Markets may save rainforests

An interview with Dr. Andrew Mitchell of the Global Canopy Program:

Markets could save rainforests

Rhett A. Butler, mongabay.com

August 18, 2008

|

|

Markets may soon value rainforests as living entities rather than for just the commodities produced when they are cut down, said a tropical forest researcher speaking in June at a conservation biology conference in the South American country of Suriname.

Andrew Mitchell, founder and director of the London-based Global Canopy Program (GCP), said he is encouraged by signs that investors are beginning to look at the value of services afforded by healthy forests.

Crisis of values

Speaking to an audience of more than 500 scientists at the annual meeting of the Association for Tropical Biology and Conservation, Mitchell said the world presently faces a crisis of values, which translates to threats to food security, energy security, and environmental security.

“These are combining to create a kind of a perfect storm that we have going on right now,” he said. “You see it in rising food prices, rising energy prices, and a great land grab to produce biofuels. The easiest way to grow these crops is to grab lands in the tropics… from rainforests.”

“Meanwhile the developing world sees climate change as a train crashing through their countries, but something that is not their fault,” Mitchell continued.

But hope is on the horizon.

Andrew Mitchell atop an observation tower just north of Manaus, Brazil |

Mitchell believes that valuing forests for the services they provide could play a critical role in addressing climate change, rural poverty, and the food crisis, as well as safeguarding biodiversity.

“Forests fall because they are worth more cut down than standing. This is a classic example of a market failure,” Mitchell told mongabay.com in an interview following his speech. “But ecosystem services could change that.”

According to Mitchell, the concept really gained momentum in 2005 after Michael Somare, the prime minister of Papua New Guinea, told developed countries at an international climate meeting that if they wanted tropical nations to stop cutting down their forests, they would have to pay them. Since then the idea has won wider support from interests ranging from environmentalists to business to politicians. Even some indigenous rights’ groups see the concept as offering potential to protect forests and improve rural livelihoods, provided it takes their historical land rights and access into consideration.

Four ways to reduce emissions from deforestation

Mitchell said the world is presently looking at four ways to deal with emissions from deforestation: First, plantation forestry, which has been slow to get approvals under the kyoto protocol’s cdm mechanism; second, redd or reducing emissions from deforestation and degradation, a proposed mechanism for compensating countries that reduce their deforestation rate; third conserved carbon stocks, which would pay countries for the carbon contained in their forests; and fourth, ecosystem services, a broader compensation scheme based on the value of the multitude of services provided by healthy forests. Of these, Mitchell has the most hope for payments for ecosystem services.

Mitchell said plantation forestry suffers from concerns over the use of alien species, lack of biodiversity, and whether local communities see benefits from industrial-scale plantations since up-front costs make it difficult for small projects to win approval.

Sir Michael Somare, Prime Minister of Papua New Guinea, hosts a meeting about the Forests Now Declaration in New York |

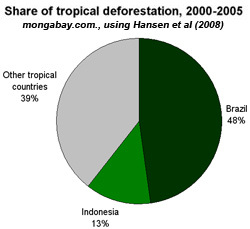

REDD, a concept which won tacit approval in last December’s climate talks in Bali and has been lauded by many for its capacity to reduce emissions and protect biodiversity, also has limitations in that the only countries that may qualify are those with high deforestation rates. Countries with low deforestation rates will see little funding under the proposed system since carbon credits are only issued for emissions reductions, not carbon stored.

A broader scheme, known as preventative or conserved carbon credits, is seen as a way to include countries that have effectively preserved their forests, but still faces some shortcomings. While the mechanism could incorporate other carbon-rich ecosystems, notably peatlands, U.N. negotiators were concerned that the sheer volume of carbon stored in global ecosystems could lead to an oversupply of credits, triggering a collapse in the price of carbon and therefore undermining the market and the incentive to reduce emissions. But Mitchell said that if the forest compensation system was expanded to include other ecosystem services, it may offer better incentives to conserve forests.

Mitchell compared forests to giant utilities that offer services on local, regional, and global scales. Locally forests offer watershed protection, stabilize soils, and buffer against flooding. At the regional and global levels, forests generate rainfall, moderate climate, and support biodiversity.

Andrew Mitchell addessing PNG delegation in Malaysia 2005 |

He cited the rainforest in the Brazilian Amazon as an example. The forest contains some 60-70 billion tons of carbon, discharges 55 percent of the world’s freshwater, and generates 20 billion tons of rain per day, supplying water to the $1 trillion agricultural industry in the La Plata river basin in Argentina.

Mitchell believes financial markets will eventually pay for this hugely valuable utility. He said emerging models — including FUNDECOR in Costa Rica and the Amazonas Initiative in Brazil — offer some clues on who will pay and at what price. In the end, Mitchell argued that future markets will be about more than just carbon and that payments for ecosystem services could drive billions of dollars per year to forest-owning nations.

“Philanthropy and taxes by governments aren’t going to be enough to fund forest conservation efforts on the kind of scale that’s going to be needed to have a real impact,” Mitchell told mongabay.com. “But for a market $10-15 billion is quite manageable. That’s about what we drink in wine and champagne every year in Britain. For a fraction of the percent of the three trillion dollar-a-year insurance business we could save forests.”

