389 of 157,896 hectares) deforested since July 2006 — the date the moratorium took effect — were planted with soy.

37,000 sq km of Amazon rainforest destroyed or damaged in 2008

(03/19/2009) Logging and fires damaged nearly 25,000 square kilometers (9,650 square miles) of Amazon rainforest in the August 2007-July 2008 period, an increase of 67 percent over the prior year period, according to a new mapping system developed by Brazil’s National Institute for Space Research (INPE). The damage comes on top of the nearly 12,000 sq km (4,600 sq mi) of rainforest that was cleared during the year.