Palm oil industry moves into the Amazon rainforest

Amazon palm oil:

Palm oil industry moves into the Amazon rainforest

Rhett Butler, mongabay.com

July 9, 2008

Malaysia’s Land Development Authority FELDA has announced plans to immediately establish 100,000 hectares (250,000) of oil palm plantations in the Brazilian Amazon.

The agency will partner with Braspalma, a local company, to form Felda Global Ventures Brazil Sdn Bhd. FELDA will have a 70 percent stake in the venture.

“As a start, 20,000ha in Tefe will be opened for oil palm planting. After that, between 3,000ha and 5,000ha will be opened yearly,” said Deputy Prime Minister Datuk Seri Najib Razak. “Felda wants to emulate Petronas as a global player,” he added, referring to Malaysia’s national oil company.

Wednesday’s announcement had been expected. Last month Najib said Malaysia would seek to expand its booming palm oil industry overseas. The country is facing land constraints at home.

Accordingly, Felda chairman Tan Sri Mohd Yusof Noor said the agency had been offered 105,000ha in Papua New Guinea, 45,000ha in Aceh on the Indonesian island of Sumatra, and 20,000ha in Kalimantan on the island of Borneo.

Palm oil and the Amazon

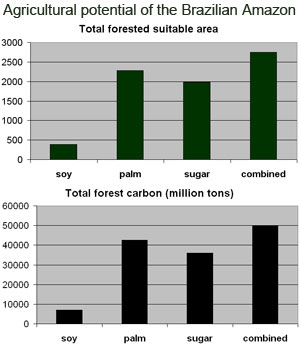

Agricultural potential for soy, palm, and sugar cane in the Brazilian Amazon (top). Carbon storage on forest lands suitable for various crops (bottom). Derived from the Woods Hole Research Institute’s Readiness For REDD: A Preliminary Global Assessment Of Tropical Forested Land Suitability For Agriculture. |

The establishment of oil palm plantations in the Amazon will be seen by environmentalists as a new threat to the world’s largest rainforest. Presently little commercial palm oil is produced in the region due partly to the traditional nature of Brazilian farmers and pest concerns, but the entrance of industry-leading Malaysian producers could serve as a model and quickly increase palm oil’s visibility as a viable form of land use. As the world’s highest yielding mass market oilseed, palm oil will likely offer better financial returns than cattle ranching and mechanized soy farms, the dominant agricultural activities in Brazilian Amazon, and will employ larger numbers of people (oil palm plantations may employ roughly one worker per 8-10 ha, whereas a single cowboy can handle 4,000-5,000 head of cattle grazing hundreds of ha of land).

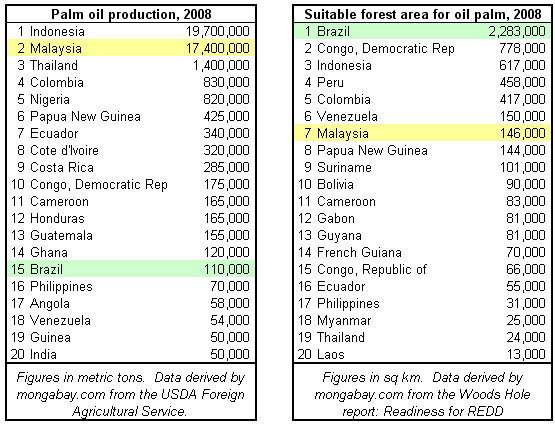

The potential for palm oil plantations in the Brazilian Amazon is vast: the Woods Hole Research Center estimates that 2.283 million square kilometers (881,000 sq miles) of forest land in the region is suitable for oil palm, an area far greater in extent than that which could be converted for soy (390,000 sq km) or sugar cane (1.988 million sq km). Woods Hole calculates this area of forest locks up some 42.5 billion tons (gigatons) of carbon in above-ground biomass, or roughly six times 2006 global emissions. Converting this area for palm would release nearly 60 percent of this carbon (oil palm plantations in SE Asia store about 75 tons of carbon per hectare).

Oil palm expansion in the Amazon will likely be facilitated by infrastructure projects currently underway in these region, including road-building, port expansion, and new hydroelectric projects. Oil palm producers may also benefit from a “logging subsidy” whereby timber harvested from a tract of land helps offset the cost of establishing a plantation. Before the recent run-up in palm oil prices, logging had been a key element to the profitability of oil palm plantations in Southeast Asia.