According to Mitchell the key to making ecosystem services markets a reality is political will to create a regulatory framework that can serve as a basis for investment. The idea is already gaining political momentum with the Forests Now Declaration in September 2007, the Lake Victoria Commonwealth Climate Change Action Plan in November 2007, the decision on REDD at the U.N. climate talks in Bali in December 2007, and a flurry of recent agreements signed between provincial and state governments in Brazil, Indonesia, and other countries. Mitchell noted that Prince Charles has become a high profile advocate for ecosystem services markets and that Bharrat Jagdeo, president of Guyana, has offered to turn over all his country’s forests for such a scheme.

The services and the buyers

With Suriname as the setting — the nation with the highest percentage of tropical forest cover of any country in the world — Mitchell talked extensively about the ecosystem services provided by the Amazon.

Mitchell stated that Brazilian researchers lead the world in understanding the full extent of biospehere-atmosphere interactions of tropical forests. Dr Antonio Nobre of INPA has revealed that the Amazon accounts for 16 percent global freshwater supplies and generates 20 billion tons of rainfall per day. He said that while scientists don’t yet know what would happen to rainfall if the Amazon is razed, replacing Brazil’s hydro capacity — which accounts for 70-80 percent of its electricity — would cost $100 billion. This figure implies a value of $260 per ha for water alone for Brazil’s remaining forests. Mitchell added that Brazil’s agribusiness — soya, beef and sugarcane — all depend on rain and that 40 percent of Brazil’s cars can run on ethanol. In other words, any decline in rainfall would have a tremendous impact on the Brazilian economy.

Peruvian rainforest canopy. Photo by Rhett A. Butler |

On a broader scale, Mitchell said that the Amazon appears to have a role in weather moderation as well, comparing it to a regional air-conditioning unit. The Amazon drought in 2005 coincided with record Caribbean hurricanes which caused more than $80 billion in insurance losses in the United States alone. The Amazon also helps stabilize climate by sequestering billions of tons of carbon in its vegetation and soils — this service would also add value. He speculated that the market may eventually distinguish between “dead carbon” — mainly emissions from energy that can be captured and stored (CCS) at a cost of $40 per ton of CO2 — and “living carbon” which is stored in forests and ecosystems at a fraction of the cost of CCS and can provide a sustainable livelihood for 1.4 billion people worldwide.

“The central issue in this whole debate is how we put a true value on standing rainforest to the world community,” he said.

Mitchell said that once a market is established, buyers could include utilities, agribusiness, hedge funds, banks, and even governments.

Amazonas and Iwokrama

Mitchell cited two examples of projects to show how ecosystem services payments are working today.

The Amazonas Initiative launched by the Brazilian state of Amazonas last year includes provisions to protect large tracts of forest while simultaneously improving the standard of living in remote rural areas. The initiative includes the Bolsa Floresta program which pays forest families living near Uatuma Reserve about $25 per month to not clear primary forest lands in return for making ‘no smoke’. Residents are also provided with health care, clean water, and greater access to education.

Mitchell also highlighted the recent agreement signed between the government of Guyana, and Canopy Capital, a private equity firm advised and set up by the Global Canopy Program. The deal, signed in March, secures the rights for Canopy Captal to measure and acquire a value for the ecosystem services of a million-acre (371,000 hectare) reserve of forest in Guyana. This, the first deal of its kind to be signed, has attracted investor interest from all around the world. Although deforestation rates in Guyana are presently low, the deal seeks to capitalize on the role that Guiana shield forests play in maintaining rainfall in South America. Canopy Capital plans to develop investment instruments like ecosystem services bonds that will be sold in financial markets. The proceeds will be split with 80 percent going to reserve and the communities of Iwokrama. Mitchell believes that because these services presently have no value in the markets, the price can only appreciate.

Kaieteur Falls outside Iwokrama Reserve, Guyana |

Mitchell noted that involvement of local people is key to the project’s success. He explained that scientists and development experts will work with local peoples to design sustainable businesses as well as forest monitoring programs. A similar project is being tested in the African country of Cameroon. Villagers are trained how to map field data with GPS units. All data is logged and put into a database that can be displayed on Google Earth. Communities swap information and can see things like when illegal loggers or miners are encroaching into their forest.

“The indigenous communities probably have the best track record of any group in looking after their forests and preventing deforestation,” he told mongabay.com. “The problem that we face is that under the REDD mechanism being developed by the UN, there is a danger that these groups won’t see compensation because they have a low deforestation baseline and are therefore not emitting. ”

“We need to think about how these communities who have succeeded in protecting their forests should get paid. As I see it, a method for this is the ecosystem services they are providing the world.”

Mitchell concluded by noting that carbon emissions will continue to have increasing financial, environmental and societal costs, making conservation actions increasingly valuable.

“It’s time to stop talking and start acting,” he said. “The world is waking up to this and will drive capital to the canopy.”

