Investing to save rainforests

Investing to save rainforests:

An interview with Hylton Murray-Philipson of Canopy Capital

Rhett A. Butler, mongabay.com

April 2, 2008

Profit-seeking capitalists to save rainforests?

|

|

Last week London-based Canopy Capital, a private equity firm, announced a historic deal to preserve the rainforest of Iwokrama, a 371,000-hectare reserve in the South American country of Guyana. In exchange for funding a “significant” part of Iwokrama’s $1.2 million research and conservation program on an ongoing basis, Canopy Capital secured the right to develop value for environmental services provided by the reserve. Essentially the financial firm has bet that the services generated by a living rainforest — including rainfall generation, climate regulation, biodiversity maintenance and carbon storage — will eventually be valuable in international markets.

Hylton Murray-Philipson, director of Canopy Capital, says the agreement — which returns 80 percent of the proceeds to the people of Guyana — could set the stage for an era where forest conservation is driven by the pursuit of profit rather than overt altruistic concerns.

Hylton Murray-Philipson, founding director of Canopy Capital |

“Conservation efforts over the past two decades have basically failed to deliver for the Amazon. I’ve been reading my entire adult life about the destruction of the Amazon rainforest, yet it’s still happening. What’s the problem? Frankly, lack of money. Philanthropy is too small, governments are too slow, so it’s going to be up to the market,” he told mongabay.com during a phone interview. “The only way we are going to turn this thing around is through a profit motive. This is what is needed to harness the power of markets. But it doesn’t stop with making a profit — we are also going to have to deliver a better living for local people. We need to start valuing the intrinsic parts of the forest as an intact entity rather than having to convert it for something else.”

Murray-Philipson believe the market will soon see the development of an entirely new class of financial products tied to the value of ecosystem services provided by forests. He suggests that a weighted index based on the properties of global forests could someday help fund managers determine the economic value of a given forest anywhere the world as well as provide incentives for conservation.

“The index would include blocks of forest all over the world and be based on an established set of criteria that would apply to all forests,” he explained. “For example, say you have ten different elements and each element can score 10 for a maximum score of 100. If the forest is preserving an indigenous culture, that would be one element. Others might include degree of threat, the presence endemic or endangered species, the potential for eco-tourism or sustainable harvesting of forest products, whether the forest is a corridor for biodiversity migration or rainfall generation, quality of governance, and whether local people benefit from the conservation arrangement. The index would incorporate all of the characteristics to create a yardstick by which forests around the world could be measured to give a degree of uniformity for the investor and also maintain the diversity within the asset class, which is of course the great characteristic of the forest.”

The Iwokrama Reserve, Guyana – view from Turtle Mountain |

“An advantage to the rating system is that it could promote the development of new reserves and conservation areas. For example, if you are a twenty-something year old with a love for nature and a sharp mind it would become worth your while to go to a difficult part of the world to try to “improve” a forest area by forming relationships with local beneficiaries to bring them on board, stopping illegal logging, and conducting a biodiversity survey. These actions would basically up your score in the weighting system, thereby making the forest more valuable. It’s a way of harnessing the profit motive to actually get things done. The index makes it easy for the fund manager to buy into this market.”

Over the course of two phone interviews with mongabay.com, Murray-Philipson discussed the Iwokrama deal [Private equity firm buys rights to ecosystem services of Guyana rainforest] and his outlook for payments for ecosystem services.

An interview with Hylton Murray-Philipson

Mongabay: How’s the response been to the announcement of the deal in Iwokrama?

Hylton Murray-Philipson: It’s absolutely endless. The interest is quite extraordinary.

Mongabay: What was your motivation for the Guyana deal?

Hylton Murray-Philipson: My motivation for doing any deal anywhere comes from my perception of where we are in the world. I feel we are at a crossroads. I think this is the last moment we have as a species to take remedial action before we are very soon on a path that is committed to significant climate change.

