Uncovering the mysteries of the imperiled giraffe, an interview with Julian Fennessy

|

|

Every school child knows the giraffe: with its record height, small horns, and tell-tale spots, it is hard to miss. Although well-known among school children and the public there has been a vacuum in giraffe research until recently.

Dr. Julian Fennessy probably knows the giraffe better than anyone. Trekking across savannah, forest, and the deserts of Africa, Fennessy is collecting genetic samples of distinct giraffe populations and overturning common wisdom regarding their taxonomies. It had long been accepted knowledge that the giraffe was made up of one species and several subspecies, however with Fennessy’s work it now appears that several of the subspecies may in fact be distinct species.

Julian Fennessy. |

Such discoveries could have large conservation impacts, since conservation funds and efforts are largely devoted to species. The giraffe has suffered significant declines in the past decade with the total population dropping some 30 percent across Africa.

“Sadly all the standard players are involved,” Fennessy told Monagabay.com. “A mix of habitat loss, habitat fragmentation, impacts of war and civil unrest, and poaching.”

When told that giraffes are threatened, Fennesy said, people are “surprised – often in complete shock, although on the other spectrum some quite vehemently deny such a statement! Giraffe are everywhere, that is what I keep hearing from those who safari across the continent, but sadly they are not in the large numbers we hoped.”

Founding member of both the Giraffe Conservation Foundation (GCF) and the International Giraffe Working Group (IGWG), Fennessy is working tirelessly to conserve giraffe species, subspecies, and distinct populations. As he puts it, “I wish I had more hours in the day…”

Fennessy discussed researching giraffes, unraveling their taxonomic mysteries, and building conservation efforts with Mongabay.com in March 2009.

Described as in ‘dire straits’ the West African giraffe in Niger numbers less than 1,000. Photo by: JP Suraud. |

SCIENTIST PROFILE

Mongabay: What is the focus of your research? What is your background?

Julian Fennessy: The focus of my personal research is broad, but really can be best summed up as trying to find out what the current status of giraffe populations and (sub)species are in the wild. On a finer scale, with many others, I am looking at individual populations more closely to help build up a greater profile of giraffe life history – something significantly lacking.

I have a Bachelors of Applied Science in Natural Resource Management and subsequently undertook many years of field work/research which allowed me to write up a PhD on the ecology of giraffe in Namibia’s northwest.

However, field work and an enthusiasm to increase the profile of giraffe and their long-term conservation and management, has been the driver to moving me forward.

Mongabay: What led you to focus on giraffes?

Julian Fennessy: Since my first trip to Africa when I was 16—as a Rotary Exchange Student—I decided life was not about spending time behind a desk and the 9-5 grind, but is was definitely not the giraffe that grabbed my attention. Rhinos were top on the list but after returning to Southern Africa (after my undergraduate degree) and subsequently working on a project researching elephants and giraffe in the north-western desert of Namibia (amongst other things), I decided there was too much politics and egos in elephants and amazingly stumbled across the paucity of knowledge about giraffe. So…giraffe it was; I found a niche and ran with it!

Mongabay: Do you have any advice for students hoping to become conservation scientists?

Julian Fennessy: Believe in yourself! If you really want to do something or be somewhere, you can. We live at a time of amazing opportunities, the world is so small and the desire to learn is as great as ever.

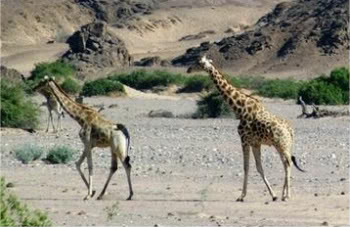

Tracking the Angolan giraffe in Namibia. Photo by: Julian Fennessy. |

I was not an ‘A’ grade student by any stretch of the imagination but realized that many people who have have PhDs and become ‘famous’ are not always what the television or books show. This may be outlandish but many of them struggle socially and their connection to how their research can truly apply to conservation and management on the ground, and in turn support community initiatives and social and economic awareness for those living with wildlife, is limited. Therefore, put everything in context, take all with a grain of salt and look at the bigger picture – but of course get the basics down pat and if lucky learn from a mentor or someone who wants to share experiences and listen to you. Oh…and enjoy!