Mongabay: What do we need to get ecosystem services payments off the ground on a global scale?

Andrew Mitchell: In order to create these kinds of new markets there are basically four things you have to do. It begins with science. Scientists have to tell us what the services are and what tropical forests do for us. Scientists view them as a giant global system that can be broken into four major utilities: the Amazon, the Guyana shield, the Congo basin, and the Southeast Asian forest (primarily between Borneo and New Guinea). These utilities operate on both local and global scales in terms of the ecosystem services.

The next step is bringing in the environmental economists to work with the scientists to put a value on those services. The Amazon is producing 20 billion tons of moisture a day. What’s that worth? How do you price that?

Next you have to take that information into the policy arena and create an enabling framework to encourage payment for ecosystem services.

And the fourth thing that you need to do is go to the market and persuade people to pay for those services.

All of those four stages are what we are trying to influence at the present time.

Mongabay: How are you going to get people to pay for services which, to them, have no value because they are currently free?

Andrew Mitchell: I have no idea. My hunch would be that they would not wish to pay because they are getting it for free. And therefore there are two things that you can do to encourage their willingness to pay. In effect it is the carrot and the stick.

Andrew Mitchell beneath the scientific observation tower run by the Large-Scale Biosphere-Atmosphere Experiment in Amazonia (LBA). |

The carrot is that in the end it’s in their own interest to keep the rain coming, but they don’t recognize it at this time. But if you told a farmer in Mato Grosso that over the next 50 years or so the rain that is falling on his land is going to decline and he is not going to be productive and then asked him if he’d be willing to pay to prevent this, I think you would have a pretty compelling argument. You have to quantify. If you reduce the rainfall by 10% a decade, that will have a measurable effect on the productivity of their land. That needs to be demonstrated. Eventually he will say, “I need to keep land productive.” Either he is going to irrigate — which has a cost — or he might say “I’ll start paying for rain.” But that’s a stretch for most people. Being a common good, the problem is that if farmer A says, “I’ll pay” and farmer B says, “I won’t” then farmer B is getting a free ride. The ideal is to develop markets for this but the stick is taxation. In the future governments may choose to implement a tax to help protect the Amazon which is in the common interest. Producers of commodities which extract land from the Amazon may have to pay a rain-tax to protect the rest, even future certification schemes from overseas buyers might require it. With 9 billion to feed in the future we have to think differently.

Mongabay: You mentioned that in a meeting with Blairo Maggi, the largest soy producer in the Amazon and governor of Mato Grosso, he laughed when you mentioned paying for rain. How do you respond to these kinds of reactions?

Andrew Mitchell: I just happened to be in a meeting where Blairo Maggi was and I asked him a question in open forum, “How much money would you be prepared to pay Governor Braga of Amazonas to keep the rain coming?” and it made him laugh. But he didn’t laugh when he heard about the scientific paper by Yadvinder Mahli of Oxford University which demonstrated that his state was the one most at risk from rainfall reduction caused by predicted long-term climate change. That made him think again and he said, “Well, give me the paper.” It makes people realize that the probability of getting that kind of system to work is unlikely without regulations. So the stick part is regulations.

Now how would you apply a regulatory framework to protect the Amazon on the basis of its rainfall production? A scenario could be that governments would say, “A primary driver of deforestation is agribusiness in the Amazon.” Then a tax could be levied on agribusiness which is then used to protect the Amazon. If you want to cut it down to grow crops, then you have to pay to maintain the rest. There is a cost-benefit to that.

Mongabay: Could you mandate something like every agribusiness has to carry insurance that would then be used to fund forest protection?

Andrew Mitchell: Well that is a market mechanism. A regulatory mechanism is a government imposed tax. There is a precedent for that in Brazil because the communications industry has a tax levied on it to pay for putting in communication in the Amazon. The principal is that whilst we all enjoy good communication in the southeast of Brazil, the Amazon is very dispersed and needs good communication, so they levied a tax and in so doing, created a fund which is going to be used to improve the Internet for instance, throughout the Amazon.

Amazonas Secretary of State for Environment and Sustainable Development Virgilio Viana signs the Forests Now Declaration, while GCP Director Andrew Mitchell looks on |

Now these are principals that the government can do, why not do the same for agriculture? It is clearly in the interest of Brazil nationally to maintain its huge production capacity. Brazil has a tremendous opportunity to feed the world. The challenge is how to do that without cutting down the rainforest. And Brazil can do it. There is plenty of free land, probably 40 million hectares available of idle land which has been deforested and is not being used. The problem is it’s cheaper to cut down more forest to get more land than to restore those lands — that is something that needs to change. You need to create positive incentives for land restoration by reducing taxes, creating positive incentives for restoring the waterways, improving the land and so on. And you need to create penalties for cutting down the forest. At the moment it is simple: it is just cheaper to cut the trees and sell the timber to make more land to grow crops.