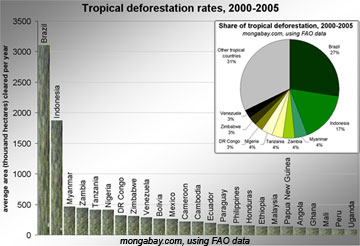

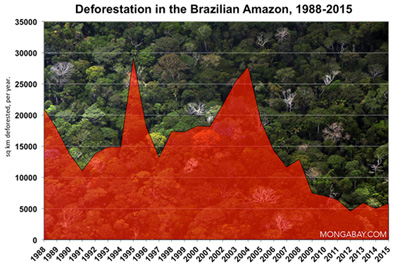

Deforestation in the Brazilian Amazon |

Looking at rainforests specifically, conservation efforts over the past two decades have basically failed to deliver for the Amazon. I’ve been reading my entire adult life about the destruction of the Amazon rainforest, yet it’s still happening. What’s the problem? Frankly, lack of money. Philanthropy is too small, governments are too slow, so it’s going to be up to the market. Our firm is bringing capital to the canopy. The only way we are going to turn this thing around is through a profit motive. This is what is needed to harness the power of markets. But it doesn’t stop with making a profit — we are also going to have to deliver a better living for local people. We need to start valuing the intrinsic parts of the forest as an intact entity rather than having to convert it for something else.

Mongabay: Why Guyana?

Hylton Murray-Philipson: I originally tried to do something in Brazil. I lived there for 5 years when I setting up an investment bank 20 years ago. I know my way around, speak the language and obviously I know that even if we won the battles in the Guyanas, Colombia, Peru, Ecuador, Bolivia, Venezuela, and we lose Brazil, essentially we lose the war. So I started out in Brazil, but the Brazilian perspective on this is very complicated. Yes, Brazil has come a long way — just two years ago they were vetoing essentially all the international debate about forests and to talk about things about forests was just not on — but even now the country is not embracing market-based solutions. They tried to do government to government payments — which didn’t win wide support — before floating their own idea of what market based solutions are, but to be honest, these don’t respond to any market that I know. At the end of the day, the lack of sort of legal definitions at the federal level makes it very difficult.

So when I came across Iwokrama in Guyana I thought, this is the answer to all my prayers — it’s really a jewel in the crown. In Guyana we have the head of state, President Bharrat Jagdeo, openly saying, “Hey guys, please come and help me because I’m at a very interesting point in my country’s development.” Guyana was a complete financial basket-case in terms of spending 94 percent of government income on debt service, but now the debt has been written off and the country is wondering where it goes from here. Guyana is also not on the forefront of destruction — it’s not like trying to go into Para or Mato Grosso. My feeling is if you can’t save the low-hanging fruit, what are you going to be able to do anywhere?

When you engage people in these issues and they say “OK fine, I agree with your perspective, but now what will I invest in?” you quickly find there’s nothing you can invest in. Moving in and buying up chunks of land in these countries is the immediate reaction people tend to have but this isn’t the answer — there’s not enough money and it’s politically, socially, and morally very unacceptable.

Iwokrama |

Iwokrama presents a special opportunity. In 1996 by act of Parliament the people of Guyana gave 371,000 hectares to be administered on their behalf and the behalf of the wider world by the Commonwealth. So we have already had 12 years of governance, which is key to ensuring that money is going to be handled properly. Typically once you do identify a place for investment, you run into the questions like: “What’s going to happen to the money if I do invest? Is it going to get recycled to Switzerland? Is it really going to make the difference on the ground that I would really like it to? In other words, am I really going to get what I think I’m going to be paying for?” Maybe I’m a cynic by looking at the precedent from the Pilot Program to Conserve the Brazilian Rain Forest funded by the G7 (PPG7) in Brazil — frankly most of that money never left Brasilia. It’s quite easy to come up with aspirational statements saying you are going to this, that, and the other, but to really make a difference on the ground is very difficult.

