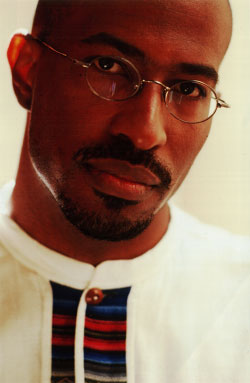

AN INTERVIEW WITH VAN JONES

AN INTERVIEW WITH VAN JONES

“The green movement has to become a rainbow-colored movement in order to be successful”

Maria José Viñas, special to Mongabay.com

June 23, 2008

Van Jones, a social and environmental activist, believes a greener economy not only could save the planet, but also must provide pathways out of poverty for America’s disadvantaged communities. A civil rights lawyer from Yale University, Jones started promoting the idea of “green-collar jobs” in 2005 through the Ella Baker Center for Human Rights in Oakland, California. In September 2007, he launched the “Green for All” campaign. Jones recently took time to share his perspectives with Mongabay.com.

Mongabay: The green-collar jobs initiative is a hot topic these days. The Democratic presidential candidates have cited it, and you and your organization have been promoting your campaign in many newspapers, radio and TV stations. But do you think politicians and the public have an accurate idea of what a green job is?

Van Jones |

Van Jones: Well, I think we are all still figuring out exactly what a green-collar job is. It’s a term that has captured people’s imaginations. Now everybody, from MIT to the Apollo Alliance to us, the Green for All campaign, are working to sharpen the definition. The current definition is that it’s a blue-collar job that is graded to better respect the environment. It’s a job where your wealth is not taking away from the communities or the planet’s health. Once you start trying to drill down, you have to decide how green is green, how much it’s going to be “green-washing” and what job is worth the name in terms of compensation, in terms of career, in terms of advancement options and benefits. So now the real work begins to refine the definition, and we’re excited about that.

Mongabay: And what’s your campaign’s current description?

Van Jones: For us, a green-collar job has to be a living-wage job and it has to be a real upper-mobility pathway. We don’t believe the country needs “solar sweatshop jobs” or a “Walmart wind industry.” We want to make sure that we have equal opportunity, which means creating real diversity from the beginning in this new economy. We want to make sure people have labor rights, so they can organize themselves and get the best possible deal. And we want to make sure these jobs represent an end to poverty.

Mongabay: How do we make sure the new jobs go to the people who need them the most?

Van Jones: The most important we can do is make sure that the job trainers have the extra support they need to engage people with disadvantages. Trying to get through a 12-week or a 6-month training program while worrying about what to put on the table can be very difficult, but there are methods — like child care — to help people get through these programs. And once they get through the training program, they start paying taxes, they pay back the investment. We really want to make sure that we go that extra mile to ensure that the green economy is a really inclusive economy.

Mongabay: Historically, people who oppose the green movement have said that environmentally friendly measures go against a strong economy. But you say you can reconcile both things.

Van Jones: What’s hurting the economy right now is the way we’re committed to a dirty, wasteful model of economic development. Look at our gas prices: Why are they going up? They’re going up because there are scarce resources and now everybody — India, China, and every other country in the world — wants these resources. And when the energy prices go up, all the other prices go up, because energy’s needed to make everything else. So for all these people who say we can’t have green this and green that because we’re destroying the economy, well, look at the economy now! We are already in bad shape economically because we didn’t do the transition earlier to energy conservation and cleaner, renewable energy. It’s the pollution-based economy that is economically not viable.

Mongabay: How is the alliance of the environmental and social justice movements different from other types of alliances, such as the alliance between environmental groups and businesses, or the alliance of environmental and Christian groups?

Van Jones: We need all of them; we need every alliance you can think of. Our view is that we have a tremendous opportunity here: We are primarily focused on people of color, low-income people and disadvantaged people. But the green movement has to become a rainbow-colored movement in order to be successful.

Mongabay: The people your initiative focuses on are less able to make environmentally friendly consumer choices, but now you’re telling them they can be environmentally friendly too.

|

Van Jones: My view on this is that people with the higher income tend to fly more airplanes, buy SUVs and lead high-consumption lifestyles. They are the ones who contribute a lot more to global warming and to environmental destruction. They’ll occasionally also go and buy eco-chic products, but it doesn’t offset that. Their net contribution is still pretty high to a lot of destructive stuff. So let’s be very clear here: poor people may not buy eco-chic products, but they don’t buy many other products at all. So they’re not really contributing [to environmental damage] very much. I think it’s more of a cultural question in the terms of the way that environmental issues are presented. They appeal to the affluent more than to the ordinary. That’s our challenge. We want to make sure that the message resonates with ordinary people: the people who don’t need a green economy as a place to spend money, they need a green economy as a place to earn money and maybe even save some of it.

Mongabay: Why do we need to bring low-income people into the environmental movement?

Van Jones: Everybody has to have a stake in the green economy. You’re going to have a backlash alliance between polluters and poor people if they are left out. Everybody we don’t bring into the green economy the polluters are going to organize and speak for and use against us. We saw that here in California with Proposition 87, the green energy ballot measure that went down to the sea because the message didn’t resonate with enough ordinary working Californians.

Mongabay: Why didn’t the message resonate with them?