Let me touch base on the market-based mechanism. In a market-based mechanism you might create an insurance product for farmers to insure themselves against the loss of agricultural productivity. This could possibly also be applied on a much wider — regional or international — scale because the services of forests like the Amazon or the Congo Basin stretch over huge areas and therefore affect great numbers of people. For instance look at the La Plata Basin in Argentina. 70 percent of GDP, or one-trillion dollars, is based on agribusiness. This depends on rain driven by that low-level jet stream from the Amazon down to Argentina.

So this raises other questions. Is Argentina going to blame Brazil for turning off its rain tap? Does Brazil blame the United States for causing climate change and drying the Amazon? These are fascinating legal questions for the future but we have to act now. And there may be insurance for us based on the idea that protecting the Amazon is a good insurance policy against extreme weather events and other costs that we will suffer if the forest is destroyed.

Mongabay: What about strategies to value forests as living entities via an ecosystem services market?

Andrew Mitchell: Yes, another approach is to increase the value of the rainforest and ecosystem services could do that. At GCP, in collaboration with our colleagues in Asia and Brazil, we are putting forward the idea that large areas of tropical forest should be seen as a public ‘utility’, providing services we all use but do not yet pay for. We all understand that if you do not pay your electricity bill, you get cut off. It will be the same with these forests. From an investment point of view, if you show that this is a utility which today has a value of zero in markets, but in the future might have a higher value for two reasons: (1) the asset is declining, there is becoming less and less of it, like a good vintage of wine — the more you drink the higher value the remaining wine becomes; and (2) the ecosystem services rainforests produce are increasingly being recognized. If you go to the UN, to the CBD, the UNFCCC, in the corridors there is a lot of talk about the ecosystem services that forests provide. Three years ago nobody was talking like that, but now there is talk of implementing a regulatory mechanism which might help put a value on the ecosystem services.

|

Investing to save rainforests: An interview with Hylton Murray-Philipson of Canopy Capital

Last week London-based Canopy Capital, a private equity firm, announced a historic deal to preserve the rainforest of Iwokrama, a 371,000-hectare reserve in the South American country of Guyana. In exchange for funding a “significant” part of Iwokrama’s $1.2 million research and conservation program on an ongoing basis, Canopy Capital secured the right to develop value for environmental services provided by the reserve. Hylton Murray-Philipson, director of Canopy Capital, says the agreement — which returns 80 percent of the proceeds to the people of Guyana — could set the stage for an era where forest conservation is driven by the pursuit of profit rather than overt altruistic concerns. |

Separately from that, the private sector is beginning to act now because they sense there may be an opportunity where you can buy something cheap today which might have a higher value tomorrow. An example of that is Canopy Capital deal in Iwokrama, Guyana. They have bought the rights to the ecosystem services of 371,000 hectares. Those services have a value today of zero. Actually no. They now have a value because we have put a price on them. Canopy Capital has paid money for those services.

The investors have come into Canopy Capital because they want to help change the way we value the environment. I and Hylton Murray Philipson, an environmental corporate finance specialist whom I have had the pleasure of working with for a number of years, and the investors who joined us to make the Canopy Capital deal happen at Iwokrama, all also believe that the long term solution here lies not with philanthropy but with investment. So it’s creating a stream which will make money, not just a donation. The reason for that is there are not enough donors around to fix this problem. The idea is if you can create forest bonds or ecosystem service trading certificates, these kinds of things will acquire value over time. But it might be over decades. This is about patient capital. And the most important thing of all of this is that the end game is to improve the lives of the communities who depend on these forests. In the Canopy Capital deal, the way it is structured is that once the initial investments have been recovered, 80% of profits will go to Iwokrama and be dispersed amongst the community. Iwokrama already has an excellent system for doing that.

There are people saying, “Why did this investment happen, the very first in the world, in Iwokrama?” The answer is it is like a AAA-rated forest. The government is transparent. They have excellent community relations. The land title is known and so far not in great dispute. There is strong political leadership from the president of the country. These are the criteria which will bring capital to the canopy. And that investment will be disbursed amongst the communities and keep Iwokrama going.

|

The deal is also unique in that it is a model for the whole commonwealth. In other words, what goes on in Iwokrama will be seen by many other countries, which is why we hope it will be a success. And crucially it is a stepping stone to creating an integrated model to the whole of Guyana. So often what you need is a national scale approach to prevent leakage — if you stop deforestation in one place you don’t want it popping up somewhere else. We are hoping to work, and are working, closely with the government of Guyana to help create a national solution — a new development model — to meet the needs of the people and protect all the forests.

It’s really important to understand the community side of this. Some people say, “Okay, so you are going to pay people for ecosystem services now. That is just paying people to do nothing. So you’re going to pay them not to cut down their trees. What are they going to do? Sleep in hammocks and drink beer?” The answer is no because the communities know how to look after these forests. The indigenous communities probably have the best track record of any group in looking after their forests and preventing deforestation.

The problem that we face is that under the REDD mechanism being developed by the UN, there is a danger that these groups won’t see compensation because they have a low deforestation baseline and are therefore not emitting. REDD is about reducing emissions. If you’re not producing any emissions you don’t get paid. We need to think about how these communities who have succeeded in protecting their forests should get paid. As I see it, a method for this is the ecosystem services they are providing the world. These include the storage of carbon and the production of rainfall and moisture, the protection of biodiversity, the moderation of weather. All these sorts of things are extraordinarily valuable services that we just don’t recognize or pay for. But these give us a basis for the payment.

