Carbon market could fund rainforest conservation, fight climate change

Carbon market could fund rainforest conservation, fight climate change:

Interview with Tracy Johns, REDD policy expert at WHRC

Rhett A. Butler, mongabay.com

May 19, 2008

A mechanism to fund forest conservation through the carbon market could significantly reduce greenhouse emissions, help preserve biodiversity, and improve rural livelihoods, says a policy expert with the Woods Hole Research Center (WHRC) in Massachusetts.

In an interview with mongabay.com, WHRC Policy Advisor and Research Associate Tracy Johns says that Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Degradation (REDD), a proposed policy mechanism for combating climate change by safeguarding forests and the carbon they store, offers great potential for protecting tropical rainforests.

“Past efforts to save tropical forests have relied on voluntary funding, and this simply has not been enough to properly value all of the benefits tropical forest provide, or to make their protection a competitive option compared to their destruction,” Johns explains. “REDD offers us the chance to put a monetary value on standing forests, and could give developing countries a way to contribute more substantially to the goals of global emissions reduction, while at the same time protecting their forest resources and investing in forest-related sustainable development for their forest-dependent communities.

Tracy Johns |

While REDD has attracted a lot of interest among policymakers, environmentalists, indigenous rights’ groups, and the investment community, Johns says that implementation still faces a number of challenges including the “readiness” of developing countries and the commitment of developed governments.

“Many of the developing countries most likely to join a REDD regime currently have limited capacity to monitor and account for changes in deforestation rates and emissions, and many also do not have processes in place to support a participatory process that will incorporate the many stakeholders impacted by a REDD program,” she said. “Creating the infrastructure to support REDD programs long-term and to address the rights and roles of all relevant stakeholders impacted by a REDD program is a huge challenge, and can only be met through significant commitments by both developed and developing countries; developed countries must provide financial support, technology transfer, and knowledge and experience transfer, while developing countries will need to commit through sustained political will to address issues of land tenure and traditional rights, as well as incorporate REDD into long-term planning.”

Johns is one of a number of WHRC researchers working on REDD. Daniel Nepstad, a tropical forest ecologist who leads the Center’s Amazon program, has been examining the potential for REDD in the Brazilian Amazon, while Josef Kellndorfer, a geographic information systems (GIS) specialist, has been working on the monitoring capacities of remote sensing technologies. Both have previously conducted interviews with mongabay.com.

AN INTERVIEW WITH TRACY JOHNS

Mongabay: What is your role at the Woods Hole Research Institute?

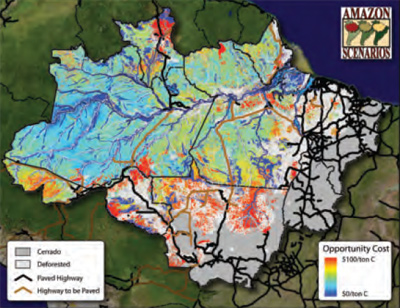

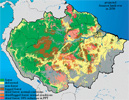

Net opportunity cost of forest protection in the Brazilian Amazon. Calculated as maximum net present value of soy or cattle production minus NPV of timber. The value was then divided by forest carbon stocks. Red represents high opportunity costs for foregoing land-use activities. Courtesy of WHRC and appearing at How much would it cost to end Amazon deforestation? |

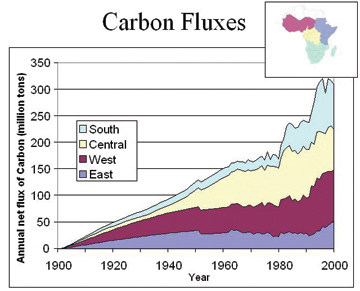

Tracy Johns: I am a Policy Advisor and Research Associate at WHRC. My role is to work with our scientific staff to link our scientific work on climate change, land use, and deforestation with relevant domestic and international policy processes. In the context of the UNFCCC we bring our scientific and economic expertise to support developing countries with the design of policies and activities to reduce emissions from deforestation and forest degradation. I work with scientists from our Africa and Amazon programs to combine our scientific efforts with capacity building in these regions and also to support the development of sound regional and national policies on forests and climate. Additionally I work with other NGO partners to provide input and support for strong federal climate policy in the U.S. that also supports reduction of emissions from deforestation and forest degradation in developing countries.

Mongabay: What is your background?

Tracy Johns: I studied biology in my undergraduate degree, and my master’s work was in forest ecology and environmental policy.

