Defaunation, like deforestation, threatens global biodiversity

Defaunation, like deforestation, threatens global biodiversity:

Interview with Rodolfo Dirzo, ecologist at Stanford University>

Rhett A. Butler, mongabay.com

May 20, 2008

|

|

Loss of wildlife is a subtle but growing threat to tropical forests, says a leading plant ecologist from Stanford University.

Speaking in an interview with mongabay.com, Dr. Rodolfo Dirzo says that the disappearance of wildlife due to overexploitation, fragmentation, and habitat degradation is causing ecological changes in some of the world’s most biodiverse tropical forests. He ranks defaunation — as he terms the ongoing biological impoverishment of forests — as one of the world’s most significant global changes, on par with environmental changes like global warming, deforestation, and shifts in the nitrogen cycle.

“Climate change is very important and well-known form of change, but there are others, including land use change [and] fragmentation” he said. “Those environmental changes affect biodiversity quite significantly.”

“Of all the global environmental changes, the most critical is biological extinction,” he continued. “For one thing, biological extinction is the only irreversible global environmental change that we can think of. Climatic change, given time and willingness on behalf of governments and society, is something we can fix. It will take time but is reversible.”

Rodolfo Dirzo |

Studying plant and animal interaction in the forests of southern Mexico’s Los Tuxtlas, Dirzo has seen firsthand some of the impacts of the loss of key pollinators and seed dispersers.

“When you have the situation that the mammals are not present you don’t even notice it, since most mammals are secretive or nocturnal. You tend to think that these forests are in good shape but overlook the fact that something very significant, the fauna, is missing. The absence of these animals indirectly affects the ecology of the forest,” he explained.

“Imagine that you were to remove all of the bats from the tropical rainforest. Then many of the plants that rely upon them as pollinators or as dispersal agents for seeds are going to be in trouble. This is relatively straight forward, but it is a little more difficult to think about what happens when the deer, the peccaries, and the tapirs are not there. It’s not easy to imagine that they are performing a service to the ecology of the forest, but in fact they are by trampling and preying on seeds and leaves. They are determining the structure of the understory which effectively determines the future of the forest — the impact of mammals on the forest understory is crucial: baby trees will someday grow up to become the forest canopy.”

Dirzo says the scale of defaunation is quite dramatic — each year tens of millions of animals are killed in the Amazon, Africa, and Asia. But he stresses the fact that local populations need to feed themselves, either by hunting or selling meat to markets. As such addressing defaunation will require addressing rural poverty — it will not be a simple as putting a fence about forest reserves or reintroducing captive animals to the wild.

He says that payment for ecosystem services like systems currently in place in Costa Rica and Brazil; agroforestry farming techniques; and smarter management of land could help improve the lives in people living in and around forests where much defaunation takes place. Education and conservation are also important components of campaigns to reduce the over-harvesting of wildlife.

AN INTERVIEW WITH RODOLFO DIRZO

Mongabay: How did you become interested in what you do now?

Rodolfo Dirzo: I was born in Mexico and studied plant ecology at the State university in Morelos, which is south of Mexico City. At the university I did a study mapping the vegetation coverage of an area north of Mexico City, which is an important watershed. The study was an eye-opening experience in that it showed the importance of the ecology for maintaining reservoirs for the city. It was also a great example of how ecology is tied to a practical, real-life problem—water conservation.

After my undergraduate work I went to work at UNAM with a prominent tropical professor of tropical ecology, Professor José Sarukhán, who has done a lot of work with tree demography and developing the field stations of Mexico like Los Tuxtlas. I worked in his lab for a number of years and then we decided it was time to go out to do my graduate training. At the time, which was the late 1970s, Mexico did not have a graduate program with a particular emphasis on ecology, so most of us plant ecologists had to leave the country to train. I went to the U.K. to the University of Wales, Bangor. At the time, the late 1970s, the University of Wales was the “Mecca” of plant biology in part due to John Harper, one of the most influential plant ecologists of contemporary times.

