Food miles are less important to environment than food choices, study concludes

Food miles are less important to environment than food choices, study concludes

Jane Liaw, special to mongabay.com

June 2, 2008

|

|

Shoppers concerned about the environment should not place “buying local” at the top of their list of priorities when purchasing food, according to a study published online on April 16 in the journal Environmental Science & Technology. The fuel burned in transporting food items from farm to marketplace creates just a small percentage of the total greenhouse gas emissions associated with the food. Instead, consumers should shift their diets to include more foods that require less energy to produce in the first place.

Buying edible products with low “food miles”—the distance that food must travel to reach the consumer—is a growing movement among the environmentally conscious. These consumers patronize farmers’ markets in their neighborhoods to ensure the foods they eat were not transported long distances. A short trip from the farm to the consumer’s plate means less environmental damage, or so the conventional wisdom goes.

However, engineers Christopher Weber and H. Scott Matthews of Carnegie Mellon University in Pittsburgh have found that although most foods in the U.S. are transported over long distances, the process of making the food dominates greenhouse gas emissions. Indeed, they traced 83 percent of the average household’s food-related footprint of greenhouse gases to the origins of the food itself. Transportation only contributes 11 percent of greenhouse gas emissions on average—with the transportation leg from producer to retailer accounting for just 4 percent.

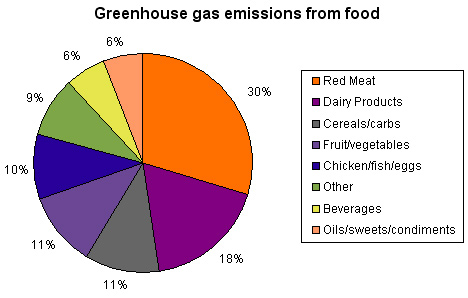

The start-to-finish process of raising and distributing red meat causes more greenhouse gas emission than any other food group, with dairy products coming in second. Animal products create the greatest amounts of nitrous oxide, emitted as a result of soil fertilization and management, because animals are inefficient at using plant energy. Producing red meat and dairy also causes the bulk of all methane emissions, which are put out by ruminant animals and manure fertilizer. Lower on the greenhouse gas emission scale are non-red meat protein sources such as chicken, fish, eggs and nuts, as well as fruit and vegetables.

The authors concluded that even small shifts in an average household’s diet from more greenhouse gas-intensive foods to less greenhouse gas-intensive foods would reduce that household’s food-related greenhouse gas emissions as much as eating entirely local products. For example, the authors found that replacing just 21 to 24 percent of red meat in the diet with chicken or fish would cut out as much greenhouse gas as buying all-local.

“Few papers are doing what these authors have done,” commented Richard Pirog, associate director of the Leopold Center for Sustainable Agriculture at Iowa State University. Pirog said the Carnegie Mellon scientists looked at a more complex part of the food life cycle than most other researchers have attempted. Most analyses have examined single food items, such as apples or lamb, or a small set of items; Weber and Matthews looked at the total life cycle of greenhouse gases emitted to produce the food consumed by an average household.

In recent years, the U.S. has imported a growing percentage of its food from other countries. Globalization often adds large distances to a food item’s journey to the consumer; from 1997 to 2004, the average distance covered by food increased by about 25%, from 6760 kilometers to 8240 kilometers. One might expect greenhouse gas emissions to be much higher as a result. However, ocean shipping represents more than 99 percent of total international shipping, and ocean shipping uses much less energy than trucking. So, the study concluded, globalization of the food market has only increased greenhouse gas emissions by 5 percent. Transportation still has much less impact on the climate than producing the food itself.

Weber was not surprised by the relatively small impact of transportation, but he was surprised by the extent to which this was true. “I was expecting maybe 10 percent, not 4 percent,” he said.

Though Weber and Matthews created a holistic model that includes all greenhouse gas emissions in food supply chains, Pirog noted that their study only looked at greenhouse gases. These gases are just one environmental consequence of any supply chain, he said. Other burdens include impact on water quality, acid rain, noise pollution, and smog.

“Food miles are an inadequate way of assessing environmental impact,” Pirog said. “People resonate with it because it’s easy to understand… but it was never meant to be some proxy for environmental impact.”

Pirog emphasized, however, that this study “is significant as being one of the first peer-reviewed papers in the U.S. from the life-cycle community that focuses on local foods.”

Weber said the holistic model can be applied to any products in the U.S. economy. The team’s next step is to do a whole economy assessment, calculating the part played by transportation in the life cycle of goods from all sectors. “Wood products, for instance, are not energy-intensive to make, so transportation is a large portion of wood furniture impact. Iron and steel are very energy intensive to make out of raw iron ore, so transportation is a small part,” Weber said.

He stressed that their food miles study should not dissuade consumers from buying local foods. “Both myself and my coauthor believe there are many good reasons to buy locally, such as supporting local agriculture,” Weber said. “A lot of people say local food is fresher and better-tasting. But given the choice, for the average consumer, buying local is not as important as what you eat.”

Jane Liaw is a graduate student in the Science Communication Program at the University of California, Santa Cruz.