The extinction of the baiji a ‘wake-up call’ to conserve vaquita and other cetaceans

An interview with Dr. Jay Barlow:

Extinction of the baiji a ‘wake-up call’ to conserve vaquita and other cetaceans

Jeremy Hance, mongabay.com

August 25, 2008

|

|

In December of 2006 an expedition spent six weeks surveying the Yangtze River in China for one of the world’s rarest cetaceans, the baiji. Also known as ‘The Goddess of the Yangtze’ the shy river-dolphin had roamed the river for millions of years locating fish with echolocation. The survey came back empty-handed without a spotting a single dolphin. Dr. Jay Barlow, a member of the surveying team, described his emotions on the expedition’s findings in an interview with Mongabay.com: “I was stunned. I knew the species was in trouble, but I did not think they were already gone. We really had not seen the extinction of a large mammal species in 50 years, so we grew complacent.”

The expedition sealed the baiji’s fate for most of the scientific community and the world. There has been no verified sighting of the baiji since the expedition. In August of 2007 a video purporting to be of the dolphin emerged, but there is debate as to whether it actually shows the animal. Barlow does not believe the baiji will stage a return. “I have no optimism left for this species,” he says. “It is gone. This is indeed a sad end for an entire arm of the evolutionary tree that has been around for 20 million years.”

Jay Barlow (on left) and Xiujiang Zhou (Institute of Hidrobiology, Wuhan) stand before a monument that marks the entrance to a baiji protected area on the Yangtze River. Now, no baiji are left to protect. |

Barlow describes the preventable extinction of the baiji as a “wake-up call” for conservation efforts. Currently, Barlow is working closely with scientists and Mexican officials to save another species from the baiji’s fate. The smallest cetacean in the world, the little-studied vaquita, is now the most endangered. Barlow believes there are positive developments in the vaquita’s conservation: “I see Mexico moving strongly, for the first time, to save the vaquita, a critically endangered porpoise in the Gulf of California. For the first time I am optimistic about its chance at survival.”

The reasons for the vaquita’s endangerment and the baiji’s extinction are, according to Barlow, the same: “poor, artisanal fishermen who were just trying to get by”. He goes on to say that the only way to save the vaquita is to “get all the entangling nets out of their habitat. Once populations get down to 150 individuals (the 2007 estimate for vaquita), you have no options left. You must eliminate human-caused mortality and let the species recover as fast as possible.”

Barlow has worked with more than just species on the brink. In mid-August it was announced by the IUCN that due to continuing population growth, the humpback whale would be reclassified from ‘vulnerable’ to ‘least concern’. Barlow, who has been one of a large number of scientists studying humpback populations, sees this as a rare sign of hope for the ocean’s inhabitants. He told Mongabay.com that “it shows the damage we cause is often reversible if we have the willpower to try.”

In the following August 2008 interview, Dr. Jay Barlow answers questions about the world’s most imperiled cetacean species and finds hope in one of its great success stories.

Mongabay: How did you become interested in marine biology?

Jay Barlow: I watched way too much Jacques Cousteau when I was a kid. Seriously. That got me interested in diving, which got me interested in marine biology, which got me to Scripps Institution of Oceanography. After that, it was just chance and circumstance that got me working on marine mammals. I thought I wanted to study lobsters.

Mongabay: What is you favorite place to do fieldwork?

Jay Barlow: My favorite place is the southern Gulf of California. The seas are typically calm, the landscape on shore is amazing and the oceans are brimming with life.

Mongabay: Do you have any advice for students hoping to become conservation scientists?

Jay Barlow: You have to realize that there are more qualified people than there are jobs. You should look into what specializations are in short supply and target your education so that you can fill that gap. Don’t expect the job to be fun. There is no more rewarding job, but like any job done well, it requires a lot of work and a lot of preparation, training, and education.

THE BAIJI

Mongabay: Having worked with some of the rarest-of-the-rare cetaceans, how do you keep optimistic about their fates?

The Baiji or Yangtze River Dolphin. Photo by Wang Ding and courtesy of the Institute of Hydrobiology, Chinese Academy of Sciences. |

Jay Barlow: I was involved in the survey for the baiji or Yangtze River dolphin in 2006. On that survey we failed to see a single one, and the IUCN Red List now classified the species “possibly extinct” and I have no optimism left for this species. It is gone. This is indeed a sad end for an entire arm of the evolutionary tree that has been around for 20 million years. However, in the wake of this disappointment, I see Mexico moving strongly, for the first time, to save the vaquita, a critically endangered porpoise in the Gulf of California. For the first time I am optimistic about its chance at survival. There will be failures, but we cannot give up.