Palm oil economics

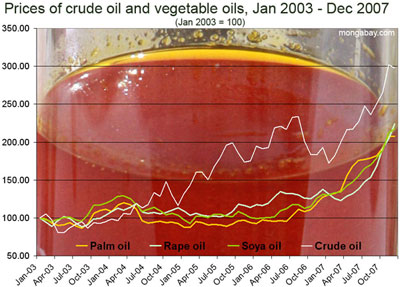

Market prices for crude and vegetable oils from January 2003 through December 2007. Data derived from FAOstat and the World Bank. |

The tripling of the price of palm oil since early 2005 has been linked to rising demand for crude oil, which has effectively driven up the price of all other vegetable oils. Producers in the U.S. and Europe have been diverting vegetable oils (canola/rapeseed and soy) and other agricultural feedstocks (especially corn) to the production of biofuels, buoying the high price for grains and oilseeds worldwide. While palm oil holds great potential as a feedstock for biodiesel production, prices are presently too high to make the process viable — roughly 80 percent of the cost of biodiesel is the price of its feedstock. As such most palm oil is currently used in food products, cosmetics, and for industrial purposes less than one percent of Malaysia’s 2007 production was used for biodiesel. Still the industry has high hopes to eventually use more palm oil as a biodiesel feedstock.

Palm oil and biodiversity

Oil palm plantations support significantly lower levels of biodiversity than even logged rainforests. Research by Lian Pin Koh and David Wilcove found a 77 percent decline in forest bird species and an 83 percent loss of butterfly species upon the conversion of old-growth forest to oil palm plantations. By comparison, secondary forest 30 years after logging retained roughly 80 percent of the original forest species. Oil palm plantations also store considerably less carbon than primary forests.

Reducing the impact of oil palm and other forms of agriculture in the Amazon

Oil palm plantations and heavily logged forest near Lahad Datu, Malaysia. Photo by Rhett A. Butler |

It may seem inevitable that large areas of Amazon forest will be converted for agriculture, but there are ways to mitigate the most serious environmental impacts of the transition. Developers can be encouraged to adopt cultivation methods promoted by the Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil — an industry-led initiative to improve its environmental performance. These include using natural pests and composting in place of synthetic pesticides and fertilizers whenever possible, implementing no burn policies, and creating catchment ponds to prevent palm oil mill effluent (POME) from entering waterways where it would damage aquatic habitats.

Better enforcement of existing Brazilian environmental laws — including requirements to leave a portion of one’s land forested and riparian buffer zones — coupled with Brazil’s real-time satellite monitoring of forest cover could further reduce the worst impacts of extensive palm oil cultivation in the Amazon.

Because oil palm plantations offer higher yields on a per hectare basis than either soy or beef production, the establishment of regulations that restrict new development to already cleared lands or secondary forests could result in a net economic gain for the region without the need to clear more forest. In a sense, if the highly productive oil palm plantations replace low-intensity cattle pasture already established in the region (without displacing ranchers or farmers into forest areas), the Amazon may well be richer economically and biologically. An important component to this would be the maintenance riparian zones and migration corridors along with the protection of critical habitats.

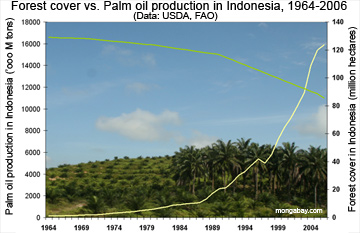

Forest cover versus palm oil production in Indonesia. In 2007 Indonesia overtook Malaysia as the world’s largest producer of palm oil. Together the two countries account for more than 85 percent of global production. |

Finally, ecosystem services payments, like those employed in a pilot program in the state of Amazonas, whereby rural communities are paid for leaving forests standing, could offer economic alternatives to forest clearing. If REDD (Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Degradation) and other payment schemes become a reality, they could compete directly with other forms of land use.