Mongabay: What is your favorite place to work in Africa?

Julian Fennessy: That is a tough one – each place is magical and has its pros (and some cons). The rawness of Zambia, the beauty of the Reticulated giraffe roaming across northern Kenya, the deserts of Namibia and Niger, and of course, the ‘package’ that is the Okavango Delta in Botswana. So…in a nutshell, I do not have one special place but what makes somewhere special is the people you are with and the experiences you have.

Close-up of Angolan giraffes. Photo by: Julian Fennessy. |

GIRAFFFE: UNLOCKING NEW SPECIES

Mongabay: What is the role of the giraffe in their ecosystems?

Julian Fennessy:Giraffe are landscape changers, maybe not to the same degree as elephant and in some environments rhino, but they definitely open up areas and promote growth of new forage for them and other smaller browsers to make the most of.

Some interesting research in Kenya highlighted that when areas protected from herbivores, some Acacias declined and the knock on effect to other species e.g. ants, was considerable: http://news.mongabay.com/2008/0110-ants_trees.html

Such research is fascinating and highlights that we know very little about ecosystems, the species that have evolved in them, and the role they play – happy learning!

Mongabay: So far you have shown that six subspecies of giraffe may in fact be separate species. What is the process of moving an animal from subspecies status to species?

Julian Fennessy: Using genetic based research at least six potential species have been highlighted, however, a few more populations are still to be sampled – part of the ongoing work I am involved with. The process of moving an animal from subspecies status to species should be easier said than done (although timely and depends on who you know I am sure!) but the lack of primary data collection (scientists going to the field to collect samples from the ground and truth appropriately) is the fundamental flaw in this debate.

The Masai giraffe in Kenya. Photo by: Greg Edwards. |

Much of the debate around giraffe taxonomy is that ‘desktop’ science with limited knowledge of giraffe pelage (coat) patterns, historical and current range, ecological and geographic separation and now genetic variation, has resulted in a mess of taxonomy which has in all practicality gone beyond repair. We need to start again, we need to use the historic assumptions and classifications coupled with appropriate field data, research, and technology to build their status from the ground up. Whether it is one, two or more species, and in turn as many or more subspecies, it is important to the long-term conservation and protection of threatened populations.

Mongabay: What are the primary differences between species and subspecies?

Julian Fennessy: Traditionally, and in the most simplistic taxonomic terms, if two individuals could mate and produce viable and fertile offspring, then they were considered from the same species. However, if they were not fertile or could not reproduce, then they were assumed to be distinct species.

However, taxonomy is part science, part art, with more than 20 published species concepts to help define species level differentiation.

Julian Fennessy using a dart gun with a remote biopsy needle (drop darts) to take tissue/skin samples from the giraffe. “The dart hits the giraffe in the preferred spot around the rump and more than often drops off with a small piece of tissue for DNA analaysis – simple! Non-invasive! And if it does not drop off, the giraffe will swish its tail and knock it off to be collected,” Fennessy said. Photo by: Julie Larsen Maher. |

There is so much uncertainty in the current taxonomy of the giraffe that no one for sure can put their hand on their heart and say there is this many species or that many subspecies. Only time and dedicated data driven research will help us unravel this cryptic question – something the Giraffe Conservation Foundation , International Giraffe Working Group and Henry Doorly Omaha Zoo Centre for Conservation and Research are collaborating on.

Mongabay: How many giraffe species are recognized now? Which are the most endangered?

Julian Fennessy: Currently, and again this is based on the uncertainty in giraffe taxonomy, only one (1) species is recognized – Giraffa camelopardalis.

