Birds face higher risk of extinction than conventionally thought

Birds face higher risk of extinction than conventionally thought

An interview with ornithologist Dr. Cagan Sekercioglu

mongabay.com

July 15, 2008

|

|

Birds may face higher risk of extinction than conventionally thought, says a bird ecology and conservation expert from Stanford University.

Dr. Cagan H. Sekercioglu, a senior research scientist at Stanford and head of the world’s largest tropical bird radio tracking project, estimates that 15 percent of world’s 10,000 bird species will go extinct or be committed to extinction by 2100 if necessary conservation measures are not taken. While birds are one of the least threatened of any major group of organisms, Sekercioglu believes that worst-case climate change, habitat loss, and other factors could conspire to double this proportion by the end of the century. As dire as this sounds, Sekercioglu says that many threatened birds are rarer than we think and nearly 80 percent of land birds predicted to go extinct from climate change are not currently considered threatened with extinction, suggesting that species loss may be far worse than previously imagined. At particular risk are marine species and specialists in mountain habitats.

Sekercioglu in Angola |

“Thousands of bird species are confined to tropical mountain forests which are shifting higher due to climate change,” he explained. “These bird species are also very sensitive to microclimate so their distributions will get narrower as they move up mountains in response to warming temperatures. Some will eventually run out of room, a phenomenon I call “the escalator to extinction”, a frightening “stairway to heaven”. This applies to other organisms as well, particularly less mobile species like amphibians or plants, but we have little data on the shifts that are happening in the tropics.”

“Over half of seabird species are already threatened or near threatened with extinction. This is double the rate of forest birds. Marine birds reproduce very slowly so are sensitive to adult mortality that results from getting caught on fishing lines when they try to get the bait. On top of that, their breeding colonies are vulnerable to introduced predators like cats and rats. And now they have to deal with rising CO2 levels that cause increases in ocean temperature and acidity, leading to shifts in sea birds’ feeding grounds.”

Sekercioglu believes that conservation efforts will be key to heading off a mass extinction among birds and other organisms. In particular, Sekercioglu says that conserving intact habitats and enhancing the capacity of human-dominated landscape — like tropical agricultural lands — to support biodiversity could sustain many species that would otherwise be lost due to changes in land cover.

Sekercioglu banding birds in Las Cruces, Costa Rica. |

“Agricultural landscapes provide a great conservation opportunity,” Sekercioglu told mongabay.com. “Tropical human-dominated landscapes should be better integrated into conservation programs rather than being considered hopeless. They also offer a great opportunity to restoration ecologists, both for research and for applied conservation.”

Sekercioglu — who runs three conservation research projects: in his native Turkey, Costa Rica and Ethiopia — says that such efforts must involve local people to be effective.

“Any conservation project needs to consider and involve local people,” he said. “Even without guaranteeing any financial benefits, you can get many local people to your side by treating them nicely, by emphasizing the global importance of their homeland, and by involving their stewardship.”

White-ruffed Manakin, one of the core study species Sekercioglu has radio-tracked intensively around Las Cruces, Costa Rica. |

He adds that ecotourism is one way the local communities can benefit from conservation.

“Ecotourism can be critical in involving local people as it can provide important funds if conducted at the local scale, it provides excellent opportunities for environmental education that can lead to jobs as nature guides, visitors coming from all over the world create international camaraderie, and the attention makes local people feel proud about their natural and cultural heritage.”

Sekercioglu discussed conservation and his research in a July 2008 interview with mongabay.com

An Interview With Dr. Cagan Hakki Sekercioglu

Mongabay: You were recently awarded the prestigious the Whitley Gold Award for your conservation efforts in Turkey. How did you go from being on a Wall Street career track to a bird expert?

|

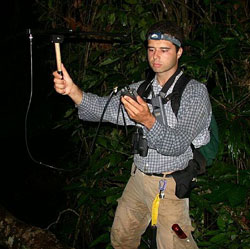

Sekercioglu radio tracking birds. |

Cagan Sekercioglu: I was not exactly on a Wall Street track but there was a temptation in the form of a job offer from a major investment bank that was seeking Harvard science majors with quantitative backgrounds and honors like summa cum laude. This was 11 years ago. Even though I now have a Ph.D. and am a senior scientist at Stanford University, I still have not reached the starting salary offered for that right-out-of-college job! But I do not regret it the least. My passion is to help save the world’s biodiversity while living a low-impact life. Doing cutting-edge science and community-based conservation in the developing world is far more meaningful to me than maintaining a high-consumption existence. A lot of wealthy people look for meaning, want to help the planet, and support conservation projects. The Whitley award is a perfect example of that. I am living many people’s dream.