Mongabay: How did you become interested in forestry policy issues?

Tracy Johns: During my master’s degree work, I became interested in the intersection of science and policy — how science impacts and interacts with policy processes. The UNFCCC is perhaps one of the best examples of an international political process that relies on science to frame and guide its work; and within the UNFCCC, forests and land use are among the more science-driven issues. I saw this intersection as a way to pursue both my interest in forest ecology and policy.

Mongabay: Do you have any advice for a student wanting to pursue a career in forest-related policy?

Tracy Johns: I think that it is a big advantage for a student if she/he can gain technical proficiency in the science that drives and supports sound forest policy and forest management – forest ecological processes, the terrestrial carbon cycle, and also in key policy areas such as ecosystem services, land tenure issues, and economic drivers of land use change. Additionally, an internship that will provide exposure to forest policy is one of the best ways to get an idea of the opportunities for a future career.

REDD

Mongabay: What do you see as the biggest policy issues in REDD discussions?

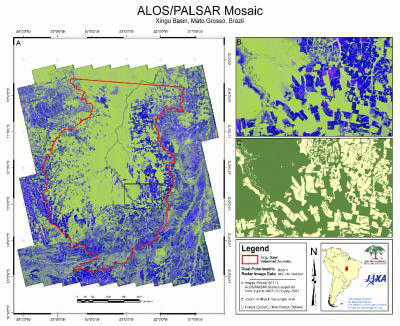

Scientists at the Woods Hole Research Center are actively involved in the development of policy mechanisms focused on compensating rainforest nations for slowing deforestation, thereby reducing their emissions from heat-trapping greenhouse gases. As part of this effort, Dr. Josef Kellndorfer and his colleagues are investigating the latest spaceborne remote sensing technologies for monitoring tropical deforestation, including a new Japanese radar sensor, the Phased Array L-Band Synthetic Aperture Radar (PALSAR), carried on board the Advanced Land Observing Satellite. Using data from the ALOS/PALSAR. Credit: Josef Kellndorfer/Wayne Walker, The Woods Hole Research Center (whrc.org) |

Tracy Johns: Countries are debating the potential role of sub-national activities and whether and how they should be included in REDD as a stepping stone to national level programs. Additionally, the issue of financing looms in the discussions. Many countries support the use of market mechanisms to fund REDD activities, while others propose the use of voluntary funds. Options such as committing a portion of proceeds from emissions trading to fund REDD activities are also under discussion.

Additionally the issue of indigenous and forest community rights has surfaced as a major topic in the REDD debate. A well-designed REDD framework could support the recognition of the role of indigenous peoples and forest communities in forest protection, but this goal must be incorporated in the design of national REDD programs, to insure that REDD does not provide an incentive to bypass the rights of these traditional forest stewards.

Mongabay: What’s holding REDD back?

Tracy Johns: One of the first challenges that may limit opportunities for REDD implementation is the level of “readiness” in developing countries to establish transparent, equitable programs to implement and monitor REDD activities. Many of the developing countries most likely to join a REDD regime currently have limited capacity to monitor and account for changes in deforestation rates and emissions, and many also do not have processes in place to support a participatory process that will incorporate the many stakeholders impacted by a REDD program. While issues of monitoring and accounting can be more readily addressed through increased financing and capacity building, creating the infrastructure to support REDD programs long-term and to address the rights and roles of all relevant stakeholders impacted by a REDD program is a huge challenge, and can only be met through significant commitments by both developed and developing countries; developed countries must provide financial support, technology transfer, and knowledge and experience transfer, while developing countries will need to commit through sustained political will to address issues of land tenure and traditional rights, as well as incorporate REDD into long-term planning.

Mongabay: What’s your outlook for REDD? When are we likely to see REDD credits in established (i.e. non-voluntary) markets?

Carbon fluxes from Africa, 1900-2000 |

Tracy Johns: Despite the many challenges that still lie before us, my outlook for REDD is optimistic. Scientific understanding of the role of tropical forests in climate change has greatly improved, as well as the technical capacity to monitor forests remotely. There is a common realization that success in the REDD process is vital to meeting the challenge of climate change. REDD has the potential to significantly reduce global emissions, to protect biodiversity and water and soil resources, to drive progress in land tenure issues and protect the rights of indigenous and forest communities, and to reduce the overall cost of meeting the climate change challenge. We simply cannot miss this opportunity, and I believe there is growing recognition of the absolute imperative to include REDD in our global strategy to avoid dangerous climate change.