Van Jones: Hollywood and Silicon Valley kept promoting the proposition as a solution for energy independence and climate change. But the polluters then came back and said that this tax would be passed to low-income people, to regular rate-payers and car drivers. And the measure failed. Now, if we had had more people speaking up for it, looking at how this clean energy tax on the companies was going to be used to create more green collar jobs, to clean up the air so that the kids don’t have asthma, to help weatherize our homes so that we paid less energy bills, then the measure would probably have passed.

Mongabay: What did actually happen?

Van Jones: The polluters would come and say “this is bad for the economy, it’s bad for poor people.” Then the environmentalists said “oh, but it’s good for several issues, it’s good for the polar bears, it’s good for the rain forests, it’s good fifty years from now.” And what we had to say was “no, no, these things are all very important, but it’s also good for your pocket right now.” The “Green for All” is a popular message: “Hey, everybody can and should benefit from a green economy, in the future and right now.”

Mongabay: Do these green collar jobs consist only of installing and manufacturing jobs or are there career opportunities too?

Van Jones: There are career opportunities even within installation: you can move up to be a crew leader, and even the owner of a company yourself. So the opportunity has big impact as we hopefully begin to bring back green manufacturing jobs to the US.

Mongabay: What are the keys of success for the Green Collar Jobs campaign?

Van Jones: Mainly we need the government to help the green job creators. Our solar industry, our wind industry don’t get anywhere near the subsidies and support that the oil and coal polluter organizations get. That needs to be fixed. And then the green jobs trainers need to be helped too, the community colleges, vocational schools, all the people who train people for the job. They need to get money and support.

Mongabay: Will these jobs be created spontaneously by the market forces alone?

Van Jones: Markets will do the bulk of the work, but no serious industry in the U.S. has gone anywhere without the help of the government. From the railroads to the nuclear power to the internet, the government has to be involved and play an appropriate role and that’s really true here. The rules the government has written make it harsh for the clean energy to come forward.

Mongabay: Your campaign coordinates very diverse groups: environmentalists with labor unions, politicians, business executives… how easy it is to work all together?

Van Jones: The idea of green-collar jobs tends to bring up the best in people. Often people from the government, from labor unions, from the businesses, people who work with community centers for young people, they had never met in a conversation where they are trying to create something together. When they met, they had to fight about something. This is an opportunity for people to say “hey, we have to come together and co-create an opportunity here for our community.” This brings out incredibly creative thinking for the long-term good of the community.

Mongabay: Could you give me an example of that?

Van Jones: It happens all the time: in Oakland, Seattle, Minneapolis… everywhere we go we are lucky that we have the chance to meet in the same room with someone from the utility company and someone with the community college. It will emerge that the utility company is going to have to replace 50% of their workers in the next few years because baby-boomers are all retiring and they don’t know how to do it. Meanwhile, the people in the community college don’t even know that the company has that kind of need for workers. While the utility company not only needs to increase the number of workers, they also need to increase the quality of workers because of the new green technology. So suddenly there’s an opportunity for these two energies to work together.

Mongabay: Can you think of any case where this has happened?

Image courtesy of Solar Richmond |

Van Jones: In Richmond, California, there’s this program, “Solar Richmond”, which is a great model for training disadvantaged people to become solar panel installers. They go to do a 9-week program in construction that includes solar panel installation. Then they finish and they have a job ready from all the growing solar companies, so they’re able to fight pollution and poverty at the same time.

Mongabay: Does this program in Richmond include all the extra help you said that is needed to engage low-income people?

Van Jones: Well, they’re raising the funds to do that, that’s one of the things they’re most focused on. We’re hoping we can bring together pieces from other programs across the country to make this the best training program we know about and focus it on the green economy.

Mongabay: How successful have you been in drawing in the private sector — private employers willing to train and employ green collar workers?

Van Jones: We have 14 private employers — from solar to organic food industries — signed up in Oakland who are willing to take people on when they start graduating from the Green Jobs Corps. We constantly get calls from people who are willing to hire. The challenge right now is at the other side of the equation, getting the job training organizations funded so that they can start doing the training.

Mongabay: When will the Oakland Green Jobs Corps’s first cohort graduating?

Van Jones: They start this summer, so they should be graduating in the fall. It’s a three-month program, and they’re still going through the request for proposal process to get it completely sorted out.

Mongabay: How strong do you think the presidential candidates are in their support of the campaign?

Van Jones: Senator Obama has been very strong and passionately outspoken for the Green Jobs campaign. [Senator John] McCain has been obviously less so, less understanding of the important role of government engagement. The free market by itself is not going to solve the problem, because market works according to rules and the rules are written by the government. Right now the government’s rules don’t make sense. We haven’t changed the rules of government to spark a green economic renaissance, and it won’t happen by itself.

Mongabay: Are you afraid that the economic recession could slow down the creation of these jobs?

Van Jones: Well, the only way to get the economy going again is to have this massive green stimulus. We have to get back to a cheap energy economy, we can’t drill and burn our way out of our present economic and environmental problems. We have to invent and invest a way out of our problems, by moving into clean energy and energy conservation.

Mongabay: The first chapter of the Green Collar Jobs campaign was written in 2005 with your “Reclaim the Future” initiative. What are the main changes that have happened since then?

Van Jones: In 2005, if you googled the words “green collar jobs”, you would have gotten about probably 17 hits. Now you get 4,580,000 hits. That’s the definition of a change in conversation.

Green for All

Solar Richmond

Van Jones

Maria José Viñas is a graduate of the Science Communication Program at the University of California, Santa Cruz, and a science reporting intern at the Chronicle of Higher Education in Washington, D.C.