Even before I went to Wales I knew I wanted to do my research on ecological and evolutionary perspectives of interactions between plants and animals, asking the question, “To what extent are animals an important ecological and evolutionary force for plants?”

Rodolfo Dirzo |

My interest was to eventually go back to Mexico to apply that conceptual framework to local ecosystems. When I finished up my training in the U.K. in the early 1980s I did just this. This field was almost completely unknown in the country so I was lucky to attract students. So we developed a line of plant and animal interaction research particularly using the Los Tuxtlas research station as our laboratory to understand the evolutionary ecology of those interactions. I began to compile the most detailed analysis of herbivory—the patterns of consumption of plant tissue by animals—in tropical Mexico. I looked at a variety of questions: How much leaf area is eaten by animals? How does herbivory vary across species and according to the stage of the plant (e.g., baby plants versus mature plants)? How does it vary with the stratification of the forest? To what extent is herbivory different between the understory and the canopy, and if there are differences, what are the forces that might be underlying these differences?

When I was doing those studies in the 1980s and early 1990s it was very obvious to me that the most important interaction was insect herbivory and plants responding to that pressure, producing defensive compounds against insects. I wrote a paper in La Revista de Biologáa Tropical, a publication from Costa Rica, about patterns of herbivory in tropical forests such as Mexico. I concluded the paper noting that most of the herbivory I see in tropical forests was done by insects and discounting the significance of mammals. I wrote that “perhaps mammals are not much more than a decoration of the tropical forest in terms of this ecological interaction.” This is interesting because today I think that was a terrible mistake. I’ve been studying the interaction of plants with mammals — mammals as herbivores and in terms of being an ecological and evolutionary force for the plants. The reason why I came up with that conclusion now has become a very important aspect in my line of research: many tropical forests lack evidence of mammalian herbivory due too that what I call defaunation—the loss of the fauna. In turns out that everything I saw in terms the herbivory of plants by animals was with insects for the simple reason that mammals are not present there.

Monkey captured by hunters |

So in the early 1990s I wrote a paper about defaunation. My idea was to convey to the public that just as we talk about deforestation—a term that everybody understands and has a mental image of the meaning—to use an equivalent term, defaunation, to convey that there’s more than what we see with satellite imagery showing forest cover. What is missing from analyses of tropical forest conservation is the zoological impoverishment of forests due to human activities. You only see this impact when you continuously visit the forest on the ground and look at plants and analyze animal footprints and do animal transect surveys for year after year. Then you begin to see that, in addition to deforestation there is another serious problem in these ecosystems — the loss of the fauna, particularly the medium and large animals that are the most vulnerable because of hunting or habitat reduction or fragmentation.

As I said, my main interest has been to understand the patterns of herbivory, but my original results were biased by the absence of mammals doing the things that they should be doing in the forest, like eating plants, trampling, defecating, and preying on seeds. So when you have the situation that the mammals are not present you don’t even notice it, since most mammals are secretive or nocturnal. You tend to think that these forests are in good shape but overlook the fact that something very significant, the fauna, is missing. The absence of these animals indirectly affects the ecology of the forest.

Imagine that you were to remove all of the bats from the tropical rainforest. Then many of the plants that rely upon them as pollinators or as dispersal agents for seeds are going to be in trouble. This is relatively straight forward, but it is a little more difficult to think about what happens when the deer, the peccaries, and the tapirs are not there. It’s not easy to imagine that they are performing a service to the ecology of the forest, but in fact they are by trampling and preying on seeds and leaves. They are determining the structure of the understory which effectively determines the future of the forest — the impact of mammals on the forest understory is crucial: baby trees will someday grow up to become the forest canopy. My first paper on Defaunation looked at this — the idea of the “empty forest” was effectively popularized by the great tropical ecologist Kent Redford in his famous paper in Bioscience —.

