Arctic sea ice falls to second lowest on record

Arctic sea ice falls to second lowest on record

mongabay.com

September 16, 2008

|

|

Arctic sea ice retreated to the second lowest level on record but remains about 9 percent above the low set last September, reports the NASA and the National Snow and Ice Data Center in Boulder, Colorado.

The ice covered 1.74 million square miles on Friday, the lowest extent this year and just shy of last year’s mark of 1.59 million square miles, the lowest since record-keeping began in 1979.

The Arctic is reaching the end of its melt season. Soon sea ice will begin to refreeze and expand.

Researchers say shifting currents and warmer waters are triggering ice melt, a process which builds on itself since sea ice helps reflect sunlight back into space, cooling the region. When sea ice melts, the dark areas of open water absorb the sun’s radiation, trigger a positive feedback loop that worsens melting. When there is less cloud cover, the effect is intensified.

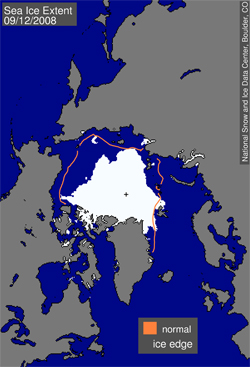

Arctic sea ice extent for September 12, 2008, was 4.52 million square kilometers (1.74 million square miles). The orange line shows the 1979 to 2000 average extent for that day. The black cross indicates the geographic North Pole. Sea Ice Index data. Credit: National Snow and Ice Data Center |

Last December scientists at the fall meeting of the American Geophysical Union in San Francisco warned that Arctic Ocean could be nearly ice-free at the end of summer by 2012, a dramatic forward revision of previous forecasts that the region would have ice-free summers around 2030.

“The Arctic is often cited as the canary in the coal mine for climate warming,” NASA climate scientist Jay Zwally told the Associated Press at the time. “Now as a sign of climate warming, the canary has died. It is time to start getting out of the coal mines.”

Environmentalists are concerned that the loss of summer sea ice could have dramatic implications for wildlife — like polar bear and walrus — that depend on pack ice for feeding. At the same time, some developers welcome declining ice cover in that it could make it easier to exploit the Arctic’s rich mineral, oil and gas deposits. Melting has already triggered a scramble between Canada, Russia, the U.S., Denmark, Sweden and Norway over rights to seabed resources.