In Iwokrama you have the head of state who’s supportive, you have 12 years international governance, you have the partnership with the Commonwealth, you have the patronage of the Prince of Wales, you have the English language, you have the rule of law, and you’ve got a country basically half way between Brazil and the United States that has very dense, very rich, and very beautiful forests. If you can’t make something work in Guyana, I’m not sure you are going to ever make it work anywhere. So that’s a long-winded way of saying why it has to be Guyana.

Mongabay: Where do you see the market going? Do you expect it to move beyond carbon to value other ecosystem services like water?

Hylton Murray-Philipson: There are different ways of looking at ecosystem services. You could, for example, split up the water rights and sell them to Cargill, soy growers in Mato Grosso, residents of Lima (Peru) and whomever else is benefiting from the water generated by the Amazon rainforest. The water company in Sao Paulo or Georgia would be classic examples. Let me explain. There have been very powerful studies that link the Amazon rainforest to precipitation in North America, so the case can be made that the forest of Guyana plays a key economic role in the U.S. Similarly, last year Argentina saw power shortages and drought because rainfall from the Amazon didn’t make it as far down as usual. Meanwhile Brazil has $58 billion in agricultural exports last year and roughly 70 percent of the country’s electricity generation came from hydroelectric. If you don’t have rain, it directly affects power and agricultural production, essential components of the economy. Another way of looking at it is to compare rainforests to a giant utility — if you do not pay your utility bill, your power and water are going to get cut off.

However the real value of ecosystem services is in everything is bundled together. It is the sheer complexity and diversity of life that gives forests their value. So yes, I think we are moving beyond carbon. Of course, carbon is not incidental. In Guyana you do lock up upwards of 100 tons of carbon — possibly even double that or more — per hectare.

Mongabay: Beyond the entities you mention, who else will pay for these environmental services? Do you see the insurance industry as a potential customer? Where do governments of industrialized countries fit into the equation?

Hylton Murray-Philipson: Insurance companies may be a key part to this market since they are already dealing with weather related risks in places like Florida.

Kaieteur Falls outside the Iwokrama Reserve, Guyana |

An amazing potential contributor in my mind is National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP) under FEMA. If you are a resident of Florida and cannot get commercial insurance on your home you have the right to put that policy on Uncle Sam — the federal government. The commercial exposure of the NFIP is something around one trillion dollars of which 40 percent is in Florida alone. Now if you’re Treasury Secretary Hank Paulson and NFIP is reporting to you $400 billion of exposure in the extreme flood-prone areas in Florida, I would argue that it is fiduciarily irresponsible for the American taxpayer not to take out the only reinsurance that Hank Paulson could possibly provide: contributing to the preservation of the Amazon rainforest. So that is one way that insurance markets could pay for ecosystems services.

Insurance could also be a way through which a group of G-8 governments could get together and decide that they alone are going to lead the world in saving rainforests. They could mandate that all insurance in their markets will include some amount of money for rainforest conservation around the world. There is a fundamental equity in it. If you have a Lear jet, a big yacht, or a huge home, you’ve got more to insure and have to pay more. But your impact on the environment is also more and I think that is fair and just. If you have little then you aren’t going to pay as much. What point is it becoming a billionaire if the roof of your house falls on your head because you didn’t maintain it?

Mongabay: Are you looking at other parts of the world or are you going to focus on Guyana to make it work there first?

Hylton Murray-Philipson: I think we’re going to try to make it work in Guyana first.

I think the next thing we might get into is what I would describe as a “weighting” scheme for forests so that we can develop a real asset class to appeal to a fund manager who’s never seen a rainforest in his life but decides that rainforests are a good thing to invest in. An index is a perfect vehicle for this.