I was always into birds and started birding in Istanbul when I was 15. At the time, there were fewer than 20 Turkish birdwatchers out of 65 million people. Still, there are only a few hundred. I did my undergraduate thesis on the long-term effects of selective logging on the birds of Kibale Forest, Uganda. Then I did my Ph.D. on the causes and consequences of bird extinctions, both in the field in the Costa Rican countryside and as part of a global analysis based on a database of world’s birds I created.

Mongabay: How is your research conducted?

Cagan Sekercioglu: I have four main projects.

Sekercioglu in the Brazilian Pantanal with colleagues Andras Baldi and Walter Jetz. |

The longest-running is the “Population dynamics of Costa Rican forest and countryside birds” project around Las Cruces, where I conducted my PhD research with Gretchen Daily and Paul Ehrlich. Mongabay has written about our radio tracking work there. Currently supported by Stanford University, National Geographic Society, the Moore Family Fund, and the Koret Fund, we combine a diversity of methods (mark-recapture using bird banding, radio tracking, GIS analysis, nest monitoring, isotopic and molecular analyses, vegetation surveys and microclimatic measurements) to study the ecology and long-term population dynamics of native bird species in forest vs. forest fragments and human-modified habitats. Primary objectives are to understand the birds’ use of forest fragments and other tropical countryside habitats, obtain measures of long-term population changes in different habitats, and advise locally-compatible habitat restoration policies that increase the viability of regional bird populations. Since 1998, we have mist netted over 50,000 birds of 250 species. In addition to banding the birds, we have radio-tracked over 450 individuals of 11 species, which to our knowledge, is the largest sample size of any tropical bird radio-tracking project in the world. We also monitor hundreds of bird nests to measure breeding success, investigate avian malaria and other blood parasites, use molecular biology to understand population connectivity, and use feather stable isotopes to understand bird diet and migration patterns.

In Turkey, my NGO KuzeyDoga directs a range of projects supported by the Christensen and Whitley Funds, UNDP, and the Conservation Leadership Programme. These include running the only bird banding (ringing) stations in eastern Turkey, doing wetland restoration, conducting the only ecological restoration experiment in the east by erecting cattle exclosures in important wetlands, using camera traps to study wolves, bears and other carnivores, and interviewing villagers for ethnobotany research. We collaborate with Kafkas University of Kars and 19 Mayis University of Samsun. Our focus is to build local capacity, train students and do applied conservation, while collaborating with a range of experts from scientific illustrators to dragonfly specialists. Details are on

www.kuzeydoga.org

Sekercioglu’s field assistants in Costa Rica |

In Ethiopia, also supported by the Christensen Fund, I run the Ethiopia Bird Education Project (to educate people, not birds!), which conducts environmental education and capacity building with everyone from primary school to graduate students to local people with no schooling. We are working to establish the official Ethiopian bird banding program, to be run by Ethiopians. To enable that, we are training Ethiopians to become licensed bird banders. We work with Ethiopian Wildlife and Natural History Society, the Debub University Awassa College of Agriculture and Wondo Genet Forestry College to study the bird communities of savanna woodland, shade coffee, montane forest, and wetlands with bird banding and bird surveys.

I also conduct meta-analyses on bird ecology, conservation and future extinctions scenarios by using the world bird ecology database I compiled from hundreds of bird books and articles with the help of students and volunteers. It has over 600,000 entries on a range of variables such as diet, habitat, clutch size, body mass, region and conservation status. Publications and further details of my research are on

www.sekercioglu.org

Mongabay: While you’ve worked all over the work, you’ve spent some time in Kars, Turkey, a region more famous for its frigid winters than its biodiversity. What’s it like surveying the bird life of Kars?