Mongabay: As a Chief Scientist of the Scientific Committee for Baiji.org can you describe the work that you have done with the organization?

Jay Barlow: I was first consulted when the Yangtze River survey was being planned. I have previous experience surveying for Amazon river dolphins in Colombia and experience with marine mammal survey design in general. I participated in the pilot survey on the Yangtze in April 2006, and during that survey we designed the larger survey that was accomplished in November and December of that year. Since the survey was completed, I’ve helped coauthor three publications… one documenting the demise of the baiji, and two presenting the results of the visual and acoustic surveys for finless porpoises in the Yangtze.

Mongabay: What was your reaction to the news in December 2006 that the baiji was likely extinct?

The Baiji or Yangtze River Dolphin. Photo by Wang Ding and courtesy of the Institute of Hydrobiology, Chinese Academy of Sciences. |

Jay Barlow: Like all of those involved with the survey, I was stunned. I knew the species was in trouble, but I did not think they were already gone. We really had not seen the extinction of a large mammal species in 50 years, so we grew complacent. We have heard “wolf” cried too many times and do not recognize a real wolf when we see one. This has been a real wake-up call.

Mongabay: What are the reasons for the baiji’s demise? Are their lessons that can be learned from the baiji?

Jay Barlow: The reason they went so quickly was because of fishing. They were killed by gillnets, rolling hooks and dynamite fishing. You will hear people blame pollution and dams and river traffic, and maybe these would have eventually driven them to extinction, but really it was poor, artisanal fishermen who were just trying to get by. The main lesson, I think, is not to be lulled into complacency by the appearance of progress. China established reserves for the baiji, but these were just “paper reserves”. On our survey, we saw fishing vessels with illegal gear tied up next to enforcement vessels. Business was conducted as usual outside and inside the reserves. Fishing is still allowed within the oxbow lake that ostensibly has been set aside for finless porpoise. Someone should have been screaming “look … the emperor has no clothes”.

Mongabay: Do you think there’s still hope for the baiji? How many individuals would be needed to allow the animal a chance to comeback from extinction?

Jay Barlow: I have no optimism left for this species. If a dozen could be found, safely captured, and put into a world-class captive rearing facility, they might have chance. But we could not even find one.

VAQUITA

Mongabay: If the baiji is extinct, the vaquita has the dubious distinction of being the next most endangered cetacean. What must be done to save the vacuity from extinction?

Jay Barlow: The immediate threat to the vaquita is the same thing that did in the baiji. Small-scale artisanal fishing. What must be done, immediately, is to get all the entangling nets out of their habitat. Once populations get down to 150 individuals (the 2007 estimate for vaquita), you have no options left. You must eliminate human-caused mortality and let the species recover as fast as possible.

Mongabay: What are the threats to the vaquita?

Jay Barlow: Other than fishing nets, there are no proven threats. The upper Gulf of California remains a highly productive area. Vaquita there are fat and pregnancy rates are what we expect for the species. Pollution levels in their tissues are low. You may hear concerns about the lack of Colorado River flow into the northern Gulf, but productivity there is not driven by input of river nutrients. Although river diversions for agriculture are directly threatening other species, it is not an immediate threat for vaquita.

Mongabay: What is the nature of your work with Vaquita.org?

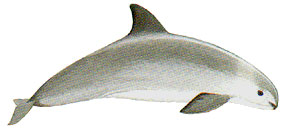

Courtesy of the Marine Mammal Commission The elusive vaquita, first described only in 1958, is found in the shallow (less than 50 m deep), near shore (within 40 km) waters of the northern Gulf of California, Mexico. |

Jay Barlow: I am a scientific adviser to that organization, but my most active role in vaquita conservation has been as a U.S. Government employee of NOAA. My job there has allowed me to work closely with Mexican colleagues to document the abundance and current status of the species. I conducted the first aerial survey for the species and published the first abundance estimates. This year our agency, the National Marine Fisheries Service will be conducting a major new research project in collaboration with Mexico’s National Institute of Ecology (lead by my wife, Barb Taylor). Together we hope to develop acoustic methods to more accurately monitor the status of the population. We need to be able to quickly determine whether conservation efforts are being effective at reversing population declines. We don’t have time to make mistakes. If efforts to save the species are inadequate, we need to know now.

Mongabay: Is enough work being done to save the vaquita in time? Is the newest resolution from the 2007 IWC conference sufficient?

Jay Barlow: Resolutions and “paper reserves” are never sufficient. Progress can only be measured in the number of fishing nets removed from there habitat. However, I see signs of progress. This year, the Government of Mexico plans to close all net fisheries in the vaquita’s most critical habitat. Monitoring and enforcement will be key to see if this is sufficient. Laws and regulations are often easy to pass but difficult to enforce.