Within this species, nine (9) different subspecies are recognized:

- G.c. angolensis, Angolan or Smoky giraffe

- G.c. antiquorum, Kordofan giraffe

- G.c. camelopardalis, Nubian giraffe

- G.c. giraffa, South African giraffe

- G.c. peralta, Niger or West African giraffe

- G.c. reticulata, Reticulated or Somali giraffe

- G.c. rothschildi, Rothschild or Baringo giraffe

- G.c. thornicrofti, Thornicroft’s giraffe

- G.c. tippelskirchi, Masai giraffe

However, recent genetic research we have been involved with has highlighted that these (sub)species are distinct, species level separation (see: http://news.mongabay.com/2007/1220-giraffes.html). Based on this work and more we are undertaking, research indicates that the following, at least, are up for potential species status (note that all populations have yet to be sampled): West African, Reticulated, Rothschild, Masai, South African and Angolan giraffe.

Of all giraffe populations, it appears that some are in dire straits and others number less than 1,000. Specifically, the West African, Rothschild and Thornicroft’s giraffe have very low numbers, the latter has possibly always had a small population. However, little is known of the population numbers of Kordofan and Nubian giraffe as they inhabit areas of extreme civil unrest. Numbers of Reticulated giraffe are assumed to have plummeted over the last decade from nearly 30,000 to around 5,000 whilst encouragingly, numbers of giraffe in Southern African seem to be stable and/or increasing.

Mongabay: You are currently working to see if Thornicroft’s giraffe is a separate species as well. Any results you would like to share?

Stay tuned…the preliminary results are due out within the month and hopefully we can again highlight the important differences in this giraffe (sub)species to those across the continent which one would expect considering their geographic isolation, and of course pelage (coat) patterning.

Mongabay: How is discovering the actual taxonomic differences among giraffes important for conservation?

Julian Fennessy: This is not just a matter of keeping geneticists or taxonomists in business or the age old argument of ‘splitters’ vs. ‘clumpers’. For me it is simple – with better understanding of the taxonomic difference of giraffe populations, as well as a greater understanding of their current (and historical) population numbers and distribution, one can then build up a scenario of what is happening to them as distinct biological units which may or may not require targeted conservation and management – independent of whether the broader taxonomic question of species vs. (sub)species.

The fundamental questions we face regarding giraffe’s actual taxonomic differences are critical since protective legislation is generally afforded based on the term “species.”

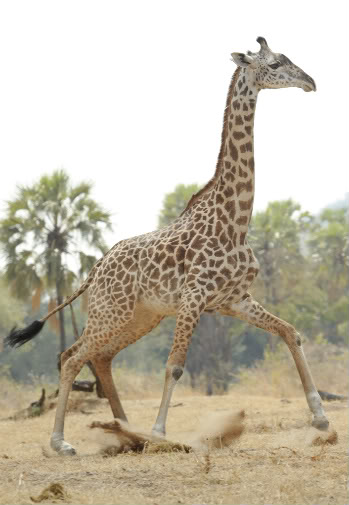

Thornicroft’s giraffe from Zambia’s South Luangwa Valley. Photo by: Julie Larsen Maher. |

THREATS TO GIRAFFES

Mongabay: Are people often surprised to hear that giraffes are endangered?

Julian Fennessy:Surprised – often in complete shock, although on the other spectrum some quite vehemently deny such a statement! Giraffe are everywhere, that is what I keep hearing from those who safari across the continent, but sadly they are not in the large numbers we hoped. Some populations and (sub)species are fairing better than others, which is the same for much wildlife across the world.

Mongabay: It is currently thought that giraffe populations have dropped 30 percent in a decade. What are the reasons for such a drastic decline?

Julian Fennessy: Sadly all the standard players are involved – a mix of habitat loss, habitat fragmentation, impacts of war and civil unrest, and poaching. Wildlife the world over is in decline with very few species on the rise. As giraffe require larger areas to survive than many other species, a loss in habitat quality and availability has been devastating, let alone an easy prey in areas of conflict.

