- In mid-January, Mongabay learned that the government of Papua New Guinea had changed its mind: it would no longer allow Vitroplant Ltd. to deforest 70% of Woodlark Island for palm oil plantations.

- This change came about after one hundred Woodlark Islanders (out of a population of 6,000) traveled to Alotau, the capital of Milne Bay Province, to deliver a protest letter to the local government; after several articles in Mongabay and Pacific Magazine highlighted the plight of the island; after Eco-Internet held a campaign in which approximately three thousand individuals worldwide sent nearly 50,000 letters to local officials; and after an article appeared in the London Telegraph stating that due to deforestation on New Britain Island and planned deforestation on Woodlark Island, Papua New Guinea had gone from being an eco-hero to an ‘eco-zero’.

How Woodlark Island’s plight went from local to global

In mid-January, Mongabay learned that the government of Papua New Guinea had changed its mind: it would no longer allow Vitroplant Ltd. to deforest 70% of Woodlark Island for palm oil plantations. This change came about after one hundred Woodlark Islanders (out of a population of 6,000) traveled to Alotau, the capital of Milne Bay Province, to deliver a protest letter to the local government; after several articles in Mongabay and Pacific Magazine highlighted the plight of the island; after Eco-Internet held a campaign in which approximately three thousand individuals worldwide sent nearly 50,000 letters to local officials; and after an article appeared in the London Telegraph stating that due to deforestation on New Britain Island and planned deforestation on Woodlark Island, Papua New Guinea had gone from being an eco-hero to an ‘eco-zero’.

The endemic Woodlark Cuscus is safe for now. Photo by Tim Flannery |

Except for the article in the London Telegraph, the issue of Woodlark Island was largely ignored by mainstream western media. For many involved this was disappointing, since the plight of Woodlark Island so perfectly presented the wholesale destruction palm oil plantations have been causing in Asian and Pacific forests for years. Dr. Glen Barry, founder and director of Ecological Internet, referred to the situation as the “epitome of ecological evil” since this “incredibly diverse island would be turned over to a monoculture crop”. Although the issue barely touched mainstream media, it still found its way from local protestors to scientists to global organizations, eventually putting international pressure on the decision-makers.

Mongabay first learned of the plight of Woodlark Island from a blog entry by the conservation organization EDGE (Evolutionary Distinct and Globally Endangered). The organization had been contacted by researchers on the ground. After receiving help and information from Alexander Rheeney, an environmental journalist who covered the issue locally, Mongabay sent word to various campaign organizations. Dr. Barry’s Ecological Internet took it on, setting up the campaign to flood Papua New Guinea’s government with e-mails from around. In the meantime, island natives continued to pressure the government and the London Telegraph picked up the story. It appears that the combined protests and negative attention were enough to sway the government to drop the project.

Opposition in many forms

There can be no doubt that the most important part of the opposition to the deforestation of Woodlark Island was the courageous citizens of Woodlark themselves, who decided not to allow the government and Vitroplant Ltd. to devastate the island’s ecology, resources, and way of life for short-term monetary gain. Mongabay had been in contact with one of the leaders of the local opposition, Dr. Simon Piwuyes, from early on. He had this to say when the government pulled the project: “This is fantastic. It is important that the livelihood of the Woodlark Islanders and the eco-system that surrounds them is maintained. Woodlark Islanders live care-free lives in the midst of the ocean and their rich forest land. The forest and the animals play an irreplaceable importance in the lives of the islanders. It is a great relief to learn that the government has spared rare species that our earth desperately loves to keep. I, on behalf of the Woodlark Islanders, salute the government for the decision.” When asked why he thought the government changed its position, Dr. Piyuwes stated: “Number one: pressure from the landowners, number two: pressure from the NGOs, and number three: pressure from international organizations and individuals”. He added, “On this note I salute all organizations and individuals for signing up for this great issue. Our earth needs such cooperation.”

The cooperative efforts also included scientists and researchers. Dr. Kristofer Helgen, a mammalogist who focuses on species in the Papua New Guinea and its neighboring islands, stated, “I think that this is very good news. Woodlark Islanders loudly objected to major oil palm development on Woodlark. Their campaign to prevent this action involved contacting international researchers to attract attention to their cause, which is how I came to be aware of the situation.” Researchers and scientists proved instrumental in spreading the word and providing continual context and information. Without them the issue would never have made it to a variety of media sources.