More data on palm oil production and use

(units = metric tons, 2008 market year)

| Palm Oil Food Use – Domestic Consumption | ||

| 1 | India | 4715 |

| 2 | Indonesia | 4231 |

| 3 | China | 4100 |

| 4 | EU-27 | 2715 |

| 5 | Pakistan | 2360 |

| 6 | “Other” | 1170 |

| 7 | Malaysia | 950 |

| 8 | Bangladesh | 945 |

| 9 | United States | 863 |

| 10 | Nigeria | 800 |

| 11 | Egypt | 740 |

| 12 | Iran | 550 |

| 13 | Japan | 512 |

| 14 | Russian Federation | 490 |

| 15 | Thailand | 480 |

| 16 | Vietnam | 470 |

| 17 | Colombia | 410 |

| 18 | Turkey | 410 |

| 19 | Burma, Union of | 375 |

| 20 | South Africa | 348 |

| Palm Oil Imports | ||

| 1 | China | 6200 |

| 2 | India | 4900 |

| 3 | EU-27 | 4050 |

| 4 | Pakistan | 2460 |

| 5 | “Other” | 1170 |

| 6 | Bangladesh | 1070 |

| 7 | United States | 960 |

| 8 | Egypt | 925 |

| 9 | Russian Federation | 620 |

| 10 | Iran | 550 |

| 11 | Japan | 550 |

| 12 | Turkey | 500 |

| 13 | Vietnam | 480 |

| 14 | Jordan | 460 |

| 15 | United Arab Emirates | 400 |

| 16 | Burma, Union of | 375 |

| 17 | Kenya | 350 |

| 18 | South Africa | 350 |

| 19 | Mexico | 335 |

| 20 | Iraq | 330 |

| Palm Oil Exports | ||

| 1 | Indonesia | 14800 |

| 2 | Malaysia | 13840 |

| 3 | Thailand | 500 |

| 4 | Papua New Guinea | 405 |

| 5 | Jordan | 300 |

| 6 | Colombia | 295 |

| 7 | United Arab Emirates | 220 |

| 8 | Singapore | 200 |

| 9 | EU-27 | 140 |

| 10 | Ecuador | 140 |

| 11 | Honduras | 122 |

| 12 | Sri Lanka | 115 |

| 13 | Costa Rica | 110 |

| 14 | Guatemala | 50 |

| 15 | Kenya | 30 |

| 16 | Benin | 27 |

| 17 | Cote d’Ivoire | 15 |

| 18 | United States | 15 |

| 19 | Brazil | 10 |

| 20 | Yemen | 10 |

| Palm Oil Industrial – Domestic Consumption | ||

| 1 | Malaysia | 2745 |

| 2 | China | 2100 |

| 3 | EU-27 | 925 |

| 4 | Indonesia | 720 |

| 5 | Mexico | 362 |

| 6 | Thailand | 350 |

| 7 | India | 210 |

| 8 | Egypt | 185 |

| 9 | Brazil | 180 |

| 10 | Nigeria | 177 |

| 11 | Bangladesh | 140 |

| 12 | Russian Federation | 130 |

| 13 | Colombia | 115 |

| 14 | Cote d’Ivoire | 110 |

| 15 | United States | 95 |

| 16 | Turkey | 90 |

| 17 | Congo, Democratic Rep | 73 |

| 18 | Pakistan | 70 |

| 19 | Costa Rica | 55 |

| 20 | United Arab Emirates | 40 |

| Palm Oil Production | ||

| 1 | Indonesia | 19700 |

| 2 | Malaysia | 17400 |

| 3 | Thailand | 1400 |

| 4 | Colombia | 830 |

| 5 | Nigeria | 820 |

| 6 | Papua New Guinea | 425 |

| 7 | Ecuador | 340 |

| 8 | Cote d’Ivoire | 320 |

| 9 | Costa Rica | 285 |

| 10 | Congo, Democratic Rep | 175 |

| 11 | Cameroon | 165 |

| 12 | Honduras | 165 |

| 13 | Guatemala | 155 |

| 14 | Ghana | 120 |

| 15 | Brazil | 110 |

| 16 | Philippines | 70 |

| 17 | Angola | 58 |

| 18 | Venezuela | 54 |

| 19 | Guinea | 50 |

| 20 | India | 50 |

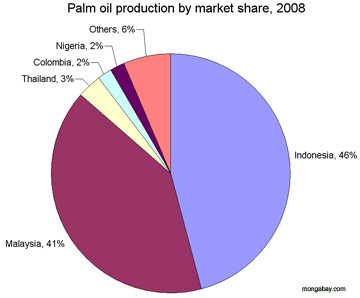

Chart/Graph: Market share of top 5 palm oil producers for the 2008 market year

More news on palm oil (full list of articles)