Brazil moved a step closer to approving a controversial law that would grant land title to 300,000 properties illegally established across some 600,000 square kilometers (230,000 square miles) of protected Amazon forest, reports AFP. The move may improve governance in otherwise lawless areas, but could carry a steep environmental cost without safeguards.

Under the bill, which passed Brazil’s Chamber of Deputies Thursday and is now headed to the Senate, a claimant could gain title for properties up to 1,500 hectares (3,700 acres) provided the land was occupied before December 2004. Environmentalists fear the legislation could spark deforestation if it fails to include environmental provisions.

“Without environmental guarantees, the message we would be sending the world is that we are giving land titles away with one hand and a chainsaw with the other,” Environment Minister Carlos Minc was quoted as saying by AFP. “It would be a license to deforest.”

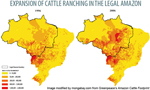

Over the past decade more than 10 million hectares – an area about the size of Iceland – was cleared for cattle ranching as Brazil rose to become the world’s largest exporter of beef. Now the government aims to double the country’s share of the beef export market to 60% by 2018 through low interest loans, infrastructure expansion, and other incentives for producers. Most of this expansion is expected to occur in the Amazon were land is cheap and available. 70 percent of the country’s herd expansion between 2002 and 2006 occurred in the region. |

Development interests have lobbied intensely to strip environmental protections from the current version of the bill, but a coalition of green groups is pressuring lawmakers to include some provisions — including a reforestation requirement — in the version that goes to the Senate. While regularization would effectively legitimize land-grabbing prior to 2004, Minc said the move would help improve enforcement of environmental laws.

“When there are 300,000 people occupying land irregularly, there is no one to fine and make responsible if they don’t respect environmental legislation.”

Land-grabbing has been a major source of social conflict in the so-called Arc of Deforestation, the frontier where most forest clearing is occurring in the Amazon. Typically land invasions are financed by developers seeking to expand holdings, convert forest for cattle pasture, or capitalize on fast-appreciating land prices (cleared land is worth substantially more than forest). Squatters — often transmigrants from the poor northeastern part of the country — are paid to occupy the land until it can be developed by well-capitalized entities registered in under another name. Private (legal forest reserves) and public lands are targeted.

Related

Beef consumption fuels rainforest destruction

(02/16/2009) Nearly 80 percent of deforestation in the Brazilian Amazon results from cattle ranching, according to a new report by Greenpeace. The finding confirms what Amazon researchers have long known – that Brazil’s rise to become the world’s largest exporter of beef has come at the expense of Earth’s biggest rainforest. More than 38,600 square miles has been cleared for pasture since 1996, bringing the total area occupied by cattle ranches in the Brazilian Amazon to 214,000 square miles, an area larger than France. The legal Amazon, an region consisting of rainforests and a biologically-rich grassland known as cerrado, is now home to more than 80 million head of cattle. For comparison, the entire U.S. herd was 96 million in 2008.

How to save the Amazon rainforest

(01/04/2009) Environmentalists have long voiced concern over the vanishing Amazon rainforest, but they haven’t been particularly effective at slowing forest loss. In fact, despite the hundreds of millions of dollars in donor funds that have flowed into the region since 2000 and the establishment of more than 100 million hectares of protected areas since 2002, average annual deforestation rates have increased since the 1990s, peaking at 73,785 square kilometers (28,488 square miles) of forest loss between 2002 and 2004. With land prices fast appreciating, cattle ranching and industrial soy farms expanding, and billions of dollars’ worth of new infrastructure projects in the works, development pressure on the Amazon is expected to accelerate. Given these trends, it is apparent that conservation efforts alone will not determine the fate of the Amazon or other rainforests. Some argue that market measures, which value forests for the ecosystem services they provide as well as reward developers for environmental performance, will be the key to saving the Amazon from large-scale destruction. In the end it may be the very markets currently driving deforestation that save forests.