And in return for the payment two things can happen. The first is that because communities are stakeholders in what is effectively a business, they should benefit as the business grows. The second is that the system should offer employment to the communities to be the monitors of the forest.

2004 Nobel Peace Prize winner Professor Wangari Maathai and Goodwill Ambassador for the Congo Basin Forests, and Minister of Environment, Conservation of Nature, Water and Forests for the Democratic Republic of Congo, Pembe Didace Bokiaga, join Andrew Mitchell to sign the Declaration. |

One thing we are planning in Iwokrama and other areas is working with the community and discussing with them how we can set up a community-based Social and Ecosystem Service Monitoring program. This would be based on using hand-held computers where they could collect data on the forest. Not only of the mapping exercise which helps them know exactly where their land is and helps improve their land title. But also to know when illegal loggers or miners are coming in, or if fires are occurring. This information can be uploaded into a Google database which all communities can see. If there is a problem, we will be able to call in the StarVision satellite monitoring and look at the situation right down to one meter. So if there is a gold mine going on down there, we know. You can look at it next day by satellite. And if there is a real problem, then you can call up the authorities and deal with that. The communities are going to play a crucial role in that process and will benefit.

Mongabay: In the Iwokrama example, 80% is going to the communities, 4-6% is going to canopy research, and then the remainder goes going to the investors. Is that enough return for investors to satisfy their desire to return?

Andrew Mitchell: The answer is that I don’t know yet. It’s not quite structured like that. Basically, stage one is effectively to secure the assets and to have an arrangement with Iwokrama which allows us to construct the longer-term investment vehicle. But a kind of investment vehicle would be a long-term forest bond which would attract money from banks, insurance companies and other business, and high net worth individuals. This patient capital would be employed and invested in the market. The interest it would create would then be used to benefit the Iwokrama system and the community. Some of that interest may be returned to the investors. It depends how much of that they want. If they are patient investors they will say, “We don’t need too much. We are happy for our capital to be employed and will take a small return.” Then the balance for that interest will go to supporting the activities which maintain the ecosystem services in Iwokrama. We are looking into a microfinance unit as well that might help stimulate more biodiversity-based industries and businesses which the communities are already starting with very small amounts of money. It might be fish farming, butterfly farming, bird-watching ecotourism, or other kinds of things they want to do using their traditional practices. Small amounts of money could make a huge difference and some of those businesses may grow. All of that is a considerable part of the bond.

Mongabay: So Iwokrama is kind of a special case. What are some of the challenges to extend this model else where? I am thinking of land title.

Eminent primatologist and UN Messenger of Peace Dr. Jane Goodall signs the Declaration at the Clinton Global Initiative meeting in New York |

Andrew Mitchell: Let me say that at the moment I feel very optimistic because we have a fantastic opportunity over the next two to four years to create a global deal for forests. And we’ve never had such an opportunity in the past except perhaps when the Kyoto Protocol was originally put together. That opportunity was squandered and for a variety of reasons old growth forests were kept out of the Kyoto Protocol. Part of the reason for that was that people didn’t want industrialized nations to get off the hook by off-setting via forests. We wanted maximum attention on reducing industrial emissions. Quite right because the rich countries caused climate change, the poor ones didn’t. But as a result of this decision, there were no incentives to maintain forest through a market mechanism and the result has been rampant deforestation. The reason why forests fall is fairly simple; they have no value in global markets. Conservationists created a paper wall around these parks that collapses inwards when faced with the beef, soy, and palm oil. The opportunity costs of avoiding deforestation are massive, ranging from as little as one or two dollars in a poor country like Sri Lanka where there aren’t too many alternatives to as much as $3,000 for palm oil in Asia. Those prices are increasing today as demand for food rises and biofuels put extra demand on top of that. The REDD mechanism provides a significant opportunity for countries which are deforesting to reduce their emission rates.

REDD stands for reducing emissions from deforestation and degradation. It is not E for ecosystems, it is E for emissions. So REDD is not primarily designed to save ecosystems, it is designed to cut emissions. That means that the countries with low deforestation rates are not the primary target, because they are not emitting. And this is creating a division in the negotiations which has to be dealt with. The challenge is that we only have three major meetings left in the UN process to agree on the mechanisms for REDD. That will have to be done by December of 2009 in Copenhagen.

Now I feel cautiously optimistic because there is so much pressure now on forests and it is up to all the NGO community and scientific community to stand up and be counted and to put pressure on the delegates to come up with a solution. The great danger is when the best gets in the way of the good. Everybody desires something which is technically so perfect but it becomes financially unworkable because the transaction costs are so high.

That is what happened with the CDM mechanism and plantations. The idea was that you plant new trees to take carbon out of the atmosphere and it would be approved under the CDM mechanism. Well, guess how many have been approved: one. How many have been approved under energy: over 900. How do you explain it? The standard for forests is more complicated and higher.

