Yesterday the Obama Administration established a Biofuels Interagency Working Group to oversee implementation of new rules and research regarding biofuels. On the group’s first day they would do well to look at a new study in Science Magazine comparing the efficacy of ethanol versus bioelectricity.

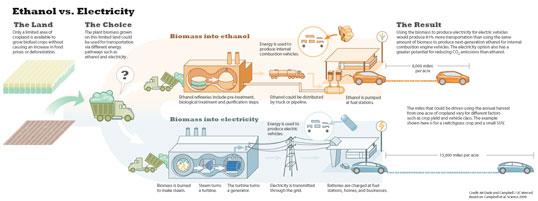

Researchers compared ethanol and bioelectricity in terms of miles per acre of cropland and greenhouse gas emission offsets. Ethanol is a biomass—such as corn or switchgrass—converted into alcohol that can power an internal combustion engine. Bioelectricity, on the other hand, converts similar biomasses into electricity to power a vehicle run on an electric battery.

“It’s a relatively obvious question once you ask it, but nobody had really asked it before,” says study co-author Chris Field, director of the Department of Global Ecology at the Carnegie Institution. “The kinds of motivations that have driven people to think about developing ethanol as a vehicle fuel have been somewhat different from those that have been motivating people to think about battery electric vehicles, but the overlap is in the area of maximizing efficiency and minimizing adverse impacts on climate.”

Field and lead author Elliot Campbell of the University of California, Merced, along with David Lobell of Stanford’s Program on Food Security and the Environment found in a round of tests that bioelectricity beat ethanol no matter the parameters.

On average bioelectricity bested ethanol by 81 percent in terms of miles per acre of cropland and offset 108 percent more greenhouse gas emissions.

The researchers found that in terms of land use it didn’t matter if the energy was produced from corn or switchgrass, bioelectricity clearly won. A small SUV could go nearly 14,000 miles on an acre of switchgrass converted into bioelectricity, whereas the same acre converted into ethanol ran the vehicle 9,000 miles.

“The internal combustion engine just isn’t very efficient, especially when compared to electric vehicles,” says Elliot Campbell. “Even the best ethanol-producing technologies with hybrid vehicles aren’t enough to overcome this.”

The effect on the climate also favored bioelectricity. An acre of switchgrass powering an electric vehicle offset up to 10 tons of CO2 compared to a gasoline-powered car. The offset proved twice as large for bioelectricity as for ethanol. In addition, bioelectricity has more potential for using carbon capture technology, which would offset even more CO2.

“Some approaches to bioenergy can make climate change worse, but other limited approaches can help fight climate change,” explains Campbell. “For these beneficial approaches, we could do more to fight climate change by making electricity than making ethanol.”

While the winner between ethanol and bioelectricity is clear in terms of land use and greenhouse gas emissions, the researchers caution that government and society must take into account additional information.

“Converting biomass to electricity rather than ethanol makes the most sense for two policy-relevant issues: transportation and climate,” says Lobell. “But we also need to compare these options for other issues like water consumption, air pollution, and economic costs.”

CITATION: J. E. Campbell, D. B. Lobell, C.B. Field (2009). Greater Transportation Energy and GHG Offsets from Bioelectricity Than Ethanol. Science Magazine, May 7, 2009.

Related articles

Cellulosic ethanol healthier, better for the environment, than corn ethanol

(02/03/2009) Ethanol produced from switchgrass, prairie biomass, and Miscanthus will reduce the environmental and health impacts of expanded biofuels production relative to using corn as a feedstock, report researchers writing in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Air travel may be powered by biofuels in 3-5 years

(10/27/2008) Boeing says biofuel-powered planes are only three-to-five years away from being a reality, reports The Guardian.

Cellulosic biofuels endanger old-growth forests in the southern U.S.

(10/16/2008) Cellulosic biofuel is on its way. This second generation biofuel so-called because it does not involve food crops has excited many researchers and policymakers who hope for a sustainable energy source that lowers carbon emissions. However, some believe that cellulosic biofuel may prove less-than-perfect. Just as agricultural biofuels have gone from being considered green to an environmental disaster, some think the new rush to cellulosic biofuel will follow the same course. Scot Quaranda is one of those concerned about cellulosic biofuel’s impact on the environment. Campaign director at Dogwood Alliance, which he describes as “the only organization in the Southern US holding corporations accountable for the impact of their industrial forestry practices on our forests and our communities” Quaranda condemns cellulosic biofuels as dangerous to forests “by its very definition”.