Independent of climate, forest cover in southern Amazon region may fall to 20% by 2016

Global warming aside, southern Amazon forest cover may fall to 20% by 2016

Rhett A. Butler, mongabay.com

September 3, 2008

|

|

Forest cover in the “Arc of Deforestation” of southern Amazonia will decline to around 20 percent 2016 due to continued logging and conversion of forests for cattle pasture and soy farms, report researchers writing in the journal Environmental Conservation. The results are independent of impacts resulting from climate change, which some researchers say could dry the Southern Amazon and turn it into a tinderbox.

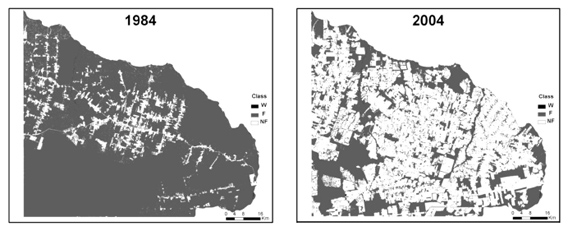

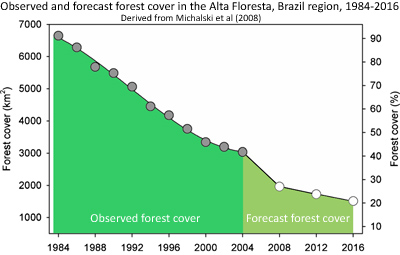

Analyzing high resolution satellite data from 1984 through 2004 for the Alta Floresta region in northern Mato Grosso, Fernanda Michalski, Carlos Peres and Iain Lake of the University of East Anglia found that forest cover declined from from 91.1 percent to 41.7 percent between 1984 and 2004. They note that while the deforestation rate has slowed to around 2 percent per year since peaking at more than 8 percent annually in late 1980s to mid-1990s, renewed expansion of road networks will enable loggers to increasingly exploit remaining forests, leading to degradation and likely eventual conversion for agricultural use. Overall Michalski and colleagues forecast that forest cover in Alta Floresta will fall to 21 percent by 2016, a decline of 77 percent since 1984.

A series of land-use maps representing the evolution of the landscape structure in the Alta Floresta region at four-year intervals throughout through study period. Land-cover classes are represented by water (W), forest (F) and non-forest (NF). Courtesy of Michalski et al (2008)

A series of land-use maps representing the evolution of the landscape structure in the Alta Floresta region at four-year intervals throughout through study period. Land-cover classes are represented by water (W), forest (F) and non-forest (NF). Courtesy of Michalski et al (2008)

The authors’ projections are based on a model that incorporates regional deforestation rates, changes in forest structure, and socioeconomic drivers of deforestation in the study area over the 20-year period. The results “indicate a critical threshold at 51% of forest cover in which landscape structure and connectivity changes abruptly.” Now that forest cover has dipped below this level the authors believe cover will trend downwards. To reserve course and maintain forest cover, Michalski and colleagues suggest that “environmental law enforcement, land-use planning and education programs” need to be effectively implemented.

“We suggest that the current proportion of forest cover should be maintained by ensuring the continuation of readily available data from satellite monitoring as well as in situ law enforcement of Brazilian forest legislation, especially during the dry season when most of the deforestation takes place,” they write.

Forest cover and predicted between 1984 and 2016 in the study area.

|

Failing to curtail deforestation in the region will have significant ecological impacts and may impair the Brazilian government’s plan to promote sustainable development, the authors warn.

“If observed deforestation probabilities remain unchanged, we predict that only 21% of the forest cover will remain in the study region by 2016, well below estimates of sustainable forest cover in the Amazon based on metrics of landscape structure, ecosystem services under future climate change scenarios, and current levels of bird and mammal species persistence,” Michalski and colleagues write. “If current rates of deforestation continue in this region, the region will reach a critical point where local extinctions of forest species will rapidly accelerate.”

“Aggressive colonization frontiers can rapidly reach critical landscape structure thresholds beyond which more benign land-use alternatives such as the creation of new protected areas are no longer available unless significant efforts in capital-intensive habitat restoration can be deployed,” the authors continue.

“A more cost-effective preventative approach should be followed based on greater enforcement to achieve wider compliance of private landholders with existing environmental laws. Additionally, the creation of protected areas in public land and environmental education of landowners in private areas can help maintain and conserve forests and biodiversity,” they conclude.

