$1 trillion carbon market in the U.S. by 2020 says study

$1 trillion carbon market in the U.S. by 2020 says study

mongabay.com

February 14, 2008

The U.S. carbon emission trading market will top $1 trillion by 2020 if policymakers continue on their current path towards a comprehensive “cap-and-trade” program, estimates an analysis released at climate roundtable discussions at the UN General Assembly in New York. The U.S. market will be more than twice the size of the European Union’s Emissions Trading Scheme, presently the world’s largest carbon trading marketplace.

The study, published by research economists from New Carbon Finance, examined 13 climate change bills under discussion in the U.S. House of Representatives and Senate and concluded that an economy-wide cap-and-trade system for U.S. greenhouse gases would likely begin operating within four to five years.

A news release from New Carbon Finance explains how a “cap-and-trade” system world work:

-

Under a “cap-and-trade” system, the federal government would ration the amount of carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases that businesses emit by issuing them permits. A business wanting to emit more than its entitlement may buy the right to do so from a business that emits less than its entitlement. The U.S. already has cap-and-trade systems in place for sulfur oxide compounds (SOx) and nitrogen oxide compounds (NOx).

The biggest buyers of greenhouse gas emission credits will be large emitters, especially coal-burning power utilities, petroleum refiners and other heavy industries like cement manufacturers.

Democratic presidential candidates Democrats Hillary Clinton and Barack Obama along with Republican presidential candidate John McCain have called for a domestic trading emission system in the hope of reducing emissions by 60-80 percent from 1990 levels by 2050.

“Even if the current Bush administration rejects all of these bills, the next President will be less inclined to use a veto. All leading 2008 presidential candidates have endorsed the need for action and some have already supported significant emissions reductions,” said Michael Liebreich, CEO of New Energy Finance, parent of New Carbon Finance.

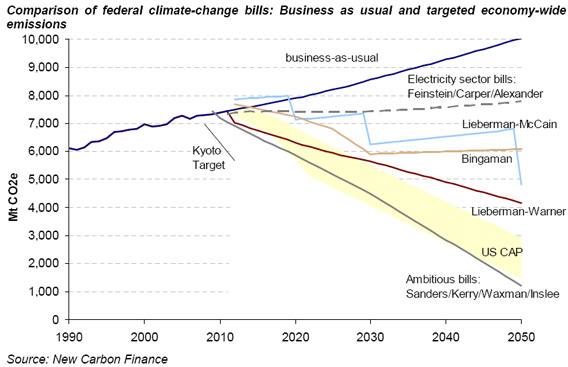

The top line (blue) illustrates how emissions might develop in the absence of any cap-and-trade programme (business-as-usual or BAU), and includes the expected impact of the recently passed Energy Bill, state Renewable Portfolio Standards (RPS) and various other policies expected to reduce emissions outside of cap-and-trade. The bills included in the low and high-demand scenarios have been grouped together since their targeted emissions reductions are very similar (dotted grey line for low-demand scenario and solid grey line for high-demand scenario). It is interesting to note that the targets suggested by the US Climate Action Partnership, an important group of multinationals and other organizations aimed at pushing the federal government for action on climate change, are more stringent (see yellow area) than the Lieberman-Warner (solid brown line).

The report notes that “bills before Congress either prohibit or severely restrict the transfer of allowances from trading systems in other parts of the world, including the EU’s Emissions Trading System (EU-ETS), and the Kyoto Protocol’s Clean Development Mechanism (CDM) and Joint Implementation (JI) schemes.” Emissions reductions in developing countries are generally cheaper to achieve than cuts in industrialized countries.

A ban on international project credits would likely drive U.S. carbon prices to $35-40 per ton as soon as 2015, estimates the report. Allowing U.S. firms to trade credits with entities abroad — including credits generated about forest conservation (REDD) schemes — would reduce prices.

“Excluding or limiting the inclusion of international project credits in any U.S. carbon cap-and-trade system will have two important consequences. For the U.S. market, it will rule out a significant source of inexpensive abatement, pushing the carbon price to unnecessary high levels. It will also remove most U.S. demand for international credits, hampering the growth of projects and technology transfer to developing countries,” said Milo Sjardin, who heads the North American division of New Carbon Finance.

“We believe that, to smooth the transition to a carbon-constrained economy, any climate change bill should provide for international project credits, currently available at $10 to $20 per tonne. This component can then be reduced over time to achieve greater emissions reductions within the U.S.”

The report forecasts the impact of various carbon prices on American consumers. Under a “cap-and-trade” system, consumers would see higher costs of electricity, gasoline, and natural gas.

New Carbon Finance says that “any bill passed by the Congress is likely to include trade sanctions on imports from countries unwilling to participate in mandatory carbon emission caps.”

“Developed nations may use this measure as a negotiating lever to put further pressure on large developing nations to reconsider their position, i.e. their ongoing refusal to consider hard reduction targets,” said Liebreich. “Although this arrangement seems to be a border tax adjustment it is possible that it can be done in a way that complies with WTO rules, provided a few conditions are met. Developing countries should bear in mind that even if they are successful in negotiating away the need to control their greenhouse gas emissions, they will likely face the impacts of climate change legislation through an indirect route, via their export trade balance, and potentially sooner than they think.”

This article uses quotes and information from a New Carbon Finance news release