Mongabay: Do you see REDD clearing a path for other ecosystem payments like water?

Tracy Johns: The lessons we learn in the REDD process have great potential to transfer to future initiatives such as designing market mechanisms to value and protect resources like water. The REDD process is already breaking new ground, and the more familiarity that stakeholders gain with these concepts, and the more experience gained in designing and implementing them, the better we will become as a community at designing innovative approaches to value other important ecosystem services.

Mongabay: Are you hopeful that REDD can be implemented on the kind of scale that would be needed to save tropical forests? Will REDD alone offer the kind of returns that will make it viable relative to other forms of land use?

Tracy Johns: The REDD process offers the potential to significantly reduce global emissions and protect tropical forests. What makes REDD different is the potential link to the resources of the carbon market. Past efforts to save tropical forests have relied on voluntary funding, and this simply has not been enough to properly value all of the benefits tropical forest provide, or to make their protection a competitive option compared to their destruction. REDD offers us the chance to put a monetary value on standing forests, and could give developing countries a way to contribute more substantially to the goals of global emissions reduction, while at the same time protecting their forest resources and investing in forest-related sustainable development for their forest-dependent communities.

Woods Hole Research Center

Related articles and interviews

|

U.S. climate policy could help save rainforests

(5/14/2008) U.S. policy measures to fight global warming could help protect disappearing rainforests, says the founding partner of an “avoided deforestation” policy group. In an interview with mongabay.com, Jeff Horowitz of the Berkeley-based Avoided Deforestation Partners argues that U.S. policy initiatives could serve as a catalyst for the emergence and growth of a carbon credits market for forest conservation. REDD or Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Degradation is a proposed policy mechanism that would compensate tropical countries for safeguarding their forests. Because deforestation accounts for around a fifth of global greenhouse gas emissions, efforts to reduce deforestation can help fight climate change. Forest protection also offers ancillary benefits like the preservation of ecosystem services, biodiversity, and a homeland for indigenous people.

|

Investing to save rainforests

(4/2/2008) Last week London-based Canopy Capital, a private equity firm, announced a historic deal to preserve the rainforest of Iwokrama, a 371,000-hectare reserve in the South American country of Guyana. In exchange for funding a “significant” part of Iwokrama’s $1.2 million research and conservation program on an ongoing basis, Canopy Capital secured the right to develop value for environmental services provided by the reserve. Essentially the financial firm has bet that the services generated by a living rainforest — including rainfall generation, climate regulation, biodiversity maintenance and carbon storage — will eventually be valuable in international markets. Hylton Murray-Philipson, director of Canopy Capital, says the agreement — which returns 80 percent of the proceeds to the people of Guyana — could set the stage for an era where forest conservation is driven by the pursuit of profit rather than overt altruistic concerns.

|

Markets could save forests: An interview with Dr. Tom Lovejoy

(3/20/2008) Market mechanisms are increasingly seen as a way to address environmental problems, including tropical deforestation. In particular, compensation for ecosystem services like carbon sequestration — a concept known by the acronym REDD for “reducing emissions from deforestation and degradation” — may someday make conservation a profitable enterprise in which carbon traders are effectively saving rainforests simply by their pursuit of profit. Protecting rainforests and their resident biodiversity would be an unintentional, but happy byproduct of profit-seeking endeavors.

Why Europe torpedoed the REDD forests-for-carbon credits initiative

(3/5/2008) Reducing emissions from deforestation and forest degradation (REDD) has been widely lauded as a mechanism that could fund forest conservation and poverty alleviation efforts while fighting climate change. At the December U.N. climate meeting in Bali, delegates agreed to include REDD in future discussions on a new global warming treaty — a move that could eventually lead to the transfer of billions of dollars from industrialized countries to tropical nations for the purpose of slowing greenhouse gas emissions by reducing deforestation rates. Conservationists and scientists applauded the decision.

|

Half the Amazon rainforest will be lost within 20 years

(2/27/2008) More than half the Amazon rainforest will be damaged or destroyed within 20 years if deforestation, forest fires, and climate trends continue apace, warns a study published in Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B. Reviewing recent trends in economic, ecological and climatic processes in Amazonia, Daniel Nepstad and colleagues forecast that 55 percent of Amazon forests will be “cleared, logged, damaged by drought, or burned” in the next 20 years. The damage will release 15-26 billion tons of carbon into the atmosphere, adding to a feedback cycle that will worsen both warming and forest degradation in the region. While the projections are bleak, the authors are hopeful that emerging trends could reduce the likelihood of a near-term die-back. These include the growing concern in commodity markets on the environmental performance of ranchers and farmers; greater investment in fire control mechanisms among owners of fire-sensitive investments; emergence of a carbon market for forest-based offsets; and the establishment of protected areas in regions where development is fast-expanding.