This is creating a bad incentive for poor countries because they are losing out. So it was agreed at the U.N. talks in Bali, that countries with high deforestation rates should get into the market.

Andrew Mitchell in the canopy in Malaysia 2005 |

I think ecosystem services can offer countries with low deforestation rates a real opportunity to get paid for looking after their standing forests. I think the REDD mechanism will result in, initially, a credit mechanism for reducing deforestation emissions. So Brazil and Indonesia, and countries like that, which have high rates and reduce them and it becomes measurable. And yes, the methodology is daunting. I don’t want to go into all the details on the methodology. But we must not lose sight of the woods for the trees on the methodology issue and completely screw up the direction of travel. That is the best getting in the way of the good again. Honestly, we have to get a deal for forests which reduces their emissions but at the same time we need a deal for the standing forests; countries with high forest cover and low deforestation rates. Countries like Guyana, Suriname; countries like Gabon and even the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) have a pretty low deforestation rate at the moment. They are not going to get much money out of REDD unless it accommodates these standing forest countries. So one tactic is you get standing forests included under REDD as well as emissions. Then again there’s China and India who have cut down their forests and planted lots more. And they say they want those forests included as well. So you’ve got three classes of forests being discussed under the REDD mechanism at the moment which was originally designed to deal with emissions: forests that are emitting; standing forests that are not but are storing lots of carbon; and new forests, that sequester carbon. But the mandate of the UNFCCC convention — is that to reduce emissions. I don’t know how that is all going to work out.

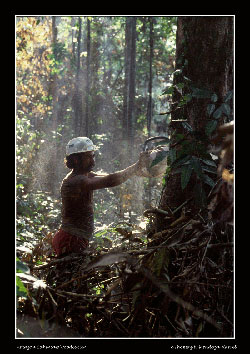

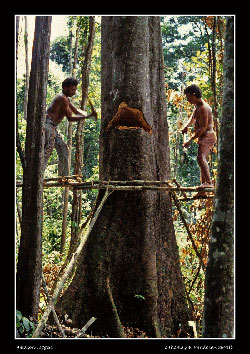

Rainforest destruction becomes industry-driven, concentrated geographically. |

So we are preparing for two tracks. The first is to include emissions and possibly standing forests under the REDD mechanism. If that doesn’t work, then what we need is a separate and parallel way of paying for these standing forests and I think ecosystem services is it. Ten years from now there may be a completely separate regulatory mechanism for that. And you know what? It might not be based on carbon, because there is much more to forests than carbon. It’s about living carbon. The UNFCC deals in dead carbon. What comes out of the back of your car or your factory is dead carbon. Carbon capture projects which are designed to take CO2 out of the atmosphere from a big power plant, liquefy it, and store it underground at forty dollars a ton. That is dead carbon; it doesn’t give you any co-benefits. You store a ton of carbon in the rainforest and you get massive co-benefits and you help alleviate poverty amongst the poor. The market may differentiate between living carbon and dead carbon in the future. But I think it could also become a market for ecosystem services because the standing forests provide so much for the world. So in the future I can see markets developing in that area and that is what we are trying to jump start with the Canopy Capital deal in Iwokrama.

Mongabay: How will this work in places where conditions aren’t as ideal as in Iwokrama, say Cameroon or Indonesia. Are you looking at a “forest index” as a solution?

Andrew Mitchell: Well, what are the conditions which will drive capital to the canopy for standing forests? Markets basically move on fear and greed. The fear factor is rising. By doing nothing, my costs may rise. I might get more hurricanes hitting Florida if I don’t try to fix this problem. That is a major incentive for the insurance industry to take account of environmental change. This is the fear motivation. As for greed, maybe I’m going to make a buck if I invest in these things. These two things are rising. You need regulatory mechanisms to drive the money. REDD is an example of that. We one day may have a regulatory mechanism for ecosystem services that would drive capital. GCP will be releasing a paper on this shortly entitled ‘Think PINC’, which stands for Proactively Investing in Natural Capital, to catalyze some thinking on this

Charlotte Streck of Climate Focus – convenor of the 2 day International REDD Roundtable in Brussels – and Jeff Horowitz of Avoided Deforestation Partners join GCP Director Andrew Mitchell to sign the Forests Now Declaration. |

Another major barrier that needs to be overcome is: “Who owns the assets? Who owns the forests?” Right now a majority of forests are publicly owned by government. Whilst that may be challenged by communities, this is the current situation. So governments that have good governance will attract business but the land rights issue is a big problem and something that really needs to be dealt with. It is in the communities own interest to do that. There needs to be some mechanism of figuring out who owns what, because most of this is not written down. So therefore community mapping programs and things like that are a good way to do it. The concept of shared ownership is another way to get them to pool together in this process. The community can share in a business that grows and there is equitable benefits sharing.

Another thing is that fund managers need to know where to put their money and at GCP we are looking at creating a forest index as a way to address this need. This forest index would work a bit like the FTSE4Good, which we have in London, which is a way for managers to look at businesses that are doing the right thing rather than the wrong thing. What we’re after is similar to ethical investment criteria applied to forests.