Rodolfo Dirzo |

Biologists are preoccupied with the extinction of species and populations. I think this is a very well-justified concern, but I am much more worried about the extinction of ecological processes, which is another angle to the conservation of tropical ecosystems. To what extent are we losing, at least locally, ecological processes that are really critical in the structure and maintenance of the forest, but also in terms of maintaining the biological diversity of the forest. We talk about tropical forests being so important for their biological diversity but it seems to me that we need to pay attention to the extinction of ecological processes— what I gather from my ecological studies is that losing some of the components of the biological diversity affects the very processes that determine biodiversity. Biological diversity is to some extent maintained by the ecological interactions between plants and animals.

Mongabay: Can you give an example of an ecological process that is disappearing in some forest sites?

Rodolfo Dirzo: In my case, the obvious example is herbivory, the consumption of leaf tissue on the part of animals. On average if you measure how much leaf area is taken by animals, it’s about 10 percent in most tropical forest sites that have been studied. That’s looking at plants at the mid-stratum level. If you look at the plants in the understory, which are the plants that are going to regenerate the trees of the forest, the incidence of herbivory is similarly low; I have suspected that levels of herbivory in the understory should be higher: I imagine the impact of the removal of all the tapirs, peccaries, deer is partly responsible of such low herbivory— the loss of all of the animals that should be feeding on foliage in the forest. If you remove those animals, you may be removing an important control agent of the understory. This way, the plants upon which those animals typically feed are going to dominate locally in the understory. Thinking about the future, if that understory continues to be dominated by the few species that should be controlled naturally by these herbivorous animals, then you can predict and subsequently simulate with modeling that the forest of the future is likely to be affected by the absence of the animals. The loss of these animals, which are essentially the control agents of the understory, can bring about the local extinction of ecological processes such as herbivory.

Severed monkey leg in the bottom of a canoe in Gabon. Photo by Rhett A. Butler |

The impact of the loss of animals in the tropical forest extends beyond herbivory. Mammals not only take foliage, they also trample—which is an important control of the structure and diversity of the understory; and predate on seeds. Many tropical trees produce large seeds—like the size of a potato. A small rodent like a mouse or rat will not be capable of eating that seed. If the seedlings are not eaten by animals such as the tapir, peccary, and deer, the seedlings that emerge from these large seeds are going to dominate the understory.

Defaunation by humans tends to be a very selective process, where medium and large animals are the most hunted, while the small animals are ignored. Larger animals also tend to be less resistant to fragmentation and deforestation than the smaller ones. The situation that develops is that in the absence of the medium and large mammals, large seeds will not be eaten and therefore will dominate the understory, while seeds eaten by small rodents (the least impacted by fragmentation) will face heavy predation pressure. Such selective defaunation creates a new selective force for evolution of the forest: no attack on the large seeds, and heavy attack on the small seeds. In other words, humans are altering the structure and composition of the forest merely by hunting. So we can see, defaunation is a very serious problem.

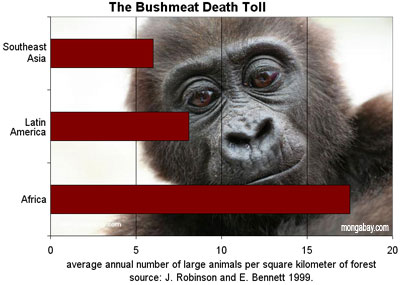

Southeast Asia (2 studies), 17.5 animals in Africa (2 studies), and 8.1 animals in Latin America (5 studies) according to data derived from J. Robinson and E. Bennett, Eds., Hunting for Sustainability in Tropical Forests (Columbia University Press, New York, 1999). Chart and photo of a young gorilla in Gabon by Rhett A. Butler. |

The loss of large animals that are the primary seed dispersal agents — particularly of tree species that have large fruit, sometimes with large seeds, — also has an important effect. Removing monkeys or large birds, for example, brings about a selective defaunation phenomenon that has a selective impact on the plant community. Now you have the opposite situation. Without the big animals to eat the large fruits, these are not dispersed, leading to a failure in the dispersal of the big seed species. Those seeds will tend to fall, without being dispersed, and may accumulate on the ground near their parent trees. That compounds the problem: large seeded species accumulate; these are the ones that go uneaten also in the absence of the large understory mammals, and whose seedlings escape herbivory in defaunated forests. This creates a complex cascading effect in which the forest changes its plant composition, diversity and regeneration patterns — all driven by anthropogenic defaunation!

