|

|

Brazil’s setting aside of more than 500,000 square miles (1.25 million square kilometers) of rainforest in protected areas over the past decade may effectively buffer the Amazon from the effects of climate change, preventing Earth’s largest rainforest from tipping towards arid savanna in the face of ongoing deforestation and rising temperatures, argues a new paper published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS).

The conclusion is based on the application of a regional climate model, run on the assumption that all land not currently under some form of protection would be deforested across the Brazilian Amazon. Roughly 37 percent of the region is presently protected in indigenous territories and state and government reserves, while around 17 percent has already been cleared, leaving about 45 percent of the Amazon still up-for-grabs.

Since 2003 Brazil has set aside 523,592 square kilometers of protected areas, accounting for 74 percent of the total land area protected worldwide during that period. |

The study, led by Robert Walker, a professor of geography at Michigan State University, looked specifically at the impact of forest conversion on regional rainfall. It found that Brazil’s protection of a core zone of rainforest would be enough to maintain precipitation across the basin and avoid the catastrophic “die-off” projected by other models, notably the Hadley model produced by the UK Meteorological Office.

“The thought has been that if you deforest up to a certain point in the Amazon, the forest will completely lose the ability to recover its tropical vegetation – that you will basically convert it to a desert, especially in the south and southeastern margins of the basin,” said Walker.

“But our research shows that if you protect certain areas of the Amazon, as the Brazilian government is currently doing, the forest will not reach a tipping point, which means we can maintain the climate with levels of deforestation beyond which was originally thought.”

Walker says the results suggest the Amazon could lose up to 60 percent of its forest cover without reaching the tipping point where rainforest gives way to savanna.

“Some people think the tipping point is going to occur at 30 percent to 40 percent deforestation,” Walker said. “Our results suggest this is not the case; that you can have quite a bit of deforestation – perhaps up to 60 percent – before you get to the crash point.”

But the study rests on the “optimistic assumption that the protected areas remain largely preserved.” Some protected areas in Brazil have already been degraded by fires that escape from adjacent agricultural areas or completely deforested by developers.

Still the authors are hopeful that other measures will maintain forest cover outside protected areas. These include Brazil’s forest code, which requires Amazon landholders to keep 50-80 percent of their land forested, and a proposed climate change mitigation mechanism, known as internationally as REDD, that would compensate land owners for keeping their forests standing.

But while the authors seem confident that Brazil’s existing protected areas will be enough to stave off large-scale drying in the Amazon, a number of other recently published papers (see “related articles” below) suggest a less rosy outlook. The PNAS paper seems to downplay the effects of climate change, which drove a severe drought in 2005 that stranded river boats, isolated communities, and contributed to massive forest fires across the Amazon. Further the rainfall measurements used in the study were based an average from 1997-2001, which effectively excludes variability seen in recent drying episodes.

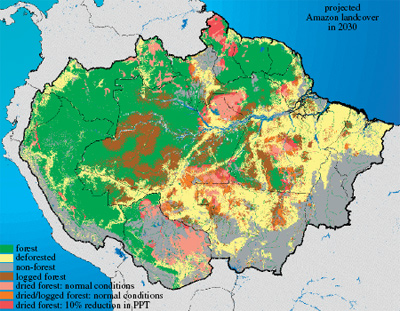

An alternative forecast from Nepstad et al (2008) projects this map of Amazonia for 2030, showing drought-damaged, logged and cleared forests. Nepstad’s model assumes the last 10 years of climate are repeated in the future. |

“This is an interesting analysis but we believe it underplays the importance of the Amazon hydrological cycle in part by not taking annual variation into account,” said Thomas Lovejoy of the H. John Heinz Center for Science. “Further the reality is that climate change is not included in this analysis and in the real world will be synergistic with deforestation and fire. A forthcoming World Bank study will illuminate the importance of synergies.”

“Furthermore, recent studies suggest that fragmenting the Amazon forest could disrupt regional rainfall by breaking down a ‘biotic pump’, in which evapotranspiration from forests creates low-pressure zones that draw in moisture-laden air from the Atlantic Ocean,” said William F. Laurance, a researcher at the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute, who together with Lovejoy, won the 2009 BBVA Foundation Frontiers of Knowledge Award in Ecology and Conservation Biology for their work in the Brazilian Amazon. “If this mechanism is as important as some analyses suggest, Amazon rainfall could decline abruptly if forests are further cleared and fragmented.”

Of course protecting the Amazon rainforest offers other benefits beyond maintenance of regional rainfall and vegetation cover. The region locks up more than 100 billion tons of carbon — more than 11 years’ worth of total greenhouse gas emissions from human activities; plays an important role in global weather circulation patterns, including delivering rainfall to Central America, the United States, and southern South America; supports perhaps a third of terrestrial biodiversity; and is home to the bulk of the world’s remaining indigenous people still living in traditional ways.

CITATION: R.A. Walker. Protecting the Amazon with protected areas. PNAS Early Edition for the week of June 15, 2009.