Mongabay: How does one balance the economic needs of fishermen in the Baja region and conserving the vaquita?

Though protected, totoaba (above), as well as the small porpoise known as the vaquita (below), fall prey to fishing nets in the Gulf of California — just another factor stifling the recovery of both species. (Credit: Omar Vidal)

Jay Barlow: We should not expect the poor, artisanal fishermen to burden all the costs of saving a species. This is a species endemic to Mexico, so obviously its survival should be a point of pride for the people of Mexico. However, I would also like to see governments and non-governmental groups in the rest of the developed world (especially the US and Europe) step up with cash to help find an economic alternative for the displaced fishermen.

HUMPBACK WHALES

Mongabay: You have written about numerous cetaceans and marine mammals, are there particular species that you find most rewarding to work with?

Jay Barlow: I’m just finishing a 4-year project on estimating the population size of humpback whales in the North Pacific. We are finding that the population has increased 10-fold since then end of whaling (in 1966) and is now approaching 20,000. This project was especially rewarding because it involved the collaboration of over 400 individual researchers and because it shows that the damage we cause is often reversible if we have the willpower to try.

Mongabay: Can you describe the organization SPLASH for us?

Humpback whale in Alaska |

Jay Barlow: SPLASH is an informal consortium of humpback whale researchers throughout the North Pacific. It was founded by a steering committee of a dozen members who decided it would be a good idea to know how many humpback whales are found in their Ocean, how they moved, and whether they were healthy. Together we developed a research proposal, shopped it around for funding, and, when we secured the initial funding, started conducting research in winter of 2004. Most of the early funding came from the U.S. Government (NOAA’s Fisheries Service and Sanctuary Program). Later funding came from private sources, other countries, and the intergovernmental Commission for Environmental Cooperation. In the end, more than 400 researchers from 10 different countries participated in collecting data for SPLASH.

Mongabay: What have the studies of humpback whales uncovered regarding their population and behavior?

Humpback whale in Alaska |

Jay Barlow: SPLASH sampling just ended in 2006, but already the analyses have reveal much about the humpbacks in the North Pacific. We used photo-identification (pictures of their flukes) to estimate their abundance. The idea is, if you randomly photograph 4000 distinctive individuals at one time, then come back later and photograph 4000 more, some in your second sample will match those in the first. If 20% match, then you can figure that, in your first sample, you photographed 20% of the population, so the total population size must be 20,000. The actual statistics can be a bit more complicated than that, but that is the basic idea. Actually we obtained photographs from close to 8,000 individuals and estimated a population size of 20,000. This is great news for the whales and for conservation in general. Humpbacks have returned from near extinction to healthy numbers, all because we stopped whaling before it was too late. From all those photographs we also learned a tremendous amount about the migratory behavior of the whales.

Mongabay: What threats remain for humpbacks? Is climate change a threat to humpbacks and other cetaceans?

Jay Barlow: We are still concerned about humpback populations in the western Pacific where numbers are still less than 1,000. There, they could be threatened by a resumption of Japanese whaling. As a species, however, I no longer see any threats to their survival. Climate change will shake things up a bit, but humpback whales can feed on either fish or krill and have an enormous feeding range. Climate change is a bigger threat to ice-associated cetaceans, such as bowhead whales, belugas and narwhales. There habitat is likely to change much more dramatically than that of cold-temperate or sub-arctic species, like the humpback or blue whale.

Mongabay: You have done a lot of work with population modeling and abundance estimation, how can such approaches help save cetaceans and marine mammals?

Humpback whale in Alaska. Photos by Rhett A. Butler |

Jay Barlow: One thing I’ve found is that conservation efforts are slow to be implemented unless you have hard numbers. How large is the population? Is it increasing or decreasing? How many are being harmed by human activities. If you cannot answer those basic questions, it is hard to get legislation or regulations to limit any commercial activity. Although, in an ideal world, management of human activities would be precautionary in the face of uncertainty, in reality this doesn’t happen unless you have the numbers to quantify the risk.

Mongabay: What can people do to help save cetaceans and marine mammals?

Jay Barlow: At a grass-roots level, the most important thing you can do is to be aware of where your fish is coming from and how it was caught. Fishing is still the greatest threat to cetaceans worldwide, and fisheries kill hundreds of thousands of animals every year. The US has some of the most proactive measure to protect marine mammals, so it is good in general to buy US fisheries products. However, different methods of fish capture have different risks to marine mammal. A number of non-profit organizations have published guidelines for choosing “blue” fisheries products (which sounds tastier than “green fish”). Also, it is important to let your Congressional representatives know that a healthy ocean is important to you. It certainly is important to me.