Sekercioglu in cold-weather gear in Hokkaido, Japan |

Cagan Sekercioglu: Kars is similar to Alaska in some ways. It is a wild place that can be -50 C in the winter, but between April-October, it is very pleasant. Even in the winter, it is a beautiful, snow-covered landscape where you can see foxes and wolves. Kars is mostly steppe grassland, wheat fields, and rangeland that is bisected by the Kars river and sprinkled with seasonal wetlands, ponds and lakes. It also has extensive yellow pine forests in Sarikamis. In the south, there is the more temperate Aras River valley, a Key Biodiversity Area with orchards. Kars is mostly a mile-plus high plateau but it can get up to 3000 m in the Allahuekber Mountains and below 1000 m in the Aras Valley. We work mostly at the Kafkas University wetland/grassland/river ecosystem, Sarikamis forest, Kuyucuk Lake, and the Aras River between Kars and Igdir. We run bird banding (ringing) stations at the latter two sites and do year-around bird surveys. We sometimes have to wade in waist-deep snow in the winter to count birds and, in August, it can be near 40 C at Aras, where we have to wear rubber waders to check the nets over the lake. At Kuyucuk Lake, we stay in a 9 square meter cabin with no shower and cook food over an LPG stove. The nets are checked every hour, 24 hours-a-day, with no days off for the entire fall and spring season. Although we rotate people, our core banding team works without a day off for three months in the fall and spring. We need more people but in Turkey there are only eight certified bird banders, including myself. However, our project is training dozens, educating hundreds, and building critical conservation and ecological research capacity.

Mongabay: What are the biggest threats to birds? What’s your outlook for birds over the next century?

Cagan Sekercioglu: Based on four complementary analyses I conducted with my colleagues, I estimate that about 15% of world’s 10,000 bird species will go extinct or be committed to extinction by 2100 with business as usual. Keep in mind that birds are among the least threatened of any major group of organisms (e.g. plants, mammals, amphibians, mollusks). Unfortunately, things are getting worse, so this number is likely to be higher, as many as 2 out of 5 bird species. Globally, habitat loss is the top threat. Climate change is becoming an increasingly bigger threat, and by forcing changes in species ranges, it exacerbates the effects of habitat loss (and vice versa). In our April 2008 paper in Conservation Biology, we predicted that up to 30% of land birds may go extinct by 2100 due to a combination of climate change and habitat loss. Most worryingly, 79% of bird species we predicted to go extinct are not currently considered threatened with extinction. This is because most of these species are endemic to tropical mountains where there is still quite a bit habitat, but it is very susceptible to climate change and resulting vegetation shifts.

Sekercioglu in the Malaysian rainforest |

Introduced species like cats, rats, dogs, pigs, snakes, and goats also comprise a huge threat, especially on islands. Feral cats and domestic cats allowed to roam outside kill birds everywhere. Hundreds of millions of birds annually are killed by free-roaming domestic cats in the US alone. We can stop this simply by keeping the cats indoors or at least neutering them and attaching a CatBibTM to them (I have no financial or other connections). Unfortunately, many cat owners keep finding excuses for the damage done by their cats, some keep feeding feral cats illegally (including on Stanford’s reserves), and some cat-lovers will attack any person who talks about the damage to wildlife done by cats. I am sure I’ll get some hate mail for saying these. Cats are not native to the US, 90 million domestic cats are simply an extension of humans, and ironically, the wild ancestor of the domestic cat, Felis sylvestris has disappeared from most of its former European range. If people truly care about cats, they should do a lot more to save the 36 wild cat species. All species’ populations are going down and 26 of them are threatened or near threatened with extinction.

Other major threats to birds include wild bird trade for exotic pets, seabird bycatch on fishing long-lines (especially tuna), hunting birds for food, and pollution, such as oil spills. The more we consume, the less room we leave for birds and other creatures on this planet.

Mongabay: What types of birds are particularly vulnerable to global change (i.e. climate change and habitat loss, modification, and fragmentation)?

Sekercioglu in his cabin at Las Cruces Biological Station, Costa Rica. |

Cagan Sekercioglu: Tropical forest, marine, grassland, and mountain birds, sedentary birds, slow-reproducing and specialized species, are especially vulnerable. Many tropical forest species, such as understory insectivores, are extreme habitat specialists, do not migrate, and will not leave forest even if it is very fragmented or it is pushed to the top of a mountain. Many birds species decline in and disappear from forest fragments as a result. Thousands of bird species are confined to tropical mountain forests which are shifting higher due to climate change. These bird species are also very sensitive to microclimate so their distributions will get narrower as they move up mountains in response to warming temperatures. Some will eventually run out of room, a phenomenon I dubbed the escalator to extinction, a frightening “stairway to heaven”. This applies to other organisms as well, particularly less mobile species like amphibians or plants, but we have little data on the shifts that are happening in the tropics. We also know little about most species’ actual distributions, even those of many birds, a group better known than most. With my colleagues Walter Jetz and James Watson, we have shown that many bird species’ global ranges (distributions) are overestimated. The overestimation increases for species that are more specialized, threatened, and narrow-ranging, meaning that these birds are rarer than we think and their extinction likelihoods are underestimated. Over half of sea bird species are already threatened or near threatened with extinction. This is double the rate of forest birds. Sea birds reproduce very slowly so are very sensitive to adult mortality that results from getting caught on fishing lines when they try to get the bait. On top of that, their breeding colonies are very vulnerable to introduced predators like cats and rats. And now they have to deal with rising CO2 levels that cause increases in ocean temperature and acidity, leading to shifts in sea birds’ feeding grounds.