|

Complete map of world forests to help REDD carbon trading initiative

(2/27/2008) Policymakers, conservationists and scientists have high hopes that REDD, a mechanism for compensating countries for reducing emissions from deforestation and forest degradation, will spur a massive flow of funds to tropical countries, helping preserve rainforests and delivering economic benefits to impoverished rural communities. To date, one of the biggest hurdles for the initiative has been establishing a baseline for deforestation rates — in order to compensate countries for “avoided deforestation” it first must be known how much forest the country has been losing on a historical basis. Until now, with some notable exceptions, this data was based largely on spotty satellite assessment and surveys of national forestry departments by the U.N. Food and Agricultural Organization.

Carbon trading could protect forests, reduce rural poverty

(2/26/2008) Carbon trading from avoided deforestation (REDD) credits could yield billions of dollars for tropical countries, according to analysis by mongabay.com, a leading tropical forest web site.

Reducing deforestation rates 10% could generate $13B in carbon trading under REDD

(2/25/2008) Cutting global deforestation rates 10 percent could generate up to $13.5 billion in carbon credits under a reducing emissions from deforestation (“REDD”) initiative approved at the U.N. climate talks in Bali this past December, estimate researchers writing in Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B. But the researchers caution there are still substantial obstacles to overcome before carbon-credits-for-rainforest-conservation becomes a reality.

Bali delegates agree to support forests-for-climate (REDD) plan

(12/16/2007) Delegates meeting at the U.N. climate conference in Bali agreed to include forest conservation in future discussions on a new global warming treaty, reports the Associated Press. The move could lead to the transfer of billions of dollars — in the form of carbon credits — from industrialized countries to tropical nations for the purpose of slowing greenhouse gas emissions by reducing deforestation rates. Deforestation presently accounts for roughly 20 percent of anthropogenic emissions worldwide.

Tropical forests face huge threat from industrial agriculture

(12/5/2007) With forest conversion for large-scale agriculture rapidly emerging as a leading driver of tropical deforestation, a new report from the Woods Hole Research Center (WHRC) suggests the trend is likely to continue with Brazil, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Indonesia, Peru, and Colombia containing 75 percent of the world’s forested land that is highly suitable for industrial agriculture expansion. Nevertheless the study identifies forests that may be best suited (low population density, unsuitable climate and soils) for “Reduced Emissions from Deforestation and Degradation” (REDD) initiatives which compensate countries for preserving forest lands in exchange for carbon credits.

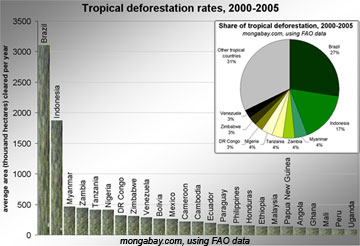

Amazon deforestation could be eliminated with carbon priced at $3

(12/4/2007) The Amazon rainforest could play a major part in reducing greenhouse gas emissions that result from deforestation, reports a new study published by scientists at the Woods Hole Research Center, the Instituto de Pesquisa Ambiental da Amazônia, and the Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais. At a carbon price of $3 per ton, protecting the Amazon for its carbon value could outweigh the opportunity costs of forgoing logging, cattle ranching, and soy expansion in the region. 2008 certified emission-reduction credits for carbon currently trade at more than $90 per ton ($25 per ton of CO2).

Returns from carbon offsets could beat palm oil in Congo DRC

(12/4/2007) A proposal to pay the Democratic of Congo (DRC) for reducing deforestation could add 15-50 percent to the amount of international aid given to the warn-torn country, reports a new study published by scientists at the Woods Hole Research Center (WHRC). The funds would help alleviate rural poverty while cutting emissions of greenhouse gases and protecting threatened biodiversity.

Could the carbon market save the Amazon rainforest?

(11/29/2007) The global carbon market could play a key role in saving the Amazon from the effects of climate change and economic development, which could otherwise trigger dramatic ecological changes, reports a new paper published in Science. The authors argue that a well-articulated plan, financed by carbon markets, could prevent the worst outcomes for the Amazon forest while generating economic benefits for the region’s inhabitants.