Whether oil is succeeded by coal or renewables will have major impact on climate

The world must phase out emissions from coal by 2030 to avert dangerous climate change, said scientists speaking at the annual meeting of the American Geophysical Union in San Francisco.

Arguing that the planet will face environmental constraints well before fossil fuel resources are exhausted, scientists including Jim Hansen, Pushker Kharecha, and Ken Caldeira urged leaders to take bold action to leave coal in the ground and promote the development of low-carbon energy sources including wind, solar, and geothermal.

“Addressing the climate problem means addressing the coal problem,” said Caldeira, a researcher at the Carnegie Institution’s Department of Global Ecology at Stanford University. “Whether there’s a little more oil or a little less oil will change the details, but if we want to change the overall shape of the warming curve, it matters what we do with coal.”

“Oil and gas by themselves don’t have enough carbon to keep us in the dangerous zone for very long by themselves, but that’s assuming we do something about coal,” said Kharecha, a researcher at the NASA Goddard Institute for Space Studies (GISS) and Columbia University. “There are currently more than enough fossil fuels and coal to push us well past safe atmospheric CO2 levels.”

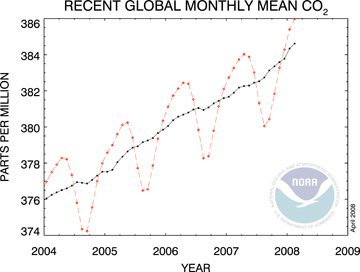

The 2007 rise in global carbon dioxide (CO2) concentrations is tied with 2005 as the third highest since atmospheric measurements began in 1958. The red line shows the trend together with seasonal variations. The black line indicates the trend that emerges when the seasonal cycle has been removed. (Credit: NOAA) |

Coal is the world’s most abundant of readily available fossil fuels, but emits 25 to 50 percent more carbon dioxide per energy unit than oil. As recoverable oil reserves dwindle, there will be increasing pressure to convert coal to liquid fuels as well as exploit unconventional fossil fuels like methane hydrates, tar sands, and oil shale. Developing these energy sources would carry even a higher cost to climate.

“We can replace oil with liquid fuels derived from coal,” Caldeira explained. “But these liquid fuels emit even more carbon dioxide than oil, so the end of oil can mean an increase in coal and even more carbon dioxide emissions to the atmosphere, and even more rapid onset of dangerous climate change.”

Modeling future climate change under different scenarios for energy use, Caldeira estimated that replacing oil with coal-to-liquids would lead to a 2°C (3.6°F) rise in temperatures by 2042 — three years earlier than a business-as-usual scenario with oil. Replacing coal with solar, wind, or nuclear would delay a 2°C (3.6°F) rise until 2056.

Jim Hansen, a prominent climate expert from NASA GISS and Columbia University, called for a carbon tax — rather than cap-and-trade — to encourage a shift away from carbon-intensive fuels. To minimize the economic impact and political cost of the scheme, he suggested returning the proceeds of the levy to taxpayers.

“A carbon tax will raise energy prices… but people will find ways to reduce carbon emissions… to come out ahead,” he said. “Product demand will spur economic activity and innovation.”

Hansen has set 350 parts-per-million (ppm) as the target for a safe level of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere. The current level is around 385 ppm and rising at a rate of more than 2 parts per million (ppm) year as a result of fossil fuel emissions, agriculture, and deforestation.