|

|

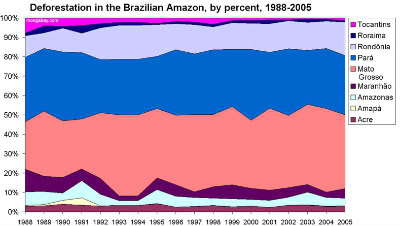

A new analysis shows that the heavily-deforested Amazonian region of Mato Grosso is particularly susceptible to ‘savannization’ due to repeated burning that has likely depleted the region’s soils of precious nutrients. According to the study, published in the Journal of Geophyscial Research, savannization, or the process of tropical ecosystems shifting to savannah, is likely in northern Mato Grosso even if no further deforestation occurs.

Dr. Marcos Costa, one of the study’s authors, describes the savannization tipping point in an ecosystem as such: “the coupled atmosphere-biosphere system would shift from the present rainy climate-rainforest situation to an alternate drier-savanna situation…It involves the coupled vegetation-atmosphere-ocean system, but the evolution of this system apparently depends on other feedbacks that are usually neglected. These feedbacks are associated with the deforestation and agricultural practices, like soil nutrient limitation and fires.”

Aerial view of slash-and-burn agriculture in the Amazon. Photo by: Rhett A. Butler. |

These feedback systems, soil nutrients and fires, are particularly important to an area like Mato Grosso, where large-scale burning has been used for decades by settlers seeking more land for ranching and agriculture. The repeated burning causes a direct loss of soil nutrients in the ecosystem.

“Frequent fires volatilizes significant stocks of [nitrogen], provoking a co-limitation of this nutrient in forests recovering from repeated fire,” the authors write. “Nutrients in the remaining ash might be lost by ash transport, and leaching to surface and groundwater.”

The authors point to previous study which showed that tropical forests suffering from repeated burning—five or more times—“accumulate biomass at an average rate lower than 50% of forests that burned only once, and are more susceptible to further burning.”

Why is the loss of soil nutrients through burning important? “Any plant must capture nutrients from the soil to grow,” explains Costa. “If soil nutrients are depleted, trees grow at a slower rate, because they can’t use efficiently the light and water available.”

Highlighted in pink the tropical forests of Mato Grosso have long suffered largescale deforestation and degradation. |

This loss of nutrients can gradually change ecosystems. If plants are unable to grow quickly and abundantly, rainfall will decrease—due to the fact that precipitation is proportional to deforestation and plant biomass—changing an area that was once rainforest into savannah.

Another factor that contributes directly to Mato Grosso’s future is the length of its dry season.

“In present days, northern Mato Grosso climate barely supports the existence of a rainforest,” Costa remarks. “This is because the dry season is very long, almost as long as in the nearby cerrado. Local deforestation may increase the dry season by a few weeks or a month, which may make it more difficult for forests to regrow there.”

The study found that in the future Mato Grosso’s dry season could extend from May to September, whereas currently it usually ends in August, concluding that future savannization would be “mainly

caused by a longer dry season, although this process only starts in the presence of soil nutrient limitations,” the authors write.

Due to combination of this long dry season with low soil nutrients “in a marginal region [such as Mato Grosso] regrowing a rainforest similar to what it used to be is very unlikely,” says Costa. “If the current high deforestation rates and agricultural practices continue in northern Mato Grosso, we may expect an irreversible vegetation change in this region during the next 50 years. The rest of the Amazon is more resilient, but other regions in Amazonia may be at risk as well.”

Costa believes that the great vulnerability of Mato Grosso’s existing tropical forests make them an important target for conservationists, although he notes “this forest does not store as much carbon and does not have as much biodiversity as the more equatorial Amazon forests.”

With continuing pressure for soybean production, ranch land, and biofuels the outlook for Mato Grosso’s forest is increasingly bleak. According to the study: “over northern Mato Grosso, the rainforest does not recover on the timescale of 50 years, no matter how much is deforested.”

Citation: Monica Carneiro Alves Senna, Marcos Heil Costa, and Gabrielle Ferreira Pires. 2009. Vegetation-atmosphere-soil nutrient feedbacks in the Amazon for different deforestation scenarios. Journal of Geophysical Research, Volume 114.

Related articles

Amazon rainforest in big trouble, says UN

(02/19/2009)

Economic development could doom the Amazon warns a comprehensive new report from the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP). The report — titled GEO Amazonia [PDF-21.3MB] — is largely a synthesis of previously published research, drawing upon studies by more than 150 experts in the eight countries that share the Amazon.

Beef consumption fuels rainforest destruction

(02/16/2009)

Nearly 80 percent of deforestation in the Brazilian Amazon results from cattle ranching, according to a new report by Greenpeace. The finding confirms what Amazon researchers have long known – that Brazil’s rise to become the world’s largest exporter of beef has come at the expense of Earth’s biggest rainforest. More than 38,600 square miles has been cleared for pasture since 1996, bringing the total area occupied by cattle ranches in the Brazilian Amazon to 214,000 square miles, an area larger than France. The legal Amazon, an region consisting of rainforests and a biologically-rich grassland known as cerrado, is now home to more than 80 million head of cattle. For comparison, the entire U.S. herd was 96 million in 2008.

Global warming may drive the Amazon rainforest toward seasonal forests rather than savanna

(02/11/2009)

Changes in rainfall resulting from climate change may drive the parts of Amazon rainforest toward seasonal forests rather than savanna, argue researchers writing in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences

Amazon rainforest damage surges 67% in 2008

(12/20/2008)

The area of rainforest in the process of being deforested — razed but not yet cleared — surged in the Brazilian Amazon during 2008, according to new figures released by Brazil’s National Institute for Space Research (INPE). The announcement comes shortly after the Brazilian government reported a 4 percent increase in forest clearing for the year. Using an advanced satellite system that tracks changes in vegetation cover INPE found that 24,932 square kilometers of Amazon forest was damaged between August 2007 and July 2008, an increase of 10,017 square kilometers — 67 percent — over the prior year. The figure is in addition to the 11,968 square kilometers of forest that were completely cleared, indicating that at least 36,900 square kilometers of forest were damaged or destroyed during the year. The sum does not include areas that may have been selectively logged for commercial timber.

Future threats to the Amazon rainforest

(07/31/2008)

Between June 2000 and June 2008, more than 150,000 square kilometers of rainforest were cleared in the Brazilian Amazon. While deforestation rates have slowed since 2004, forest loss is expected to continue for the foreseeable future. This is a look at past, current and potential future drivers of deforestation in the Brazilian Amazon.

Biofuels, food demand may doom tropical forests

(07/14/2008)

Rising demand for fuel, food, and wood products will take a heavy toll on tropical forests, warns a new report released by the Rights and Resources Initiative (RRI).