Mongabay: You were very involved in having the West African giraffe listed as an endangered species by the IUCN in 2008, how difficult is such a process?

Julian Fennessy: Data, data, data – that is the key! The process can be as easy or difficult as the population allows. We have some good researchers and local NGOs in Niger collaborating with government and international partners who have monitored and censused the population for many years now. We have a good understanding of their numbers, distribution, and threats, as well as historical knowledge of where they once roamed and in what numbers.

Using the IUCN Red List Criteria, the process requires one to be methodical and apply as appropriate to the population/(sub)species – which in this case is one and the same.

Next on the list to assess is the Thornicroft’s giraffe based on the recent research we have been doing there and possibly followed by the Rothschild giraffe – I wish I had more hours in the day…

Mongabay: Any evidence of giraffes living in the Southern Sudan, which has only recently opened up to scientists again?

Julian Fennessy:Wildlife Conservation Society’s work in the past few years has re-highlighted the large numbers of antelope in particular that survived the devastating war in this region. Fortunately, other beasts like elephant and giraffe did better than buffalo and zebra. Chatting to the head of the country programme recently, giraffe are still surviving in a host of different areas and although maybe not in the thousands, the populations are apparently stable. Hopefully when things settle a little more and the road infrastructure/accessibility improves, I can get in their with a team to see what is happening with them and which (sub)species are surviving where!

Mongabay: You are a founding member of both the Giraffe Conservation Foundation (GCF) and the International Giraffe Working Group (IGWG), what can you tell us about these organizations?

Julian Fennessy:The Giraffe Conservation Foundation (GCF) is a new charity based in the UK which is endeavouring to support and profile giraffe conservation and management work across the African continent. As a new organization on the block, we are looking at supporting targeted projects in Kenya and Niger to start with, as well the continent-wide taxonomic research. But, there are so many projects and ideas which we could support – sadly just not the dollars. If anyone is keen to help out, feel free to drop me a line – happy to chat! Have a look online at the GCF website: http://www.giraffeconservation.org– coming to a webpage near you soon!

The International Giraffe Working Group (IGWG) sits under the banner of the IUCN Species Survival Commission, and in particular the Antelope Specialist Group. Established in 2003, the Group came together to look at ways of undertaking and providing support to giraffe conservation and research in both in-situ and ex-situ populations. We have been undertaking some collaborative research and conservation management support projects both in Africa and in the zoo world. As well, we produce a newsletter to try and bring the community together – this seems to be an effective tool which hopefully will grow as a resource (contact me for a copy or download online at: http://www.iucn.org )

Mongabay: What are your future plans?

Julian Fennessy: Personally, when I grow up…I would love to be a full-time giraffe ‘fundi’ (expert) with the capacity and support to look at what is happening to these critters across the continent and work with partners from all areas to increase our knowledge of giraffe and their profile, and subsequently improve their conservation and management. However, funding is and may always be limited so maintaining a strong foot in the giraffe world is important to me as an outlet – let alone a responsibility.

Related articles

Disappearance of elephants, giraffes causes ecological chain reaction

(01/10/2008)

The disappearance of elephants, giraffes and other grazing animals from the eastern African savanna could send ecological ripple effects all the way to the savanna’s ants and the acacia trees they inhabit, warns a new study published in the journal Science.

6 species of giraffe “discovered”

(12/21/2007)

Genetic analysis that the world’s tallest animal–the giraffe–may actually be several species, according to a study published in the open access journal BMC Biology. Existing taxonomy recognizes only one species of giraffe.

Photos of newborn baby giraffe at the Bronx Zoo

(05/21/2007)

A baby giraffe born October 30, 2006 at the Bronx Zoo in New York is doing well reports the Wildlife conservation Society (WCS). The youngster is the second offspring of Margaret Sukari, a 12-year old giraffe that lives on the African Plains’ Giraffe Lawn at the zoo.