We would go about it in two ways. One would be to look at the countries — they range from AAA to sub-prime. That index would have a series of criteria. For a AAA rating, the country might have good governance, clear land title, and low deforestation. The ones that have poor governance, social conflict, and are difficult places to do business will fall down into the sub-prime category. Now people will say, “Well, that means all the money will go to AAA.” Well actually that isn’t how the market works because AAA is going to be expensive where as sub-prime is going to be cheap. A lot of the money will go to the cheap end of the market and help those countries too. It may be more risky but they can move up the index as things improve. What it will do is indicate to governments what they need to do to attract investments. This is how the market-based mechanism can work. The market has much, much more money than government. People say, “The market is not perfect. There is going to be good guys and bad guys.” Well, government systems aren’t much better either. None of this is perfect. The difference is the market can move quickly and it can bring large amounts of money to the system. But it needs to work under control to squeeze out the bad guys and encourage the good guys.

Deforestation is increasingly driven by industry rather than subsistence activities. Photos by Thomaz W. Mendoza-Harrell |

For example, Nick Stern has suggested that we need somewhere between ten and fifteen billion a year to cut deforestation by half. Those figures have been challenged and improved but let’s just take that as a number. There is not enough philanthropy around to come up with that sort of figure except perhaps in the big sovereign wealth funds from the Middle East, China and other areas. And maybe we could tap that. But for a market, that’s about what we drink in wine and champagne every year in Britain. It’s not so big. For a fraction of the percent of the three trillion dollar-a-year insurance business we could save forests. A fraction of a percent. And it might be one of the best insurance policies we could provide, but you’ve got to convince the insurance companies to do it. So for markets, this is doable. We just have to create the right framework and put the tools in place that markets can recognize.

The other thing we have to do is deal with the drivers of deforestation. That is another really important thing to do because it doesn’t matter how much you make these standing forest valuable if the families who are living there are going be paid five dollars to cut down a tree — unless you can pay them six, they are going to go on cutting. It’s a rational use of the environment for them. Of course, a lot of this value is not just economic; there are cultural, spiritual, and social values for forests. But that is a reality of the economic world. To outbid the drivers of deforestation would be very difficult and I think REDD is designed to work at the front line where it’s going to be most expensive and it is going to need most regulation. I think REDD is hopefully going to achieve that.

But away from the front lines, there are these giant areas of forest which need support as well. And possibly for something like $10-20 dollars a hectare, you can probably protect those forests. You can add up what that number is, and for the Guyana Shield it is around about 2.5 billion a year to protect those standing forests of the Guyana, Suriname, and French Guiana. It is a small price to pay for what you are getting and the market can provide it.

REDD isn’t necessarily going to deal with the drivers of deforestation because what drives deforestation is consumer demand, and to some extent poverty and the need for energy. What is driving deforestation today has changed. It has become industrialized. Massive business demands. We, the rich countries, are eating the forests because we demand palm oil, beef, soy, and timber. That is what is causing the forests to fall. So to deal with those drivers you need to, again, use the carrot and stick method. And we need to clean up the supply chain with certification mechanisms.

For example, there is nothing wrong with oil palm. It is in fact a miracle plant — a small family can grow a few palm oil trees and make money every year and it has taken Malaysia out of poverty, but at a huge cost. It’s not wrong to grow palm oil, just don’t grow it in the rainforest. There is often plenty of other land to grow this stuff on, but it is still cheaper to cut down the rainforests. That is what has to change. We have to create incentives for degraded lands and move the production of food onto those lands and utilize the investment. We must stop the production of these food crops and biofuels in rainforests. Now at the moment biofuels are not generally grown in rainforests and palm oil is not used as a biofuel. Brazil’s biofuel industry is not destroying the rainforest, its way down in the southeast. But it could change in the future. The government must encourage certification methods which distinguish between crops grown on rainforest land and crops grown on degraded and abandoned agricultural land. If palm oil is produced from a plantation grown in a rainforest, we need to identify that and weed it out of the market. It is happening. Unilever, the biggest consumer goods company in the world, has just announced, after pressure from Greenpeace, that it will clean up its supply chain for palm oil by 2015.

Oil palm plantation and logged-over forest in Borneo. Photo by Rhet A. Butler |

The market will react if there is a demand for them to do so. So we need to provide a market pull. The consumer must say, “I’m not buying bad palm oil any more. I’m only going to take good palm oil.” Pressure from NGOs like Greenpeace can help.

There is no sustainable palm oil in the world except from Colombia. How crazy is that? But it’s going to change. We now have the standards in place from the Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil (RSPO).

Governments can help by putting in regulations like FLEGT, an EU regulation that will be implemented starting in 2009 where illegally-bought timber will be excluded from the open markets. You have to prove the chain of custody on the timber at the borders of the EU. If you can’t prove it, the timber will not be allowed in. Now these are voluntary supply agreements between the EU and supplier countries.