Tapir. Photo by Rhett A. Butler. |

The situation of defaunation globally is very dramatic. Places such as the Brazilian Amazon have defaunation rates of about 15 million animals per year for a given locality. That repeats itself in Africa and Asia.

In the particular case of my study site—southeast Mexico—the situation is extreme. Animals the size of the peccary and larger have been completely hunted out of many sites.

I consider defaunation another global environmental change, on a level comparable with climate change, land use change, and fragmentation. Currently my group, including Brazilian visiting scholar Mauro Galetti (State University of Sao Paulo), postdoctoral associate Eduardo Mendoza and graduate student Camila Donatti, and me, are examining the ramifications of defaunation in tropical forests of Mexico and Brazil.

Mongabay: In 2003 you co-authored a review on extinction with Peter Raven of the Missouri Botanical Garden. Can you highlight some of the key points?

Rodolfo Dirzo: One of the major conclusions was that global environmental change was not only climate change. Of course climate change is very important and well-known form of change, but there are others, including land use change; fragmentation, which is the change in the spatial configuration of the forest. And those environmental changes affect biodiversity quite significantly. Perhaps the important corollary to the paper I wrote with Peter Raven is that of all the global environmental changes, the most critical is biological extinction: For one thing, biological extinction is the only irreversible global environmental change that we can think of. Climatic change, given time and willingness on behalf of governments and society, is something we can fix. It will take time but is reversible.

Wild bearded pig in Borneo. Pigs are widely hunted and an important food source in Indonesia.

|

What is completely irreversible is the loss of populations, species, and ecosystems. And I would like to emphasize that extinction takes place at these three levels. It is not only species extinction—which is what everybody knows about and thinks of when you talk about extinction. But I suspect that the most critical part of biological extinction is at the moment taking place at the level of populations, and we try to highlight this in our paper. For example, species might have a wide distribution. If there is intense deforestation in southeast Mexico and a species tree is locally eradicated, some might dismiss it, saying ‘Don’t worry because that tree occurs further North in Los Tuxtlas and further south in Costa Rica’. But really we are losing an entire evolutionary line of that species. In many cases we know that species that have a large distribution are composed of populations with different genetic types, sometimes making the population almost as different as if they were distinct species. Population extinction rates are likely much higher than species extinction rates.

There was another point which connects with the different types of global change: land use and overexploitation are driving local extinction of plant and animal species.

Now what can we do about that? It’s really a complex situation. On one hand, habitat fragmentation has a very important connection to defaunation. Forest remnants are incapable of maintaining viable populations of many medium and large animals. Another element is that by fragmentation areas that were once more or less remote are now more accessible to hunters. In other words, fragmentation exacerbates hunting pressure.

Mongabay: What are the approaches for slowing defaunation?

Rodolfo Dirzo: One strategy would be to reconnect fragmented habitats. Just as we talk about reforestation we could talk about refaunation. Technically there are a number of difficulties that we ecologists need to be working on. For example, a refaunation program at my study site at Los Tuxtlas would face these technical questions: Where do we bring the animals back from? Do we bring them from Chiapas? Costa Rica? There may be genetic differences between distinct populations of the same species. The second big issue is quarantine. How do we ensure that if we bring animals back, we do not unleash an epidemic disease. Third, and most critical, is that any reintroduction will fail if the local community is not involved. Without informing local people of the program, engaging them and having them appreciating the relevance of a refaunation program, the re-appearance of more animals might just drive more hunting. We need to combine reintroduction with a very strong program of involvement of the local communities—why the harpy eagle, tapir, and bat are important and should not be hunted. We need to articulate the concrete local benefits from converting an empty forest to one with all of its flora and fauna. People need to eat and have a dignified life. People need to be compensated for the giving up their needs or rights to hunt and exploit the forest and for their efforts to maintain biodiversity. Payments for environmental services—like the payment system in Costa Rica—may be one vehicle for compensation.