Forests.org, part of Ecological Internet, was the largest organization to take on the issue. Ecological Internet asks online members to send out protest letters regarding various environmental issues. When asked why he decided to set-up a campaign for Woodlark Island, Dr. Barry expressed a personal link to the region: “[Ecological Internet’s] efforts began with Papua New Guinea. The country is near and dear to my heart. I married a woman from Papua New Guinea, and my wife and daughter are there visiting now.” Dr. Barry also felt positive about his organization’s ability to make a difference in this situation. “I was quite confident,” he says, “given the secrecy of this project with the shady Malaysian company that once we exposed it we could either halt the project or delay it long enough for further scrutiny and oversight”. Dr. Barry describes the power of his organization as ‘the boomerang effect’: the issue goes out to his over 100,000 members worldwide—living in almost every nation—and then boomerangs back to the local nation involved. Carly Waterman, project coordinator for EDGE, believes that the victory for Woodlark Island “really highlights the power of the Internet, where one person’s voice can turn into millions overnight”

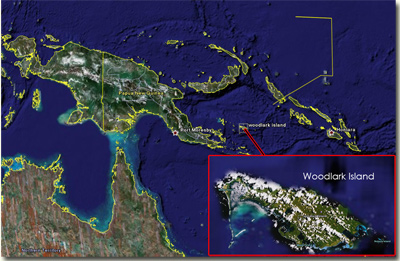

Map modified from Google Earth |

At the time of the protest by Ecological Internet there was an opportunity to remind Papua New Guinea of its previous pro-environmental statements, namely its desire to receive funds for preserving its forests to mitigate climate change. Papua New Guinea even made headlines during the Bali conference on climate change when one of its members, Kevin Conrad, had the courage to stand-up to the world’s super-power. “I would ask the United States, we ask for your leadership,” Mr. Conrad said, “but if for some reason you’re not willing to lead, leave it to the rest of us. Please get out of the way.” His comments were met with applause from leaders worldwide and shortly thereafter the U.S. caved to international pressure. The article on Woodlark Island in the London Telegraph alluded to this very moment in its observation that Papua New Guinea was not truly an ‘eco-hero’ but an ‘eco-zero’ due to its willingness t engage in deforestation. Dr. Barry also grasped the opportunity: “You were leaders of rainforest conservation, now you are going to allow an island with endemic species and people living in harmony with their rainforest to be essentially mowed down.” There is no question that the comments made during the Bali conference, and in previous arenas, came back to haunt the government of Papua New Guinea.

What the decision protects: the singularity of Woodlark Island

Papua New Guinea and its surrounding islands is a region of ecological wonders. Woodlark Island alone possesses at least twenty-four endemic animal species; the island has been only partially surveyed by biologists; each new expedition usually turns up a species unknown to science. Most famous of the endemic species is the Woodlark Cuscus, an arboreal marsupial. Islanders occasionally hunt and eat the Cuscus, but this has not affected its healthy population. If Vitroplant Ltd. had been allowed to go ahead it is quite conceivable that many of Woodlark Island’s species would have become endangered. Dr. Helgen noted that “for animal species unique to Woodlark Island, including the beautiful Woodlark Cuscus, the island’s forests are their only home. The decision not to destroy those forests is a clear victory for everyone interested in the long-term survival of all of Papua New Guinea’s unique wildlife species, which have fundamental cultural and ecological importance in this island nation of ancient and beautiful forests.” The very ecological systems of the island would have been affected as well. Dr. Dan Polhemus stated in a previous article that supplanting forest with palm oil greatly degrades local water systems. As well, it was believed that chemicals and fertilizers used on the island would end up contaminating the surrounding coast, eliminating the fish supply that islanders depend upon.

It is not only the ecology of the island that has been preserved by the government’s decision, but the islander’s unique culture as well. Deforestation of 70% of the island would have drastically changed a culture whose subsistence relies on the island’s ecology, an ecology that has been shaped by the islanders as much as the islanders have shaped it. Dr. F.H. Damon, an anthropologist who has been studying the Woodlark Island for over thirty years, says that “there remains on the island something of a unique example of a regional social and ecological system that supported human and other life for 2000 and more years.” Employing gardening, small-scale hunting, and pig-herding the islanders have built a sustainable way of life for themselves and the island’s other species within a mere 80,000 hectares (the size of New York City).

It is easy to list off what is being preserved by not developing Woodlark Island, but it’s more difficult to fully comprehend the agglomerate richness of a place like Woodlark Island in its global context. Dr. Barry describes Papua New Guinea as “one of four remaining areas of rainforest wilderness—in terms of size and contiguous intactness.” He says that “as well as Papua New Guinea, the other three areas are the Amazon, the Congo, and the Guyana Shield. Unlike Europe, China, or the United States, where all habitats are small and fragmented, it is very important not to let these last four remaining areas become fragmented.”

Still not safe: the future of palm-oil

Unfortunately such fragmentation may still occur in Papua New Guinea. Most people involved with Woodlark Island believe that the island is still not safe from palm oil plantations or other forms of destructive development. “It is very likely this issue will appear again in the near future,” Dr. Barry said, “any rainforest is never truly protected.” Dr. Damon agrees, “In the scheme of things this is a small decision amidst massive movements which may yet overwhelm the island’s ecology and culture, a culture that has been being eroded for 150 years. Yet the people of the island said no to one possible direction for their future. That is a courageous act.” Dr. Simon Piyuwes is aware of the danger. He said that while the islanders welcomed the government’s rejection of the project they stilled demanded the company’s official withdrawal. “This is because the land lease has been granted to the company,” Dr. Piyuwes explained, “we would like the lease to be nullified.” It seems the future of palm oil remains strong, even though this ‘green’ biofuel is no greener than gasoline.