Abstract: This article addresses climate-tipping points in the Amazon Basin resulting from deforestation. It applies a regional climate model to assess whether the system of protected areas in Brazil is able to avoid such tipping points, with massive conversion to semiarid

vegetation, particularly along the south and southeastern margins of the basin. The regional climate model produces spatially distributed

annual rainfall under a variety of external forcing conditions, assuming that all land outside protected areas is deforested. It translates these results into dry season impacts on resident ecosystems and shows that Amazonian dry ecosystems in the southern and southeastern basin do not desiccate appreciably and that extensive areas experience an increase in precipitation. Nor do the moist forests dry out to an excessive amount. Evidently, Brazilian environmental policy has created a sustainable core of protected areas in the Amazon that buffers against potential climate-tipping points and protects the drier ecosystems of the basin. Thus, all efforts should be made to manage them effectively

Related articles

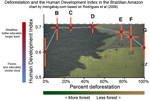

Amazon deforestation doesn’t make communities richer, better educated, or healthier

(06/11/2009) Deforestation generates short-term benefits but fails to increase affluence and quality of life in the long-run, reports a new study based an analysis of forest clearing in 286 municipalities across the Brazilian Amazon. The research, published in Friday’s issue of the journal Science, casts doubt on the argument that deforestation is a critical step towards development and suggests that mechanisms to compensate communities for keeping forests standing may be a better approach to improving human welfare, while simultaneously sustaining biodiversity and ecosystem services, in rainforest areas.

Brazil’s plan to save the Amazon rainforest

(06/02/2009) Accounting for roughly half of tropical deforestation between 2000 and 2005, Brazil is the most important supply-side player when it comes to developing a climate framework that includes reducing emissions from deforestation and forest degradation (REDD). But Brazil’s position on REDD contrasts with proposals put forth by other tropical forest countries, including the Coalition for Rainforest Nations, a negotiating block of 15 countries. Instead of advocating a market-based approach to REDD, where credits generated from forest conservation would be traded between countries, Brazil is calling for a giant fund financed with donations from industrialized nations. Contributors would not be eligible for carbon credits that could be used to meet emission reduction obligations under a binding climate treaty.

Revolutionary new theory overturns modern meteorology with claim that forests move rain

(04/01/2009) Two Russian scientists, Victor Gorshkov and Anastassia Makarieva of the St. Petersburg Nuclear Physics, have published a revolutionary theory that turns modern meteorology on its head, positing that forests—and their capacity for condensation—are actually the main driver of winds rather than temperature. While this model has widespread implications for numerous sciences, none of them are larger than the importance of conserving forests, which are shown to be crucial to ‘pumping’ precipitation from one place to another. The theory explains, among other mysteries, why deforestation around coastal regions tends to lead to drying in the interior.

Amazonian region likely to become savannah due to burning, deforestation

(03/31/2009) A new analysis shows that the heavily-deforested Amazonian region of Mato Grosso is particularly susceptible to ‘savannization’ due to repeated burning that has likely depleted the region’s soils of precious nutrients. According to the study, published in the Journal of Geophyscial Research, savannization, or the process of tropical ecosystems shifting to savannah, is likely in northern Mato Grosso even if no further deforestation occurs.

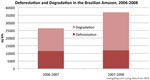

37,000 sq km of Amazon rainforest destroyed or damaged in 2008

(03/19/2009) Logging and fires damaged nearly 25,000 square kilometers (9,650 square miles) of Amazon rainforest in the August 2007-July 2008 period, an increase of 67 percent over the prior year period, according to a new mapping system developed by Brazil’s National Institute for Space Research (INPE). The damage comes on top of the nearly 12,000 sq km (4,600 sq mi) of rainforest that was cleared during the year.

Half the Amazon rainforest will be lost within 20 years

(02/27/2008) More than half the Amazon rainforest will be damaged or destroyed within 20 years if deforestation, forest fires, and climate trends continue apace, warns a study published in Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B. Reviewing recent trends in economic, ecological and climatic processes in Amazonia, Daniel Nepstad and colleagues forecast that 55 percent of Amazon forests will be “cleared, logged, damaged by drought, or burned” in the next 20 years. The damage will release 15-26 billion tons of carbon into the atmosphere, adding to a feedback cycle that will worsen both warming and forest degradation in the region. While the projections are bleak, the authors are hopeful that emerging trends could reduce the likelihood of a near-term die-back. These include the growing concern in commodity markets on the environmental performance of ranchers and farmers; greater investment in fire control mechanisms among owners of fire-sensitive investments; emergence of a carbon market for forest-based offsets; and the establishment of protected areas in regions where development is fast-expanding.

Deforestation a greater threat to the Amazon than global warming

(02/25/2008) If past conditions are any indication of future conditions, the Amazon rainforest may survive considerable drying and warming caused by global warming, argue researchers in a paper published in Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B.

Global warming could cause catastrophic die-off of Amazon rainforest by 2080

(10/23/2006) For the Amazon, there is an immense threat looming on the horizon: climate change could well cause most of the Amazon rainforest to disappear by the end of the century. Dr. Philip Fearnside, a Research Professor at the National Institute for Research in the Amazon in Manaus, Brazil and one of the most cited scientists on the subject of climate change, understands the threat well. Having spent more than 30 years in Brazil and now recognized as one of the world’s foremost experts on the Amazon rainforest, Fearnside is working to do nothing less than to save this remarkable ecosystem. Fearnside believes saving the Amazon will require a fundamental shift in perception where the Amazon is recognized as an asset beyond the current price of mahogany, soybeans, or cattle, where its value is only unlocked by its destruction. The Amazon is far worth more than this he says. It can play a key role in fighting climate change while providing economic sustenance for millions through sustainable agriculture and rational utilization of its renewable products. It can serve as a storehouse for biodiversity while at the same time ensuring reliable water supplies and moderating regional temperature and precipitation. In short, maintaining the Amazon as a viable ecosystem makes sense economically and ecologically — it is in our best interest to preserve this resource while we still can.