Mongabay: What do you see as the best way to fund conservation efforts? How can local people be more involved in conservation? What is the role of ecotourism?

Cagan Sekercioglu: Sadly, very little of the vast amounts of money businesses and governments spend go to conservation. Conserving our ecosystems in collaboration with the local people that depend on them not only bring enormous financial benefits in the form of ecosystem services, but also increase global security by improving the livelihoods of millions of impoverished people, especially in the developing world. Insurance companies were among the first to realize the financial costs of climate change and corporations need to realize that funding conservation will help both their image and their bottom line, even if they do not care at all about living in a better, more natural, and healthier world.

A Fiery-billed Aracari, one of the tens of thousands of Costa Rican birds that have been banded by Sekercioglu’s team. Photo by Cagan Sekercioglu. |

Every person has a responsibility and even small amounts can add up and make a big difference. People should seek out and donate to locally-based NGOs doing effective work or to organizations that guarantee that the money goes directly to local communities and not to overhead. The Internet is playing an increasing role in this.

Local people are critical. Like all of us, they want a decent life and any conservation project needs to consider and involve local people. From my experience, I realized that simply explaining our objectives, listening to local people, and bringing them in as partners make a major difference. Rural people worldwide have experienced a lot of discrimination and condescension, and are often very humble and self-deprecating. They appreciate enormously when they are taken seriously and their input is requested. Even without guaranteeing any financial benefits, you can get many local people to your side by treating them nicely, by emphasizing the global importance of their homeland, and by involving their stewardship. Local and traditional knowledge is enormously valuable, but is rapidly disappearing.

Ecotourism can be critical in involving local people as it can provide important funds if conducted at the local scale and it provides excellent opportunities for environmental education that can lead to jobs as nature guides. The visitors coming from all over the world promotes international camaraderie and the attention makes local people feel proud about their natural/cultural heritage.

Mongabay: Do you have advice for anyone interested in pursing a career in conservation? (not necessarily as a scientist)

Radio-tracking Tangara icterocephala near Las Cruces, Costa Rica |

Cagan Sekercioglu: It is competitive to get a long-term job and you only see the highlights in documentaries. You have to be persistent, hard-working, and enthusiastic, like in any other field. It helps to get some formal training, especially in natural and social sciences related to conservation, but equally important is field experience. Volunteer, volunteer, volunteer for conservation and research projects as much as you can. If you get a volunteer position, work hard, do a good job, and do not act like you are doing the project a favor. There is a lot of competition for many volunteer positions and if you work to impress, those positions can lead to paying jobs or a good recommendation that can jump-start your career. Keep up good relationships with everyone, especially your former mentors, bosses, and collaborators and they will continue to help your career. It is a relatively small and connected field. Go to conservation meetings, as networking is important like any other discipline. You may not enjoy field work, as it can be demanding, tedious, and even dangerous, but you can still have a career in conservation. Business skills are increasingly in demand. The Natural Capital Project of our Center for Conservation Biology at Stanford University is a good example. So you can even help conserve habitats and species without ever leaving your office although there is no fun in that!

Mongabay: Where is your favorite place to work or visit?

Scale-crested Pygmy-tyrant (Lophotriccus pileatus) at Las Cruces, Costa Rica |

Cagan Sekercioglu: It is impossible to pick a favorite. I love the tropical forest because every day there is a new surprise. You can spend a lifetime and you will still see new species. It is very exciting to go out every day and be on the look out for something unusual. I am especially fond of tropical foothill forests and pre-montane forests because the diversity is still there, but it does not feel like a sauna and my photography and film equipment lasts longer before dying from humidity and/or fungus. I spent most of my career working in the pre-montane forests of Australia, Africa and Latin America. I am captivated by truly remote forests like in parts of Amazonia and New Guinea. As a climber, I love high mountains and have climbed up to 6310 m. It was the peak of Chimborazo, Ecuador, and happens to be the farthest land point from the center of the earth. I love the vitality, cultural diversity, and the color of Africa. But for sheer wilderness and beauty, it is hard to beat the Antarctic peninsula. It is like another planet.