A recent study of biofuels and carbon sequestering has proven that virtually all agricultural biofuels actually increase emissions that drive climate change. This report has received worldwide attention. In a comparison with various biofuel crops, palm oil proves to be the most environmentally damaging, especially as it is usually produced on cleared rainforest and peatlands. According to the study, it would have taken Woodlark Island eighty-six years for the palm oil plantations to make-up for the amount of carbon their development released in the atmosphere, and yet the lifecycle of a palm oil plantation is around thirty years, meaning that it could never overcome its carbon debt and would be a net source of CO2.

Despite these reports, scientists believe that biofuels, and in particular palm oil, will continue to threaten Papua New Guinea’s forests. Both Malaysia and Indonesia, the kings of palm oil, have felled so many forests and peatlands for the crop that few places remain for expansion, which is one reason why Papua New Guinea is suddenly under great pressure to cave into the palm oil industry. “I am sure that palm oil plantations will continue to expand in Southeast Asia and Papua New Guinea, at least as long as global demand for palm oil remains high,” says Dr. Helgen. “This demand is linked to strong interest in… ‘biofuels’ as alternative and inexpensive sources of energy, and especially by demand for biofuels in the rapidly growing economies of China and India.” In addition, Dr. Barry points out that the Prime Minister of Papua New Guinea, Michael Somare, never commented on the government’s decision to pull Vitroplant out of Woodlark Island. Barry says that Prime Minister Sumari’s “interest in logging and bad environmental record has shown him to be a hypocrite. I have seen this happen in Uganda, a minister cancels a project while the Prime Minister does not comment on it. It means that it will be likely that palm oil production and logging will be seen again in Papua New Guinea.” Dr. Damon adds a further warning for the future: “until we devise new energy sources and models of the human good, [palm oil production] is a track to destruction. Monocrop agriculture is not a viable future but so many things have to change before we have a realistic alternative that it is almost hopeless to think about a different future.”

Some scientists believe there are ways to counter the current biofuel rush. “I think that part of the solution to countering the ‘blitzkrieg’ expansion of palm oil plantations into former rainforested lands across Asia and Melanesia is getting the word out globally that the global biofuel industry,” says Dr. Helgen, “especially those parts of the industry that involve massive tropical deforestation, involve catastrophic losses of biodiversity… and may have a huge negative impact in worldwide efforts to counteract the acceleration of global climate change.” With more attention placed on biofuels by researchers and governments—the EU has already taken notice—it is possible the palm oil industry will begin to wan in South East Asia. Dr. Barry sees hope in current trends, “I think the kind of unfettered growth that we have seen in the last few years as biofuels and oil palm were heralded as climate savior is being legitimately questioned.” He adds that “as we approach 7 billion people, countries will have to choose between adequately feeding and adequately transporting themselves.” Such choices will hopefully lead to further research studies and a greater focus on more effective ways to fight climate change.

The necessity of celebrating victories

Beginnings of an oil palm plantation. Courtesy of UNEP |

While Woodlark Island is still threatened, while so much of South East Asia’s forests have succumbed to palm oil, and while every year more and more effects from climate change are seen, some might believe that claiming any victory is premature. However, Dr. Barry who has seen both victories and disappointments in his organization, says, “I don’t know how else to sustain a movement and grow a movement than celebrating positive developments.” Such celebrations, whether of preserving Woodlark Island or ending the use of rainforest wood to make New York City’s benches, are important “to sustain ourselves, and give ourselves hope… We live to fight another day.” Dr. Barry concluded that for environmentalists, “A lot of this is fighting a defensive action. When the moment comes where the world finally begins to focus on the necessity of large-scale ecological renewal the seeds of habitat will remain to make this restoration possible.”

For Dr. Piyuwes, and the inhabitants of Woodlark Island, there is no question that this is a victory. When asked what advice he would give to those participating in future struggles for conservation, he had this to say: “We need to preserve our forest from deforestation. There are other alternatives to development. There are many organizations and individuals nationally and internationally who are willing to support you on the issue of deforestation. My advice is to engage the international organization and media to battle the issue.” Dr. Piyuwes is now able to imagine a much more celebratory future for his native island than anyone could have a month ago. “Number one,” he says, “we will demand the Government to give back the land to the islanders (woodlark is state land). Number two, declare woodlark as protected land. Number three, encourage eco-tourism.” Only the victory over Vitroplant allows such happy plans to be realistic.