Despite a multi-decade ban on lemur-hunting in Madagascar, the primates are still trapped and shot in remote areas. Photo by Rhett A. Butler. |

In Los Tuxtlas, cattle ranching is the predominant driver of land use change, but it leaves a biologically impoverished landscape. In an agroscape of cattle grasslands basically we’re talking about an ecosystem that features a few species of grass — including some exotic grasses, imported from Africa—and one domesticated animal, the cow. Productivity is low—we’re talking less than 1.5 head per hectare. This is a very inefficient use of land, given the potential value that ecosystem services can provide. All you have to due is look at the erosion where forest has been cleared. Run off of light volcanic soils near Catamaco has caused sedimentation of the lake which in turn, affects fishing, an important source of food. Therefore it makes perfect sense to me that we should be looking at other types of management instead of extensive cattle ranching.

Agroforestry can maintain vegetation biodiversity, prevent erosion, and diversify income. Mimicking the structure of the rainforest using economic species—fruit trees, bananas, coffee, cacao, and timber species—can improve the well-being of local communities. For example, the canopy strata could be made of valuable timber trees; the medium strata of fruit trees; the understory of cacao and coffee; and a lower understory of decorative palms, orchids, and vanilla. It’s just a matter of organizing a system for land use. It could include areas that have been heavily impacted and intensively managed by the farmers.

In the Yucatan Peninsula there is an encouraging example in the Forest Pilot Program in Quintana Roo, which is focused on exploiting timber on a sustainable basis. The program, which is run as a cooperative of local farmers, has a rotational system where they use one piece of forest and only harvest trees of a given size. Using some technical assistance, they know how long it takes for the forest to regenerate harvestable timber and replant the trees they remove. It proves to be a very efficient system of forestry management and shows it can actually be profitable to sustainably harvest trees in this mosaic. The program promotes secondary products including furniture which have a higher value than the raw timber.

Mongabay: What about intensification, for example, going from 1 head of cattle per hectare to six? What about iguana farming or some way to augment the availability of protein using native species that are better adapted to the local environment?

Rodolfo Dirzo: People have looked at peccaries which can be managed more intensively. Iguana is another possibility—Panama is doing this. Certainly that can be done.

Agouti nursing her young in Belize. Agouti and related rodents play an important role in seed dispersal but are widely hunted. Photo by Rhett A. Butler. |

Intensification, by definition, would be a way to prevent the extensive conversion of land but we have to be careful about what it takes to intensify production. Increased use of fertilizers and high densities of animals can cause other problems. I think the root of the solution lies in a combination of different approaches—a mosaic of activities including agroforestry programs and some degree of intensification of cattle ranches. Also, another very important piece of management is maintaining pieces of forest because these sequester carbon, prevent erosion, and house biodiversity.

Mongabay: Are you seeing more commercial hunting now? Hunting for markets rather than subsistence?

Rodolfo Dirzo: Yes, there is both subsistence and commercial hunting. Most commercial hunting is illegal, but it seems to be increasing. The availability of weapons makes hunting easier.

There is also the market for live animals for consumption and the pet trade. For example the Peruvian town of Iquitos has a remarkable diversity of animals in its markets—both live animals and skins. Between 1982-1986, 1.4 million animals or animal skins were exported just from Iquitos.

Finally we have the removal of animals for biomedical research.

The take home point is satellite images don’t show defaunation. When you visit these forests it is really shocking to see the intensity of animals being harvested. It’s not just that these animals are charismatic—we now know that they play a critical ecological role in the health and structure of the forest and community as a whole. Defaunation is becoming a critical biodiversity conservation issue.