Amazon rainforest canopy in Peru. |

The index would include blocks of forest all over the world and be based on an established set of criteria that would apply to all forests. For example, say you have ten different elements and each element can score 10 for a maximum score of 100. If the forest is preserving an indigenous culture, that would be one element. Others might include degree of threat, the presence endemic or endangered species, the potential for eco-tourism or sustainable harvesting of forest products, whether the forest is a corridor for biodiversity migration or rainfall generation, quality of governance, and whether local people benefit from the conservation arrangement. The index would incorporate all of the characteristics to create a yardstick by which forests around the world could be measured to give a degree of uniformity for the investor and also maintain the diversity within the asset class, which is of course the great characteristic of the forest. Iwokrama would score pretty highly. It has indigenous people, good governance, and crucially, local beneficiary arrangements.

An advantage to the rating system is that it could promote the development of new reserves and conservation areas. For example, if you are a twenty-something year old with a love for nature and a sharp mind it would become worth your while to go to a difficult part of the world to try to “improve” a forest area by forming relationships with local beneficiaries to bring them on board, stopping illegal logging, and conducting a biodiversity survey. These actions would basically up your score in the weighting system, thereby making the forest more valuable. It’s a way of harnessing the profit motive to actually get things done. The index makes it easy for the fund manager to buy into this market.

What really brought me to this point is the idea that the economic model that we’ve inherited from the 19th century is no longer valid for the situation in which we find ourselves. I have two boys, age 7 and 11, and I worry about the world they are going to inherit. This process we’ve been doing since the Industrial Revolution — converting natural capital into manufactured capital and then financial capital — worked fine in 1900 when the world population was only 1.5 billion. But now that the population is 6.5 billion — going to 9 — and we are consuming at rates that even our grandparents would have found unimaginable, it is absolutely clear that business as usual is going to end in tears. Just read the official reports from the United Nations Ecosystems Assessment and the IPCC. So the question is why is there that gulf between knowledge and lack of action? The message is not getting through. We can’t sit around waiting for world leaders to figure this out, get together, and agree on something. We’ve just got to take the situation into our own hands, To a limited extent we are obviously we are going to need government support at the end of the day. But if we can sort of blaze a trail, show the way, and inform the process to the point of formation, that is the best thing we in the private sector can do right now. That is the reason behind Canopy Capital.

Mongabay: So you do believe this will be a policy-driven market to some extent?

Hylton Murray-Philipson: At some stage I believe some sort of global agreement the recognizes the importance of rainforests will have to take comes into force. I don’t think this will be the Kyoto Process which is emissions-based. We will need to move beyond emissions-based thinking.

The thinking behind this investment is that the world is eventually going to understand the value of forests in ensuring rainfall, housing biodiversity, and fighting climate change. If we see $20 per hectare per year in compensation for Iwokrama, its inhabitants, the Makushi tribe, as well as the people of Guyana would benefit. Our firm would also make a profit but 80 percent of the increase in value would accrue to the inhabitants of the reserve.

Mongabay: Your tag line is “driving capital to the canopy” — can you elaborate on your investment philosophy?

Hylton Murray-Philipson: I called the company Canopy Capital because I didn’t want to have anything to do with carbon — this is really not about carbon, it is about life. How do you put a price on life?

|

I personally regret that we have to do this but given that we are like locusts — consuming everything in our paths — we have to start putting a value on forests because otherwise, as President Jagdeo says, “they will get converted for something that will enable me or my successors to deliver the health, education, water, and electricity to the people of Guyana,” which is their right and aspiration. There’s no way we can sit in California or London and say to these guys in the developing world “protect your forests” while we enjoy a nice life. It’s not equitable and it’s not going to happen. So the only way that these forests are going to continue to exist and make a contribution to humanity at large is if we recognize their value through markets. There is a slight feeling of regret in my heart but I think it’s the right thing to do and also the best thing to do.

Money is the the means to an end, not the end itself. I feel we’ve lost our way in a world in which over 50% of people live in cities, cut off from nature.