Photos by late Borneo rainforest hero, indigenous rights activist go online

Photos by late Borneo rainforest hero, indigenous rights activist go online

Jeremy Hance, mongabay.com

April 17, 2008

Bruno Manser Fonds releases over 10,000 photos by environmentalist hero Bruno Manser

|

|

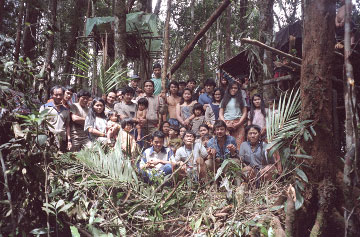

On April 19th over 10,000 of Bruno Manser’s photographs will be made available to the public on-line. The pictures are rare documentation of the nomadic Penan peoples from the Malaysian state of Sarawak in Borneo. Swiss environmentalist Bruno Manser proved an unflinching and passionate advocate for the Penans in the 1990s as their territory was increasingly deforested by industrial logging companies.

Lukas Straumann, Director of the Bruno Manser Fonds, believes the photos to be an important legacy for Bruno Manser work. “They document the culture of South East Asia’s last hunter-gatherers in a crucial moment when their culture came under pressure through large-scale systematic destruction of their ecosystem,” Starumann told Mongabay.com, adding that “apart from their socio-cultural value, the pictures could also become important evidence in land rights litigations for Penan communities who struggle to have their land rights legally recognized by the courts.”

The non-profit organization, Bruno Manser Fonds, based in Basel, Switzerland, has spent three years preserving, digitalizing, and inventorying Manser’s massive collection of photographs. The photographs will be available through the Bruno Manser Fonds website: www.bmf.ch/en.

The life of Bruno Manser

|

Bruno Manser lived among the Penan peoples from 1984-1990, during this time he became intimately aware with their struggles. Deforestation was rampant in Borneo, destroying the rainforest along with the livelihood of the Penan people.

Manser tried several non-violent means to make Malaysia and the developed world aware of the plight of the Penan people and Borneo’s rainforest. He organized peaceful blockades of logging roads in Sarawak with the Penan people. In 1999, using a hang glider, he landed on the Chief Minister Tan Sri Abdul Taib Mahmud’s lawn in Kuching. He offered the minister a truce if the Malaysian government would set a biosphere around the Penan people’s territory. He offer was denied. In Switzerland he went on a sixty-day hunger strike before Berne’s Swiss federal parliament building in an effort to press the Swiss government to ban tropical timber. Fifteen years later, the Swiss have not adopted the ban.

Such actions made him the most wanted person in the state of Sarawak. Manser was further declared ‘persona non grata’ in Malaysia; reports of a bounty on his head of up to $40,000 circulated. Despite this, he returned numerous times to the Penan people. He disappeared on his last trip in 2000. His body was never found, and in 2005 he was declared missing and presumed dead. Allegations have been made that he was murdered by loggers or the Malaysian government, but no evidence has surfaced.

“Bruno Manser dedicated his life to saving the unique rainforests of Borneo as basis of livelihood of the Penan and as a heritage of mankind,” Straumann says. “He was key to making the Penan’s struggle for the conservation of their forests known on an international level. He is also an important example of how much impact one individual can have in environmental matters.”

The Penan people today and their future

|

Despite Manser’s efforts, deforestation continued in Borneo and the Penan people were increasingly forced to abandon traditions and lead more settled lives. Without the forest that provided them with everything, they could not survive the way their ancestors had. Currently only 200 Penans, out of some 10,000, live nomadically.

A large blow occurred recently to the Penans when longtime anti-logging activist and chieftain, Keleasu Naan, was found dead. Broken bones on the body led the Penans to believe he was murdered. Under pressure local police have announced that they will exhume Naan’s body to determine his cause of death. Meanwhile, Naan’s son, Nick Keleasu, has stated that he was offered $8,000 dollars by a timber company to retract a statement he made in which he said he believed “foul play” was involved in his father’s death.

Despite such setbacks—and the continuing destruction of the forest—Lukas Straumann is not without hope. He believes that some of the decade’s worth of damage can be undone: “We should not forget that some of the secondary forests, which were logged in the 1980s, have regenerated and can still play an important cultural and environemental role.” He also sees new possibilities in the photos to reach-out to Malaysians and Southeast Asia in general. “I think these pictures will help raise global awareness on the Penan’s struggle and their yet unresolved problems. The power of images can hardly be overestimated. By making them public on the internet, we also want to enable the Southeast Asian public to get access to them. The electronic media are in a position to break the monopoly of the Malaysian, and in particular the Sarawak print media, many of which are controlled or influenced by the timber industry.”

|

Developed countries can be a strong advocate for the forests of Borneo, if they step-up. Straumann explains that currently “the European Union is negotiating a “Voluntary Partnership Agreement” on timber trade issues with Malaysia. European Citizens can pressure their governments not to relent to the lobbying of the Malaysian timber industry, which, on a worldwide scale, is playing a leading role in the destruction of the World’s tropical forests – not only in Malaysia, but also in countries like Gabon, Guyana, Papua New Guinea.” Recently, a Malaysian company was stopped from deforesting 70% of Woodlark Island in Papua New Guinea for palm oil plantations because the plan was protested heavily by islanders and internationals.

In addition, Straumann says “people can write to banks such as HSBC, Credit Suisse and Macquarie Securities to stop their cooperation with Samling Global Ltd”. Samling Global Ltd possesses the largest territory of Penan lands. Straumann says that the corporation “has gained immense profits from the Penan’s forests and is continuing to encroach on their native lands”. Concerned citizens should also contact the French Hotel Group Accor to “stop their cooperation with Interhill in the Novotel Interhill hotel project in Sarawak’s capital Kuching.” Straumann describes Interhill as “one of the worst logging companies operating on Penan lands…[which] are now reinvesting their profits from the Penan’s forests in a big hotel project.”

In 1984 when Manser went to Sarawak, 45% of its forest remained. Today, the figure is less than 10%. “In an overall view, things have clearly become worse for the Penan people,” Straumann told Mongabay. “After some ninety percent of Sarawak’s forests have been logged, plantation projects, in particular for oil palm, and new hydropower schemes are new threats to the Penan’s livelihood.”

The combination of unrelenting deforestation and new rising threats to the region, creates a situation that probably would’ve spurred Bruno Manser into some daring action. As it stands, if the situation on the ground doesn’t change, his photos may be the best evidence of the lives the Penan peoples once possessed and the forest that used to be.