Tuna may go the way of cod: a collapsed fishery

Tuna may go the way of cod: a collapsed fishery

mongabay.com

February 18, 2008

The collapse of the cod fishery could provide important lessons to prevent a similar fate for some tuna populations, say researchers presenting at the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS) Annual Meeting in Boston on February 18.

Overfishing a fast-driving depletion of some tuna stocks. For example, landed value of yellowfin tuna in the Western Central Pacific Ocean was US$1.9 billion in 2001, but US$1.1 billion in 2004. The trends are similar to those seen for code in the Canadian Atlantic where the value of catch fell from $1.4 billion in 1968 to $10 million in 2004.

“Conventional fisheries wisdom did not work for the northwest Atlantic cod and is now failing for tuna in some cases,” said WWF’s Katharine Newman, moderator for the panel. “We need to find solutions that advocate sustainable fishing starting right at the source like the Coral Triangle down to consumers’ plates through Marine Stewardship Council [MSC] certification and public awareness.”

The researchers note that despite a decade of conservation measures, cod populations have not recovered as fisheries scientists predicted they would.

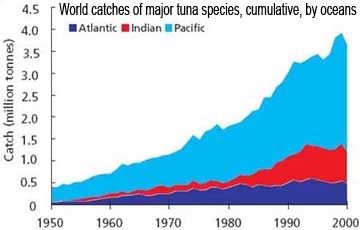

World catches of major tuna species, cumulative, by oceans, 1950-2000. Graph courtesy of FAO. |

“Does the fault lie in the fishermen, the regulators, or the scientists” Or is the answer to be found in history?”” asked author Mark Kurlansky.

“Although we know much about Atlantic cod and bluefin tuna, we have not learned a thing from their history and we may lose them because of that,” said University of British Columbia’s Daniel Pauly.

The researchers said that by examining the plight of cod and learning more about tuna, they can improve management of tuna fisheries. For example, Jose Ingles of WWF-Philippines said that fish aggregating devices are causing significant juvenile bycatch, threatening species like bigeye and yellowfin tunas.

“This hurts the economy and impacts the species,” said Ingles. “If juvenile fish are allowed to mature, they would be worth more than $1.5 billion annually—significantly higher than the $236 million currently derived from juvenile catch.”

Barbara Block, a marine biologist at Stanford University’s Hopkins Marine Station, says that tagging of tuna has revealed important insight on the life history of tuna. For example, bluefin tuna spawn at age 12, not age 8. Harvesting fish that have yet to breed is a sure fire way to contribute to population depletion.

“For the past two decades, we’ve been lowering the age for a commercial mature fish to increase supply, and yet our tagging data has demonstrated the Gulf of Mexico bluefin need more time, without pressure, to breed,” said Block. “You’ve got to keep a lot of bluefin in the bank in order to get the interest.”

“The overly generous commission quotas mean that each year fishing fleets are cutting more deeply into the principal: the breeding population of bluefin,” explained a news release from Stanford. “The cumulative effect of annual overfishing throughout the North Atlantic has sent the number of natives plummeting.”

Rashid Sumaila of the University of British Columbia says that “new joint management between juvenile and adult yellowfin and bigeye tuna catching nations” could enhance the tuna catch while reducing pressure on stocks.

“This approach could have prevented the depletion of cod stocks off Newfoundland and such balancing can reduce the chance of a similar fate befalling tuna stocks of the Coral Triangle,” he said, while warning “This panel discussion can only flag the very real danger that tuna populations face. What we need is to use all the diverse lessons we have learned from cod and galvanize global action for the fast-disappearing tuna.”