The problem with FLEGT is if you are in Indonesia and send your wood to China where it is turned into furniture, then you get around the system. So a second piece of legislation — commonly called the Lacey Act — is being considered. This is legislation that is being pioneered in the United States which put the onus on the importer, not the supplier. So if you are an importer of wood into the United States, you have to prove that it was not bought illegally under the laws of the supplier country where it was cut. Now how do they know that? That is difficult. But that is their problem and if they get that wrong they can go to jail. That is really getting people scared. The same law was been introduced to the British parliament a few months ago. Governments are moving to squeeze unsustainably sourced goods out of the supply chain. That should also happen with agricultural products over time. But it takes a long time and of course they can go sell their goods somewhere else because in places like India and China the demand is increasing and there is less concern about sustainability or they don’t have the laws in place yet. So we need to encourage those countries also to take that into account. But it isn’t going to happen quickly.

Mongabay: It is also easier to put a flag on a log than a batch of soybeans or palm oil.

Andrew Mitchell: It is. There is pretty good timber tracking now. With the barcodes you can track the timber from the stump all the way to the store.

But with soybeans or palm oil it is extremely difficult. So with agricultural products, one thing that is being considered is certifying the farm, not the goods it’s producing. When you certify the farm, the farm agrees that whatever it produces will be done to these standards — that doesn’t change provided the farmer maintains those standards. People are also looking at things like nano markers, little tiny markers that you can put in foodstuffs to follow it through the system. This needs more research but take organic flour as another example. Organic flour is very diffuse, but you can track organic flour from where it’s produced in the Ukraine or Canada extremely accurately. I know farmers who actually fly from Canada to Liverpool to see their flour off-loaded on the docks, to know that it’s their organic flour and it has been delivered with the right standards. The importers can’t say, ‘Your flour is contaminated, so I’m lowering the price’. The farmer can say: ‘No, I’ve tracked it, I’ve followed it, I’ve produced it, don’t tell me you can lower the price’. That’s how the market works. So if you can track organic flour, which is very diffuse, I suspect you can track sustainable soy. Price is a powerful market incentive.

Mongabay: Are any of the proceeds from these market mechanisms going to flow back to the Global Canopy Program’s research efforts into understanding interactions between climate and forests?

Saving the world’s most recently discovered cat species in Borneo

Last year two teams of scientists announced the discovery of a new species of clouded leopard in Borneo. The news came as conservationists launched a major initiative to conserve a large area of forest on an island where logging and oil palm plantations have consumed vast expanses of highly biodiverse tropical rainforest over the past thirty years. Now a pair of researchers are racing against the clock to better understand the behvaior of these rare cats to see how well they adapt to these changes in and around Danum Valley in Malaysia’s Sabah state. Andrew Hearn and Joanna Ross run the Bornean Wild Cat and Clouded Leopard Project, an effort that aims to understand and protect Borneo’s threatened wild cats, which include the flat-headed cat (Prionailurus planiceps), marbled cat (Pardofelis marmorata) leopard cat (Prionailurus bengalensis) the endemic bay cat (Catopuma badia) and the Bornean clouded leopard (Neofelis nebulosa). |

Andrew Mitchell: The Global Canopy Program is a science-based organization. Part of our role is looking at what science says about the ways in which forests interact with the atmosphere. Everything begins with the science. So, as our idea of forests operating as a public ‘utility’ catches on, we need to know what that ‘utility’ is doing. In that case I would see more money going into research that looks into questions like what is the economic value of the hydrological cycle of the Amazon and the Guyana Shield: how much rain is produced, what is the role of the forests in it, who are the beneficiaries, and what is their willingness to pay for the services? This is a combination of biological and economic research.

Mongabay: It’s like research and development (R&D) for a company.

Andrew Mitchell: Yes, like R&D for a company. We are already running a pilot project in the Amazon on that and we are putting in a request for the UK government to fund that research. We are also working on a major project with the Brazilian Ministry of Science and the Ministry of Environment to set up forest observatories in the Amazon and the Atlantic rainforest of Brazil to see how biodiversity from the forest floor to the canopy creates these ecosystem services. For instance we’re planning to follow up Brazilian studies of the production of volatile organic compounds that the forest produces to help generate rain.

We have tried for 30 years to put a price on biodiversity, and no one will give us big money for biodiversity. But actually the value is not so much in the biodiversity, but in the service it produces. It is the service that has the value. We need to understand how biodiversity is creating that service, and that could generate I believe whole new value for biodiversity and forests in the future.

Related sites

Related articles

- Investors seek profit from conserving rainforest biodiversity

- Dell becomes carbon neutral by saving endangered lemurs

- Shift from poverty-driven to industry-driven deforestation may help conservation

- Prince Charles calls for rainforest protection to fight climate change

- Al Gore’s investment firm bets that rainforest conservation will be profitable

- U.S. climate policy could help save rainforests

- Investing to save rainforests

- Private equity firm buys rights to ecosystem services of Guyana rainforest

- Markets could save forests: An interview with Dr. Tom Lovejoy

- More on ecosystem services

- More on carbon finance

Special thanks to Tiffany Roufs for her help transcribing the interview.