Citation:

Fernanda Michalski, Carlos Peres and Iain Lake (2008). Deforestation dynamics in a fragmented region of southern Amazonia: evaluation and future scenarios. Environmental Conservation 35 (2): 93-103 doi:10.1017/S0376892908004864

Related articles

|

Subtle threats could ruin the Amazon rainforest

(11/7/2007) While the mention of Amazon destruction usually conjures up images of vast stretches of felled and burned rainforest trees, cattle ranches, and vast soybean farms, some of the biggest threats to the Amazon rainforest are barely perceptible from above. Selective logging — which opens up the forest canopy and allows winds and sunlight to dry leaf litter on the forest floor — and 6-inch high “surface” fires are turning parts of the Amazon into a tinderbox, putting the world’s largest rainforest at risk of ever-more severe forest fires. At the same time, market-driven hunting is impoverishing some areas of seed dispersers and predators, making it more difficult for forests to recover. Climate change — an its forecast impacts on the Amazon basin — further looms large over the horizon.

Future threats to the Amazon rainforest

(7/31/2008) Between June 2000 and June 2008, more than 150,000 square kilometers of rainforest were cleared in the Brazilian Amazon. While deforestation rates have slowed since 2004, forest loss is expected to continue for the foreseeable future. This is a look at past, current and potential future drivers of deforestation in the Brazilian Amazon.

Industry-driven road-building to fuel Amazon deforestation

(3/12/2008) Unofficial road-building will be a major driver of deforestation and land-use change in the Amazon rainforest, according to an analysis published in Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B. Improved governance, as exemplified by the innovative MAP Initiative in the southwestern Amazon, could help reduce the future impact of roads, without diminishing economic prospects in the region.

Greenhouse gas emissions have already caused the Amazon to dry

(2/27/2008) Anthropogenic emissions of greenhouse gases have already caused the Amazon to dry, finds a new study published in Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B.

|

Half the Amazon rainforest will be lost within 20 years

(2/27/2008) More than half the Amazon rainforest will be damaged or destroyed within 20 years if deforestation, forest fires, and climate trends continue apace, warns a study published in Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B. Reviewing recent trends in economic, ecological and climatic processes in Amazonia, Daniel Nepstad and colleagues forecast that 55 percent of Amazon forests will be “cleared, logged, damaged by drought, or burned” in the next 20 years. The damage will release 15-26 billion tons of carbon into the atmosphere, adding to a feedback cycle that will worsen both warming and forest degradation in the region. While the projections are bleak, the authors are hopeful that emerging trends could reduce the likelihood of a near-term die-back. These include the growing concern in commodity markets on the environmental performance of ranchers and farmers; greater investment in fire control mechanisms among owners of fire-sensitive investments; emergence of a carbon market for forest-based offsets; and the establishment of protected areas in regions where development is fast-expanding.

Deforestation a greater threat to the Amazon than global warming

(2/25/2008) If past conditions are any indication of future conditions, the Amazon rainforest may survive considerable drying and warming caused by global warming, argue researchers in a paper published in Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B.

Fire policy is key to reducing the impact of drought on the Amazon

(2/19/2008) Gaining control over the setting of fires for land-clearing in the Amazon is key to reducing deforestation and the impact of severe drought on the region’s forests, write researchers in a paper published in Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B.

How much would it cost to end Amazon deforestation?

(1/27/2008) With Brazil last week announcing a significant jump in Amazon deforestation during the second half of 2007, the question emerges, how much would it cost to end the destruction of Earth’s largest rainforest?

55% of the Amazon may be lost by 2030

(1/23/2008) Cattle ranching, industrial soy farming, and logging are three of the leading drivers of deforestation in the Brazilian Amazon. As commodity prices continue to rise, driven by surging demand for biofuels and grain for meat production, the economic incentives for developing the Amazon increase. Already the largest exporter of beef and the second largest producer of soy – with the largest expanse of “undeveloped” but arable land of any country – Brazil is well on its way to rivaling the U.S. as the world’s agricultural superpower. The trend towards turning the Amazon into a giant breadbasket seems unstoppable. Nevertheless the decision at the U.N. climate talks in Bali to include “Reducing Emissions From Deforestation and Degradation” (REDD) in future climate treaty negotiations may preempt this fate, says Dr. Daniel Nepstad, a scientist at the Woods Hole Research Institute.

|

Globalization could save the Amazon rainforest

(6/3/2007) The Amazon basin is home to the world’s largest rainforest, an ecosystem that supports perhaps 30 percent of the world’s terrestrial species, stores vast amounts of carbon, and exerts considerable influence on global weather patterns and climate. Few would dispute that it is one of the planet’s most important landscapes. Despite its scale, the Amazon is also one of the fastest changing ecosystems, largely as a result of human activities, including deforestation, forest fires, and, increasingly, climate change. Few people understand these impacts better than Dr. Daniel Nepstad, one of the world’s foremost experts on the Amazon rainforest. Now head of the Woods Hole Research Center’s Amazon program in Belem, Brazil, Nepstad has spent more than 23 years in the Amazon, studying subjects ranging from forest fires and forest management policy to sustainable development. Nepstad says the Amazon is presently at a point unlike any he’s ever seen, one where there are unparalleled risks and opportunities. While he’s hopeful about some of the trends, he knows the Amazon faces difficult and immediate challenges.